The Winding Road Between Memory and Redemption

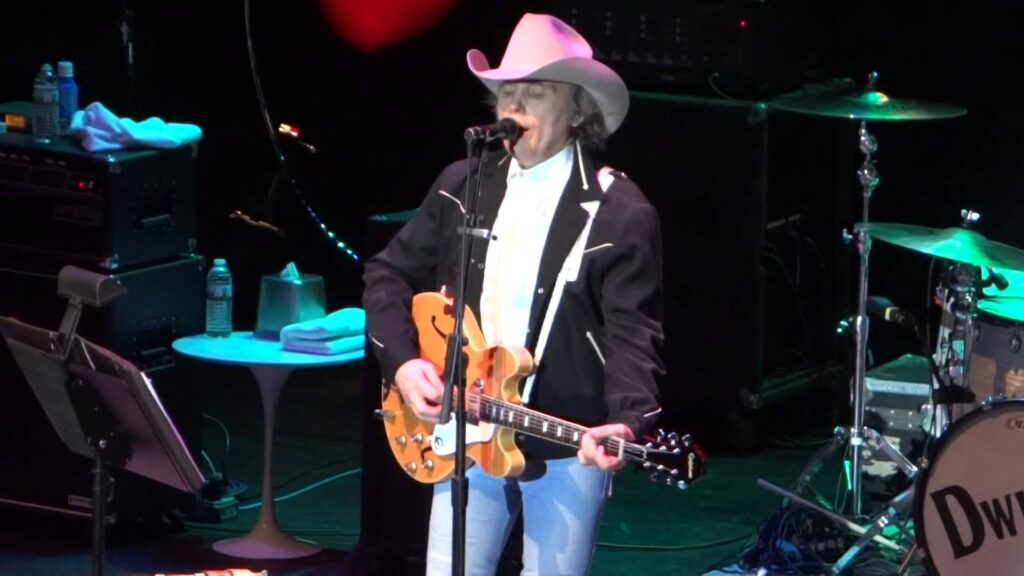

When Dwight Yoakam released A Long Way Home in 1998, both the song and its parent album of the same name marked a reflective turn in the Kentucky-born artist’s career. Though it didn’t climb high on the mainstream country charts—by that time Yoakam’s brand of Bakersfield-inspired honky-tonk had become an outlier amid Nashville’s pop-leaning direction—the record stood as a quietly defiant statement. It reaffirmed his devotion to the unvarnished emotional honesty that had always set him apart. After a decade defined by critical acclaim and restless experimentation, Yoakam was circling back to the roots of his sound: twang-laden guitars, lonesome harmonies, and that unmistakable tremor in his voice that made every word feel carved from heartbreak itself.

A Long Way Home, both as a song and an album, exists in that bittersweet space where nostalgia wrestles with self-knowledge. The track unfolds like a confession delivered on a late-night drive—one eye on the rearview mirror, another on the uncertain horizon. Yoakam’s songwriting here is steeped in classic country motifs—distance, regret, endurance—but it avoids sentimentality through sheer authenticity. His narrator isn’t wallowing; he’s reckoning. The title phrase becomes more than a geographical observation—it’s an emotional condition, describing the long journey toward forgiveness, toward reconciliation with one’s past mistakes, and toward the fragile hope of return.

The arrangement mirrors this inward journey. Guitars shimmer with a dusty melancholy reminiscent of the California desert landscapes Yoakam so often invokes. There’s a deliberate pacing to the rhythm section, evoking the slow passage of miles on an endless highway. Beneath it all runs an undercurrent of resilience—a recognition that even when love has faltered and distance has widened, something essential remains unbroken. It’s this tension between loss and persistence that gives the song its enduring weight.

By 1998, Yoakam was no longer simply a revivalist of West Coast country traditions; he had become their modern custodian. A Long Way Home captures him synthesizing decades of influence—from Buck Owens’ sharp-edged honky-tonk to the introspective melancholy of Roy Orbison—into something unmistakably personal. The song feels timeless because it’s rooted not just in genre but in human truth: every listener has their own “long way home,” a journey defined by mistakes survived and lessons earned.

In that sense, Dwight Yoakam’s “home” is not merely a place but a spiritual destination—a return to authenticity in an era chasing polish and perfection. The road may be long, but in his music, every mile carries meaning.