A Stoic Meditation on Loss Wrapped in the Easy Lilt of a Barroom Ballad

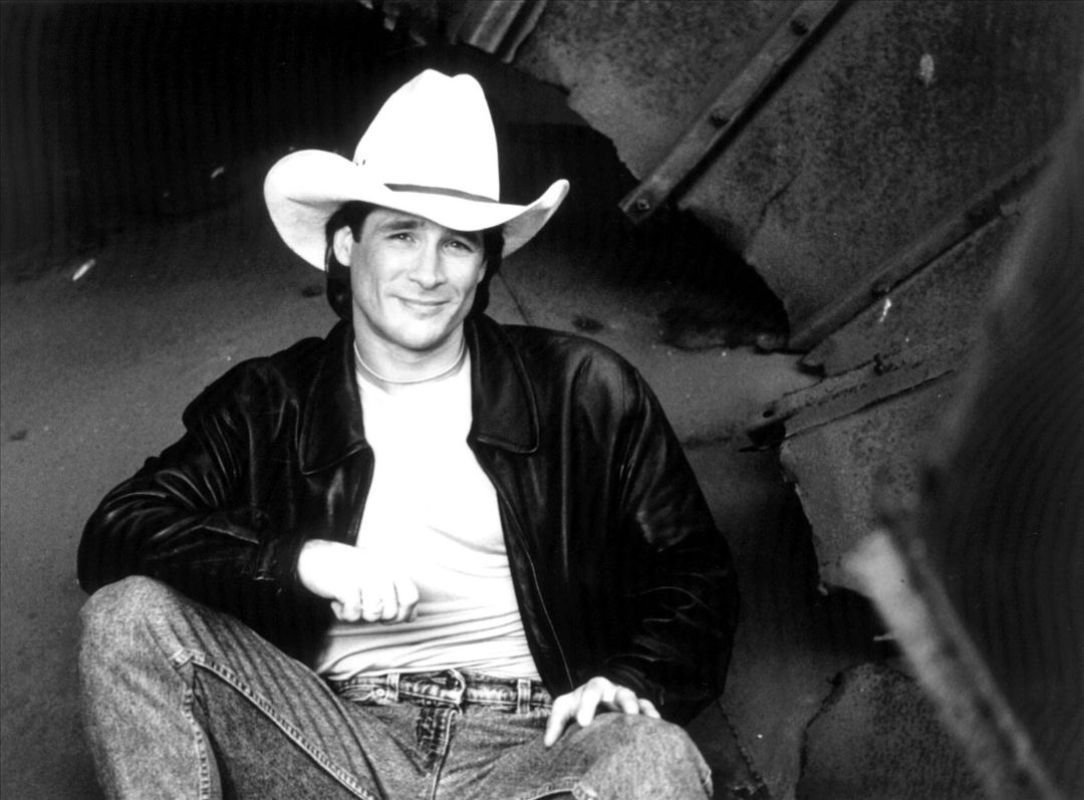

When Clint Black released “Killin’ Time” in 1989, he wasn’t just introducing a single—he was announcing the arrival of a distinct voice in country music, one that melded traditionalism with lyrical introspection. The song, released as the title track from his debut album Killin’ Time, swiftly climbed to the top of the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, where it held the number one position for three consecutive weeks. It followed his breakthrough hit “A Better Man,” and together, these songs heralded one of the most impressive debuts in country music history. As “Killin’ Time” took its place atop the charts, it became both an anthem and an elegy—capturing the kind of pain that comes not in stormy outbursts, but in quiet, drawn-out evenings with too much whiskey and too few tomorrows.

Beneath its mid-tempo sway and accessible twang lies a masterclass in lyrical economy. Co-written by Clint Black and Hayden Nicholas, “Killin’ Time” is ostensibly about a man trying to drink away heartbreak. But as is often the case with great country songwriting, the metaphor stretches deeper. The act of “killing time” becomes a fatalistic endeavor; each drink, each memory revisited, is both an escape and a slow surrender. The line “You were the one who taught me how to forget / And now you teach me how to live again” pivots with devastating irony—not toward hope, but toward resignation.

The genius of Black’s writing is in how it disguises existential despair beneath the comfort of familiar instrumentation. The song leans on warm acoustic guitars and pedal steel that echoes like a long sigh across an empty barroom floor. Its structure is simple—no frills, no theatrical modulation—just a steady shuffle that allows the lyrics to cut quietly deep. It evokes that peculiarly American melancholy: stoic, self-aware, always just on the edge of tears but too proud to show them.

“Killin’ Time” arrived at a pivotal moment in country music’s timeline—a period dominated by polished production and pop-leaning sensibilities. Yet Black stood at the vanguard of what would soon be known as the New Traditionalist movement. Alongside contemporaries like Alan Jackson and George Strait, he pulled Nashville back toward its roots, embracing storytelling with grit and poetic candor.

In hindsight, what makes “Killin’ Time” endure is not just its commercial success or its role in launching Black’s illustrious career. It’s the way it dares to stare down emotional ruin without flinching. The song doesn’t offer redemption or clarity—it offers companionship in sorrow. For anyone who has ever found themselves watching the hours dissolve into bourbon-colored blur, “Killin’ Time” isn’t just a song—it’s a mirror. And sometimes, all we want from our music is to know we’re not alone as we sit with our pain and wait for time to kill us back.