A postcard from California’s long twilight—Dwight Yoakam sings of grit, glamour, and getting by in “The Late Great Golden State.”

Before the guitars even bite, the context matters. “The Late Great Golden State” opened Population Me—released June 24, 2003 on independent Audium/Koch—and it was issued as the album’s second single, where it reached No. 52 on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs. The cut was written not by Yoakam but by Los Angeles honky-tonk stalwart Mike Stinson, whose original appeared a year earlier on his debut; Stinson’s lyric—equal parts gallows humor and homesick pride—handed Yoakam the perfect prologue for a lean, late-career statement. A music video followed, directed by the prolific Steven Goldmann.

Yoakam places the song first on the record for a reason. As an album opener, it tells you how the next half hour will feel: sharp, unfussy, Bakersfield to the bone. The track runs a compact 2:26–2:28 and snaps like a sun-bleached billboard in a Santa Ana wind. Production is by longtime collaborator Pete Anderson—their partnership’s final studio bow—so you hear that taut Telecaster grammar and the air around the band that marked Yoakam’s best sides. The album credits also nod to the company he kept here: Timothy B. Schmit of the Eagles adds background vocals, and the arrangement leans on bright banjo figures, a color that turns Stinson’s sardonic lines into a wry street parade.

The story behind the song begins a few miles east of the charts. Stinson—then a fixture of L.A.’s neo-honky-tonk rooms—wrote “Late Great Golden State” as a cracked love letter to California: funny, fatalistic, and somehow still affectionate. When Yoakam—arguably the city’s most famous Bakersfield son—cut it for Population Me, the fit was instant. The lyric’s deadpan couplets (“I ain’t old, I’m just out of date”) mirror the mood of an artist who had stepped off major-label radio’s fast lane and was content to make records to his own standard. Stinson’s song had already earned local praise; Yoakam’s version broadcast that wit and weariness well beyond Sunset Boulevard.

Meaning? For older listeners, the chorus lands like a sigh after a long workday. It’s California as many knew it: opportunity and bluff, overflowing promise and an empty plate—sometimes in the same afternoon. Yoakam doesn’t romanticize; he testifies. The band keeps a modest lope, banjo and electric guitar trading little jabs while the vocal carries the weight. Where Stinson’s lines grumble about “one slip from a grim fate,” Yoakam delivers them with that high, lonesome clarity that refuses self-pity. It’s the sound of staying put and making do, a gumption song disguised as a throwaway quip.

From a career vantage, the single’s No. 52 peak says as much about the era as it does about the record. Yoakam had shifted to an indie label with less radio muscle, yet Population Me still charted respectably and, more importantly, preserved his aesthetic—spare arrangements, live-band torque, no syrup. It was also the closing chapter of his long studio run with Pete Anderson; within two years, Yoakam would self-produce Blame the Vain and carry this hard-edged independence into a new phase. In that light, opening the album with someone else’s hymn to California’s frayed edges feels almost like a valediction: a nod to the scene that raised him and a promise to walk forward under his own weather.

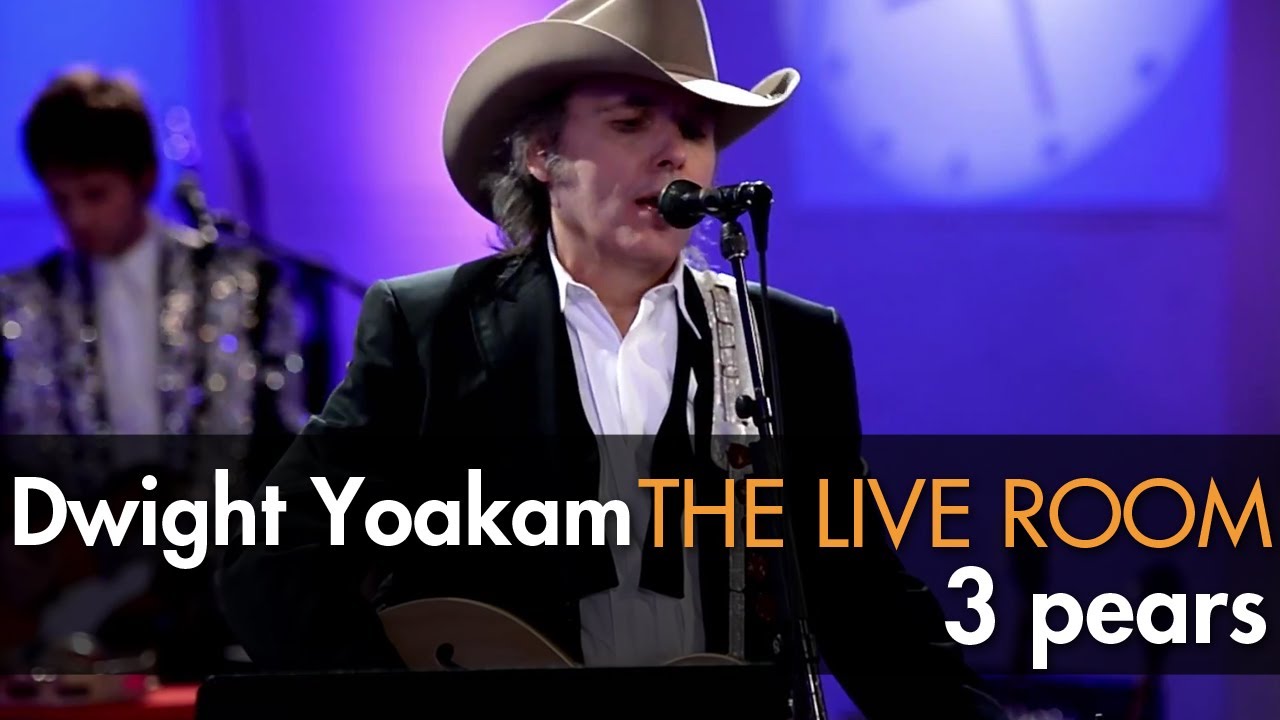

There’s some living history stitched into its release, too. The music video (directed by Steven Goldmann) caught Yoakam in trim black, the band snapping behind him—telegraphing resilience more than rage—and he took the tune to national television in 2004 with a Tonight Show performance; it made an ideal three-minute calling card for a craftsman who never needed bombast to command a room.

What sticks, years on, is the tone: tough, witty, unembarrassed by truth. “The Late Great Golden State” doesn’t eulogize California so much as level with it—like an old friend who knows your worst stories and shows up anyway. The details—Stinson’s unblinking rhyme, Anderson’s wiry guitar frame, the bright banjo clatter and Schmit’s feathered harmonies—hold the picture steady while Yoakam sings it plain. If you once drove those freeways with the window down and a dashboard radio for company, this one folds time. The sun’s a little harsher now, the rent higher, the avenues more crowded—but the rhythm under your hand on the wheel? That part hasn’t changed. Dwight Yoakam gives it back to you, three verses and a grin, like a man who’s earned the right to tell the story and still loves the place enough to stick around.