“Blind Hope” is the moment a dream stops being a comfort and becomes a question—how long can you survive on wishing, before you have to choose a way out?

“Blind Hope” sits quietly inside David Cassidy’s first solo album, Cherish—released in the U.S. in February 1972 on Bell Records—yet it carries a kind of emotional gravity that doesn’t need volume to be felt. It’s track 4, placed early enough to matter, as if the album wants you to understand something before the more familiar pop comforts arrive: behind the bright fame and the clean photos, there is a voice trying to speak plainly about uncertainty.

The song was written by Adam Miller, one of the key songwriters shaping the more “grown-up” mood of Cherish. The album itself was produced by Wes Farrell and recorded in 1971 at Western Recorders (Studio 2) in Hollywood—the kind of studio where Los Angeles pop could be polished to a shine. But “Blind Hope” resists shine. It doesn’t sparkle; it quietly aches.

What makes the song feel expensive—worth leaning into—is its refusal to glamorize hope. In most pop songs, hope is a bright promise, a cinematic sunrise. Here, hope is blind: not guided by proof, not supported by certainty. It’s the kind of hope people cling to when they don’t have a plan, when they’re tired of waiting for someone else to change, tired of trusting tomorrow to fix what today keeps breaking.

The lyric opens with daylight imagery—the sun is shining high—but it isn’t a cheerful beginning. It’s almost ironic, like the world looks fine from the outside while something inside feels trapped. And then the line that often hits hardest arrives with calm clarity: “We won’t get by on blind hope.” That’s the song’s spine. It’s not a romantic line, not a dramatic one—just a truth spoken quietly, the way truth often comes when you’ve run out of ways to pretend.

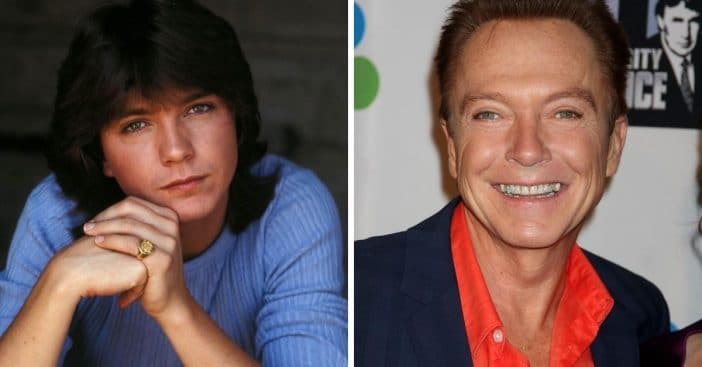

This is where Cassidy’s interpretation matters. On Cherish, he was stepping into the world as a solo singer—no longer just the familiar voice attached to a television narrative, but a young artist trying to sound like himself. “Blind Hope” gives him room to do that. He sings with restraint, not pleading for pity, not performing heartbreak like theater. His tone suggests someone sitting in a room after an argument has cooled, realizing that love can’t survive on atmosphere and wishful thinking alone. There’s a steadiness in his delivery that feels older than his years—like a person learning, for the first time, that wanting something doesn’t make it real.

And because it’s an album track rather than a major chart single, “Blind Hope” lives the way many of the most meaningful songs live: discovered privately. It’s the kind of song you find when you stop skipping, when you let the album play through, when you’re not hunting for the hit but listening for something that sounds like your own thoughts.

If you look at the emotional architecture of Cherish, “Blind Hope” is part of a thread: Adam Miller wrote multiple songs on the album, and you can feel a shared sensitivity—melancholy without melodrama, honesty without cruelty. In that context, “Blind Hope” feels like the record’s early turning point: the moment where the album admits that growing up isn’t simply about louder guitars or tougher lyrics, but about facing the fact that some situations will not improve unless you stop feeding them with fantasy.

The deeper meaning of “Blind Hope” is not pessimism. It’s responsibility. It’s the quiet understanding that hope, to be useful, needs action—needs a decision, a boundary, a step forward. Otherwise, hope becomes a lullaby you sing to yourself while your life stays the same. That’s why the song lingers: it doesn’t just describe feeling lost; it challenges the listener to notice when hope has become a habit instead of a bridge.

In the end, “Blind Hope” is David Cassidy sounding less like a star and more like a person—someone looking at a bright day and admitting that light alone won’t solve what’s broken. It’s a song that doesn’t shout for attention, but once you hear its truth, it can be hard to unhear: wishing is not living—and love can’t survive on “blind hope.”