“Cruise to Harlem” is David Cassidy dreaming past the headlights—a midnight ride toward warmth, history, and a kind of soul-music refuge he couldn’t quite find in the charts, but could find in the song.

“Cruise to Harlem” sits in one of the most bittersweet corners of David Cassidy’s discography: it’s a deep cut with famous fingerprints. The song was co-written by David Cassidy, Gerry Beckley (of America), and—most surprisingly—Brian Wilson (founding member of The Beach Boys). That alone makes it feel like a secret meeting at the crossroads of 1970s West Coast pop craft: three writers who understood harmony, longing, and the way a melody can sound like a place you’ve never been but somehow miss.

The recording belongs to Cassidy’s elusive RCA-era finale, the album Gettin’ It in the Street. In the simplest terms, it was released in Germany and Japan in November 1976, but in the United States it became almost a phantom: copies were pressed, yet the album was not officially released, later turning up in 1979 in remainder “cut-out” bins—part of why it’s still spoken of with collector’s reverence. The record didn’t reach the album charts, and “Cruise to Harlem” itself was not a charting single—its life has always been more intimate than statistical.

Depending on which pressing or track listing you consult, you’ll see the song placed slightly differently: some list it as track 6 in the album sequence, while fan documentation for the original side breaks shows it on Side One as track 2 (with a listed duration around 3:08). Either way, it functions like the album’s soft center—where the pace eases, the night air cools, and the lyric stops trying to impress anyone.

And what a title it is: “Cruise to Harlem.” Harlem is not just a neighborhood name—it’s a symbol. It carries the echo of the Harlem Renaissance, the long lineage of jazz, soul, gospel, and the city-night romance of American music itself. Cassidy doesn’t approach Harlem like a tourist postcard. In the song’s best moments, Harlem feels like an idea: a place where feeling is allowed to be loud, where heartbreak can wear a sharp suit, where the streetlights understand your secrets. You can hear the wish behind the words: take me somewhere real—somewhere that knows how to hold a song.

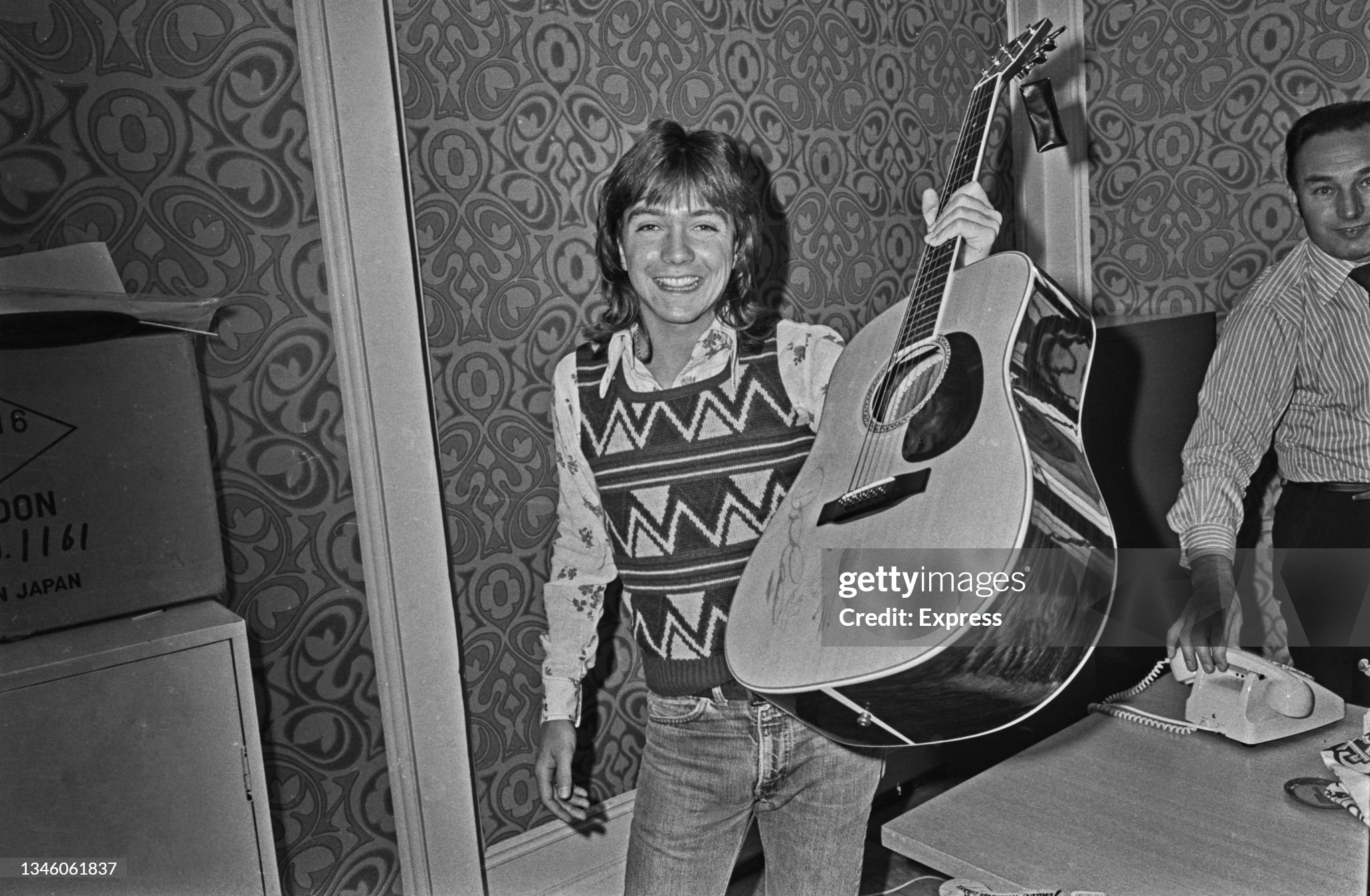

That wish fits the era Cassidy was in. Gettin’ It in the Street was his third and final RCA album, and (as widely noted) it would become his last U.S. album release for years. By 1976, he was no longer the carefully framed teen idol; he was trying—sometimes awkwardly, sometimes beautifully—to be judged on adult terms: songwriting, collaborators, atmosphere, and emotional grain. The album itself was co-produced by Cassidy and Gerry Beckley, which makes “Cruise to Harlem” feel even more personal: not just performed, but steered.

There’s also something quietly poignant about Brian Wilson being in the writing credits. Wilson’s own story is one of genius, fragility, and longing for a kind of musical sanctuary. Beckley’s gift has always been melodic clarity—sunlight with a shadow. Cassidy, meanwhile, was trying to outrun an image while still honoring the voice people loved. Put those three sensibilities together and you get a song that feels like motion without escape: the car moves, the night opens up… yet the heart is still carrying what it carried at the start.

That is the deeper meaning of “Cruise to Harlem.” It isn’t really about geography. It’s about the human impulse to believe that one more turn of the road—one more song, one more street, one more glowing window—might rearrange the way you feel inside. It’s about choosing romance not as fantasy, but as medicine: music as a destination, not just something playing in the background.

Maybe that’s why the track has aged so gracefully. Because it was never overplayed, never worn thin by radio repetition. It remained—like a favorite late-night route you only take when you need it. And when you hear David Cassidy sing it now, you don’t just hear a man chasing a sound. You hear an artist trying to find a place where the past stops shouting, the future stops demanding, and the present—just for three minutes—feels like a ride you can finally settle into.