“Fallen Angel” is the Bee Gees’ late-career ache in miniature—an elegy for innocence, sung with the calm of men who’ve learned that some losses don’t shout, they linger.

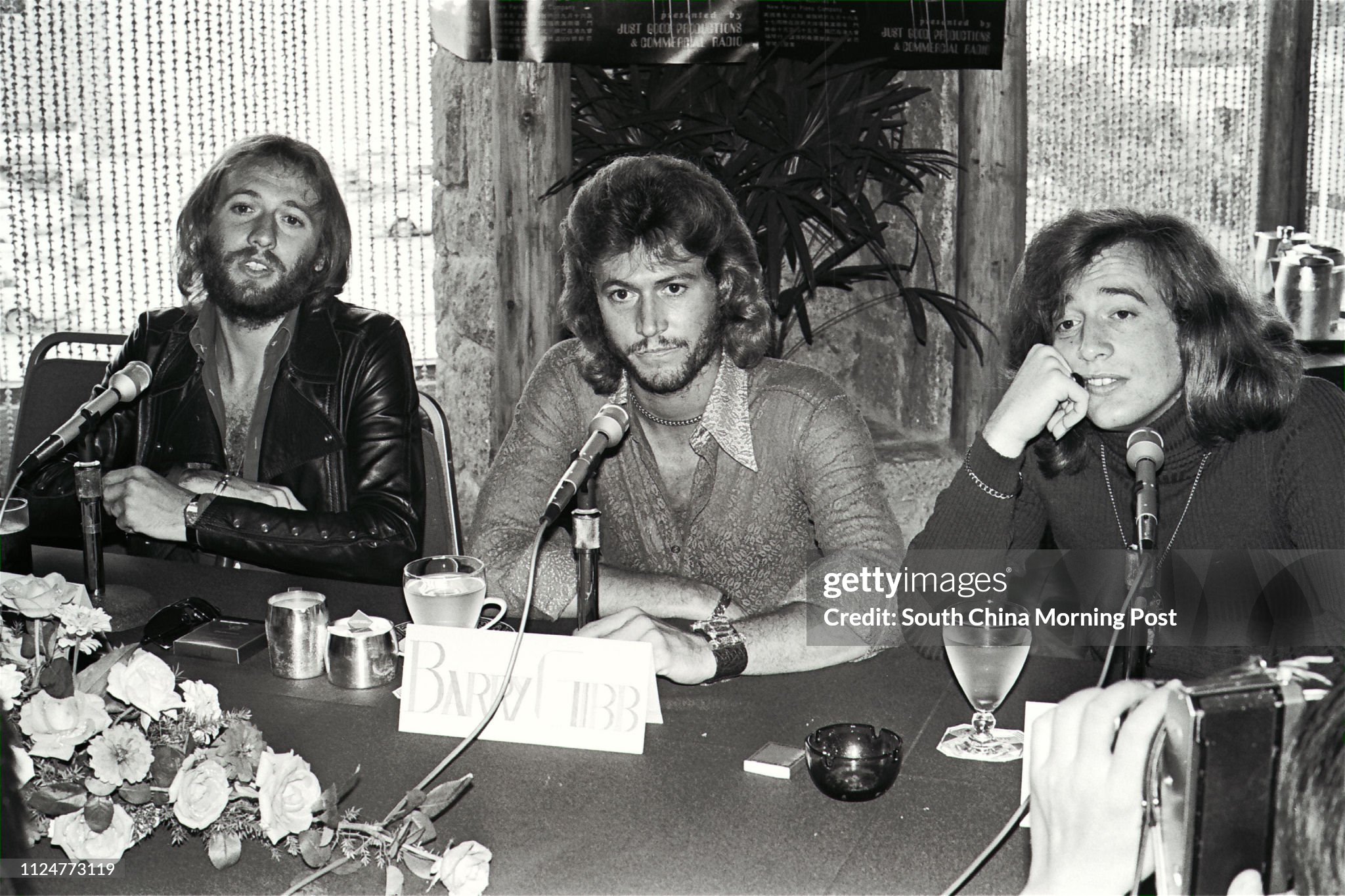

The essential facts belong right at the top, because they explain why this song feels like a secret kept in plain sight. “Fallen Angel” is an album track on the Bee Gees’ 20th studio album Size Isn’t Everything, released 13 September 1993 in the UK (and 2 November 1993 in the U.S.). It was written by the three Gibb brothers, and the lead vocal is by Robin Gibb. Importantly, “Fallen Angel” did not have a conventional “debut and peak” story on the big singles charts, because it wasn’t pushed as a primary A-side. Its most visible commercial appearance came later, as an extended remix used as the B-side on the UK single How to Fall in Love, Part 1 (released April 4, 1994), which peaked at No. 30 on the UK Singles Chart.

That “sideways” chart story suits the song’s personality. Fallen Angel isn’t built like a bid for mass approval; it’s built like a late-night thought you don’t say out loud in daylight. And it lives on an album that was, itself, a kind of statement. After the more contemporary dance sheen of High Civilization, the group described Size Isn’t Everything as a return toward their pre-Saturday Night Fever sound—a subtle but meaningful act of self-reclamation. The album performed solidly in the UK, peaking at No. 23, though it was much less successful in the U.S. (peaking at No. 153 on the Billboard 200). In other words: in the early ’90s, the Bee Gees were no longer the unavoidable center of the pop universe—yet they were still capable of making records with real emotional gravity, records that found their listeners the way certain voices always do: steadily, loyally, almost privately.

So what is “Fallen Angel” actually doing?

It’s singing to the part of us that suspects a fall isn’t always a scandal—sometimes it’s simply life taking its due. The phrase “fallen angel” carries a double ache: it suggests beauty that has been damaged, purity that has learned too much, a once-bright spirit now walking the earth with dust on its shoes. In Robin Gibb’s hands, that idea becomes less gothic imagery and more human biography. His voice—always quivering with a kind of noble sorrow—makes the title feel like a name you whisper with tenderness rather than judgment.

The early ’90s were a complicated season for legacy artists: radio tastes had shifted, critics could be fickle, and nostalgia could feel like a cage if you let it. That’s why Size Isn’t Everything matters as a backdrop: it’s an album made by men who’d already been adored, dismissed, rediscovered, and adored again. When they sing about a “fallen” figure here, you can hear the wisdom of experience behind the melodrama—an understanding that survival itself leaves marks.

There’s also a quiet poignancy in what happened around this era: according to the long-running session chronicle by Joseph Brennan, a major 1994 tour was planned to promote the album but was called off due to health issues Barry Gibb was dealing with, including arthritis-related problems. That doesn’t “explain” the song, but it colors the atmosphere around it—because when movement is limited, memory gets louder, and the inner life becomes the stage.

And perhaps that’s the lasting meaning of Fallen Angel: it’s not merely about a person who fell. It’s about the way we keep loving what’s bruised—within ourselves, within others, within the past. The Bee Gees had always been masters of harmony, but here the harmony feels like something else too: three brothers—Robin, Barry, and Maurice Gibb—holding a small flame steady against the draft of time.

Some songs win their place through chart peaks. “Fallen Angel” wins its place the quieter way: by sounding, year after year, like the truth you only admit when the house is finally still.