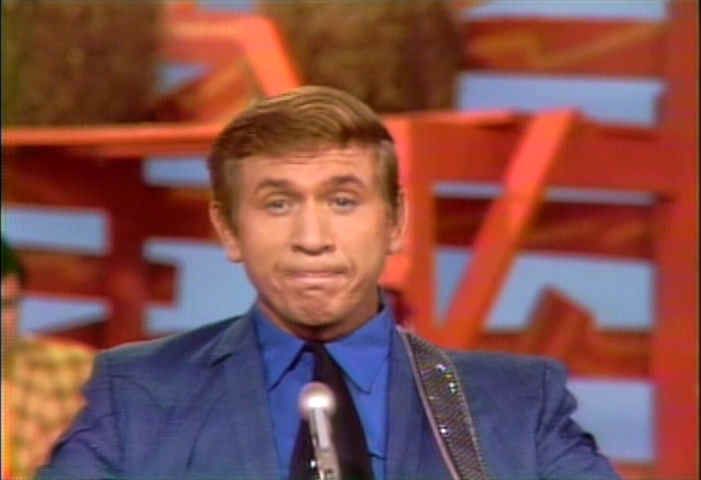

A stoic early-Bakersfield heartache—pain carried with a straight back and a steady stare

“It Don’t Show on Me” is one of those early Buck Owens songs where the mask does the talking. Written and recorded by Owens, it first appeared as a Pep Records 45 in 1956—catalog Pep 105—backed with “Down on the Corner of Love.” The single did not chart nationally; Owens wouldn’t dent the country lists until “Second Fiddle” in 1959, followed by the Top 5 “Under Your Spell Again.” In time, the track was gathered onto his first long-player, Buck Owens (La Brea L-8017), a pre-Capitol LP issued around 1960–61 whose track list plainly includes “It Don’t Show on Me.” In short: an unheralded A-side that introduced a voice the world was just beginning to hear.

The story behind it is pure Bakersfield. In 1956, Owens was cutting his first solo sides at Lewis Talley’s studio for the tiny Pep label—tough, twangy, independent of Nashville’s velvet sheen. Those singles went largely unnoticed at the time, but they turned heads among insiders and planted the seeds of what would be called the Bakersfield Sound: sharp guitars, a back-porch rhythm feel, and an emotional plain-spokenness that felt closer to a dancehall than a drawing room. “It Don’t Show on Me” belongs to that first handful—raw, spare, sung like a man telling you the truth over the bar rail.

Chart context at release. There isn’t one for the song itself—that’s part of its quiet dignity. Owens’ earliest Pep and La Brea sides didn’t register on Billboard; as several histories note, his first nine singles failed to chart before 1959’s “Second Fiddle” opened the door and “Under Your Spell Again” climbed to No. 4. So while “It Don’t Show on Me” never carried a number beside its name, it stood at the starting line of a career that would deliver 21 country No. 1s in the decade to come.

Listen closely and the meaning is in the title. The lyric keeps repeating an insistence that sorrow is invisible—“You can’t know the feeling inside me… you can’t know ’cause it don’t show on me”—and each return to that phrase makes the façade tremble just a little more. Owens’ writing is the essence of country stoicism: the pain is acknowledged, but never paraded. If you grew up with transistor radios and two-steps on a Saturday night, you’ll recognize that posture—the old resolve to carry heartbreak without spectacle.

Musically, you hear the pre-Capitol contours: a brisk two minutes (just about 1:58 on later transfers), unfussy band, electric guitars bright but not flashy, and a vocal that rides the beat instead of decorating it. Owens doesn’t over-emote; he leans into his slightly nasal timbre and lets the consonants do the cutting. That restraint is precisely what makes the feeling land—the song is a portrait of composure as self-defense.

The track’s afterlife tells its own tale. Though born on a tiny label, “It Don’t Show on Me” kept resurfacing—folded into the La Brea LP Buck Owens and later anthologized on collections like His Earliest Recordings and Early Recordings 1956–1961. For longtime fans, those reissues felt like finding an old photograph: the face is younger, the lines softer, but the look in the eyes is the same. You can already hear the instincts that would define the Buckaroos era—economy, clarity, and that Bakersfield bite.

There’s also something quietly biographical embedded here. In ’56, Owens was still hustling—playing sessions, writing with friends, even moonlighting as rockabilly “Corky Jones.” He hadn’t yet built the Crystal Palace or conquered Hee Haw; he was a working musician with rent to pay and a point of view to defend. A song about keeping sorrow hidden fits that chapter: not self-pity, but self-control. It’s the emotional grammar of the Bakersfield working class—show up, sing true, and don’t let the world see you flinch.

What lingers after the needle lifts is the feeling of recognition. For older listeners, “It Don’t Show on Me” sounds like the code you grew up with—heartache acknowledged between friends, not broadcast for applause. For newer ears, it’s a master class in how little a great country song needs: a sturdy hook, a human voice, and a truth you can’t improve by saying louder. The charts may have ignored it in 1956, but the song quietly helped map the road to everything that followed—right up to the Capitol hits and the long run of number ones. Sometimes the foundation stones are the ones nobody notices at the time. This is one of them.