“Mr. Greed” is Fogerty’s hard stare at appetite without conscience—an old-rocker’s warning that when possession becomes a religion, it starts eating the people who kneel to it.

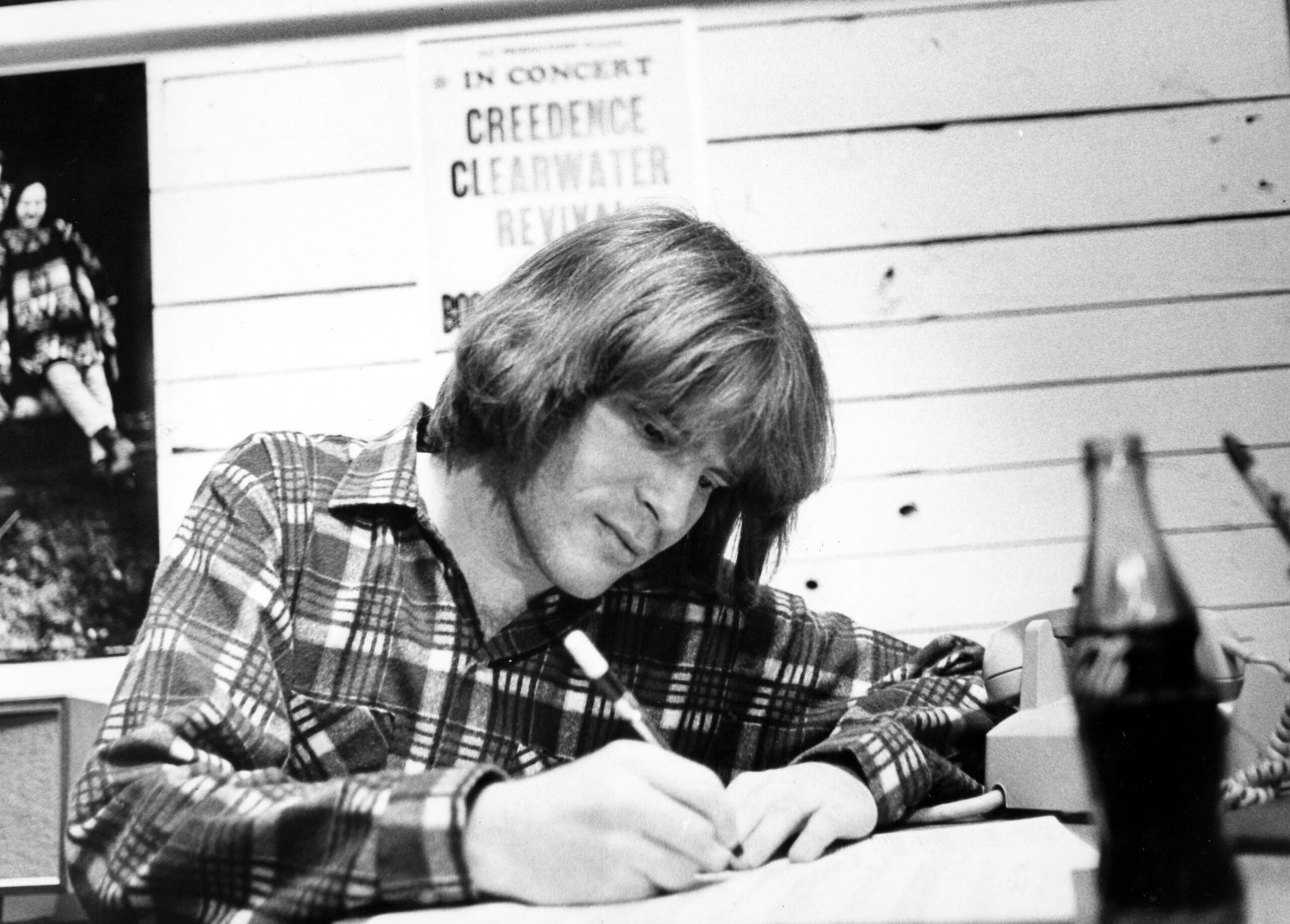

“Mr. Greed” arrived as the fifth track on John Fogerty’s comeback album Centerfield, released January 14, 1985. The album mattered immediately: it peaked at No. 1 on the US Billboard 200 and was later certified double-platinum (2× Platinum) by the RIAA—a rare solo triumph for an artist returning after years of silence. And that silence was real: Centerfield was Fogerty’s first new studio album in nine years, following the shelved Hoodoo project and a long retreat shaped by legal conflict with his former label.

Placed right in the middle of that triumphant return—after the radio muscle of “The Old Man Down the Road” and the easy motion of “I Saw It on T.V.”—“Mr. Greed” feels like the moment Fogerty stops smiling for the photograph. It closes Side One on the original LP sequence, like a door being shut with intention.

The song’s meaning is written in its address. Fogerty doesn’t sing about greed; he sings to it, personifying it as a living figure—an entity that buys, chains, consumes. That choice matters, because it turns an abstract vice into a character you can picture standing in the doorway: polished shoes, empty eyes, pockets full of other people’s time. In the 1980s, when the language of “more” was everywhere—more profit, more leverage, more acquisition—Fogerty answers with a blunt, almost old-fashioned moral clarity: this hunger is not progress; it is rot.

And there’s a sharper edge beneath the general message. Contemporary commentary and later retrospectives have noted that “Mr. Greed”—alongside “Vanz Kant Danz”—was widely interpreted as reflecting Fogerty’s bitter financial dispute with Fantasy Records and its head, Saul Zaentz. Fogerty had lived the most personal version of the song’s accusation: the feeling of watching someone else hold the keys to what you created, to your own name in the world, while you stand outside the building listening to the party you paid for. Even if the lyric never signs a legal document in ink, the emotional ink is unmistakable.

What makes “Mr. Greed” especially poignant on Centerfield is how it contrasts with the album’s brighter mythology. “Centerfield” (the song) is all Americana joy—baseball, hope, the faith that you can still be “put in, coach.” But “Mr. Greed” is the shadow that belongs to any honest comeback: the part where you admit why you left, what it cost, and what you refuse to swallow anymore. It reminds you that nostalgia isn’t always a warm blanket; sometimes it’s a ledger.

Musically, it’s built like a warning siren—tight, riff-driven, impatient with ornament. It doesn’t wander; it marches. Fogerty recorded Centerfield largely by himself through overdubbing, and that self-contained method adds a subtle psychological weight here: one man, alone with his instruments, carving the sound of his grievance into tape. The performance feels less like a band debate and more like a personal verdict.

And yet, for all its bite, “Mr. Greed” isn’t just anger. It’s grief, too—grief that people can be bought, that freedom can be chained, that art can be turned into paperwork. That’s why the song still lands decades later: it’s not tied to one headline. It’s tied to a pattern of human behavior that keeps repeating, wearing new suits in each era.

So when you play “Mr. Greed” now, try hearing it as a companion piece to the album’s victory. Centerfield went to the top, yes. But Fogerty didn’t return just to celebrate. He returned to testify—about ownership, about dignity, about the moment a man decides he’d rather be broke than be owned. And in that testimony, “Mr. Greed” becomes more than a track on Side One: it becomes the price tag Fogerty tore off and tossed onto the floor.