“Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” in John Fogerty’s hands is a homecoming disguised as a hoedown—joyful banjo and fiddle sparkles wrapped around the wistful truth that the road always calls.

The most important thing to understand right away is that “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” wasn’t written as a “new” John Fogerty composition at all—it’s an old American song with deep roots. The song is commonly credited to Cliff Hess (who copyrighted it in 1924, sometimes under the alias Roy B. Carson) and it circulated widely under the alternate title “Blue Ridge Blues.” That history matters, because it explains why the melody feels like it was always waiting for you somewhere—like a tune you might have heard drifting from an open window long before you ever knew its name.

Fogerty’s recording enters the story at a very specific and emotionally charged moment in his career: after the whirlwind and fracture of Creedence Clearwater Revival, he reappeared under a new banner—The Blue Ridge Rangers—and “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” was the first single he released in that identity. It came out as a 45 rpm single in October 1972, backed with “Have Thine Own Way, Lord,” and—tellingly—it didn’t chart. That “non-charting” fact isn’t a failure; it’s a clue. It suggests Fogerty wasn’t chasing the mainstream moment so much as chasing a private feeling: the sound of the records that raised him, the rural harmonies and gospel-country DNA that lived underneath his rock & roll grit.

Then, in April 1973, the full album arrived: The Blue Ridge Rangers—a studio project credited to the “band” with no mention of Fogerty on the original cover, a deliberate attempt to step away from the CCR shadow. The album is made of traditional and country covers, and the most beautifully obsessive detail is this: Fogerty played all the instruments himself. “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” opens that record like a door flung wide—banjo brightness, fiddle energy, a pulse that feels half-front-porch, half-highway.

There’s something almost moving about that one-man-band choice. It’s not just a studio gimmick; it’s a statement of solitude and control—one musician building an entire little world so the feeling won’t be diluted. According to song notes, Fogerty recorded it at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, with engineering credited to Skip Shimmin and Russ Gary. You can hear that intimacy in the way the instruments sit close: the track doesn’t feel “produced” so much as assembled by hand, like a carefully carved piece of woodwork.

So what does “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” mean when Fogerty sings it?

At heart, it’s a rambling song—restless, romantic, slightly haunted. The Blue Ridge isn’t merely a mountain range; it becomes a symbol for the kind of “elsewhere” people carry inside them: the place you imagine when life feels too crowded, too complicated, too loud. The lyric’s sadness is gentle rather than tragic—more longing than despair—yet the tune keeps dancing forward, as if the body knows it must move even when the heart is looking back. That tension is the secret engine of the performance: joyful music carrying a lonely impulse.

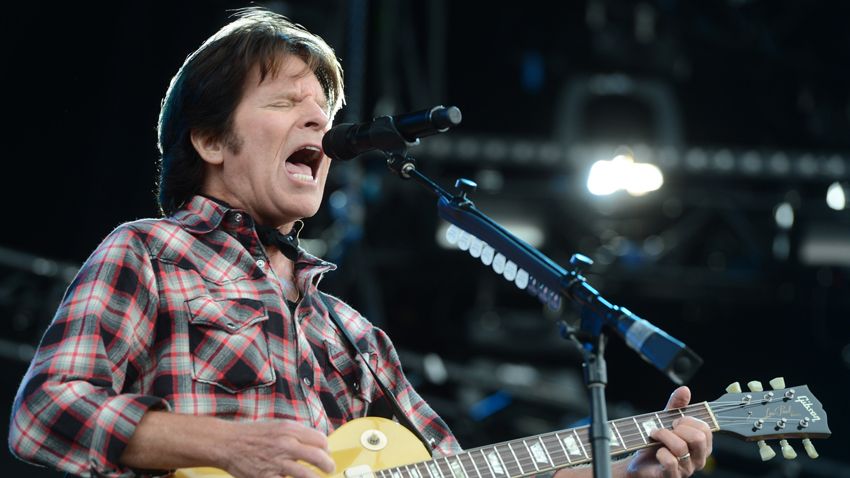

And Fogerty—who made his name singing about rivers, roads, storms, and omens—understands that instinct better than most. When he later returned to the song in concert decades on, it wasn’t nostalgia for novelty’s sake; it was a reminder that some songs don’t age—they simply deepen. Even his own archives and fan chronologies highlight how “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” kept reappearing live across years, like a tune he could step into and feel oriented again.

In the end, “Blue Ridge Mountain Blues” is Fogerty showing a different kind of strength: not the swagger of rock hits, but the humility of tradition. A man who’d already filled arenas choosing to disappear into an old folk tune—then re-emerge, smiling, with dust on his boots and light in his hands. John Fogerty doesn’t just perform the song; he restores it, and in doing so, he reminds us that the truest “blue” isn’t always heartbreak. Sometimes it’s simply the color of distance—beautiful, aching, and impossible to forget.