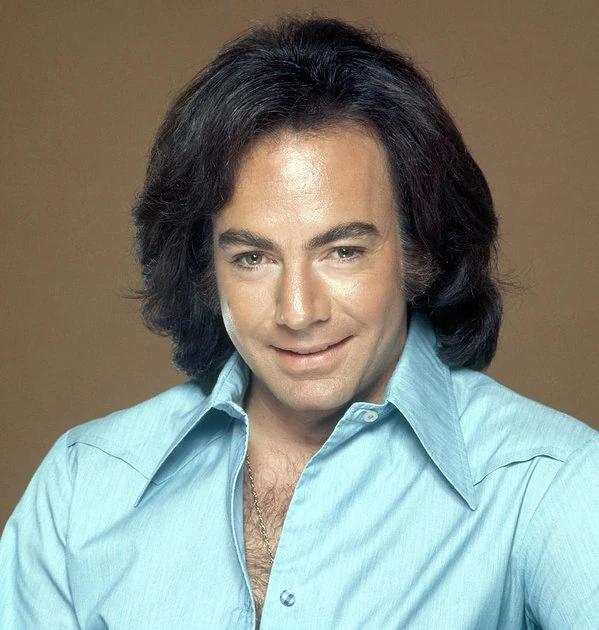

In Neil Diamond’s hands, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” becomes a soft-spoken act of mercy—holiday light offered to anyone whose December carries shadows, too.

There’s a reason “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” has never felt like mere tinsel. Even in its title, you can hear the restraint: have yourself—not “we will,” not “everything is wonderful,” but a gentle permission, almost a blessing spoken carefully so it won’t break. When Neil Diamond sings this classic, he leans into that tenderness rather than polishing it into easy cheer. He treats the song like a letter written at the edge of a quiet evening—warm, steady, and deeply aware that comfort is sometimes the only kind of celebration a person can manage.

To understand why the song hits so quietly hard, it helps to remember where it began. “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” was written by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane for the 1944 MGM film Meet Me in St. Louis, introduced by Judy Garland in a scene that is famously more tearful than festive. The song’s earliest lyric drafts were even darker than what audiences ultimately heard—so stark that Garland reportedly pushed back, wanting something less crushing to sing in that moment. Over time, the lyric continued to evolve: Frank Sinatra later requested changes that made the message more outwardly hopeful, swapping in phrases like “Hang a shining star upon the highest bough,” which is why different versions of the song carry slightly different emotional temperatures. The DNA, though, remains unmistakable: this is a Christmas song that admits the world can be difficult, and still dares to offer a small candle of hope.

That’s exactly the emotional door Neil Diamond walks through.

His recording of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” is tied not to a one-off single moment, but to his holiday catalog—specifically his album The Christmas Album, Vol. II (released in the mid-1990s). Later, this performance found a second life on compilations such as The Classic Christmas Album and A Cherry Cherry Christmas, which helped new listeners discover it long after its original release. In other words, Diamond’s version didn’t need to “arrive” with fireworks on the charts to become meaningful. It traveled the way many holiday recordings travel: quietly returning each year until it feels like it has always belonged on the soundtrack of December.

What makes Diamond’s interpretation “expensive”—the kind of detail you feel rather than merely hear—is his maturity of tone. By the time he recorded it, he had already lived inside enough songs to understand what this one truly is: not a party number, but a gentle act of reassurance. He doesn’t oversing. He doesn’t rush for climaxes. He allows the lyric’s bittersweet spine to remain intact, which is crucial. This song isn’t trying to hypnotize you into happiness; it’s trying to accompany you there, slowly, if you’re willing.

And that is where Diamond excels—companionship.

His voice carries a grain of lived experience, the sound of someone who knows that “merry” can be complicated. When he reaches the lines about troubles being “out of sight,” he doesn’t sell it like a guarantee. He offers it like a wish. The phrase that has always defined the song—“Until then, we’ll have to muddle through somehow”—is where the heart of it lives, and Diamond tends to sing that emotional truth without flinching. He doesn’t try to rescue the listener from sadness with glitter. He sits beside the sadness, which—strangely and beautifully—often makes it feel lighter.

Musically, his version is shaped to cradle the vocal rather than compete with it: a patient tempo, a classic holiday warmth, and an arrangement that feels designed for reflection, not spectacle. The result is the kind of track you put on when the house has gone quiet—when the lights on the tree are doing most of the talking, and memory is unusually close.

If you want the real meaning of “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas”—especially through Neil Diamond—it’s this: joy doesn’t have to be loud to be real. Sometimes it’s a small decision to keep your heart open one more day. Sometimes it’s allowing yourself to feel the ache and still hang the star. Diamond’s recording honors that adult truth with a steady hand.

So his “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” doesn’t feel like a command to be happy. It feels like permission to be human—tired, hopeful, nostalgic, grateful, uncertain—all at once. And that, perhaps, is why the song keeps coming back each year, and why Neil Diamond’s voice fits it so naturally: because the most enduring holiday comfort isn’t the kind that denies pain, but the kind that knows how to stand gently beside it and say, without drama, I’m here.