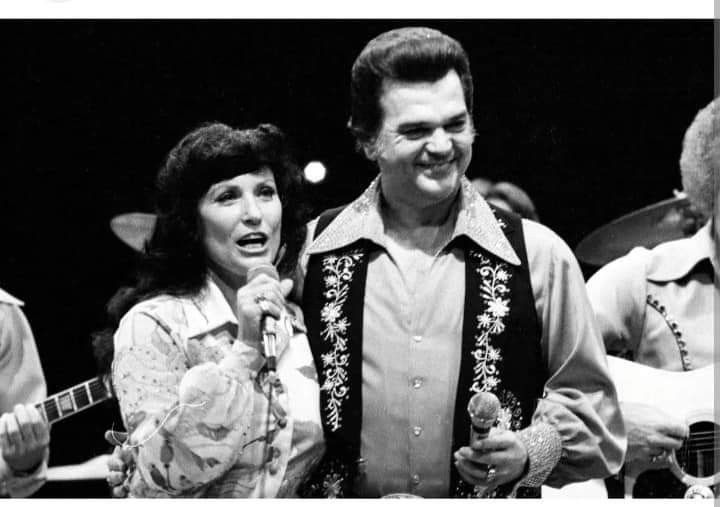

Two voices on opposite banks, daring the river to shrink—Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn’s “Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man” makes distance sound conquerable and love feel like muscle memory.

Let’s set the anchors before we drift down the current. “Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man” was written by Becki Bluefield and Jim Owen, produced by Owen Bradley, and cut at Bradley’s Barn in Mount Juliet, Tennessee. Issued by MCA on May 28, 1973, it was the first single and title song from the duo’s album Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man. The record did what their voices always threatened to do together: it went straight to the top—No. 1 on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles (one week at the summit; 13 weeks on the chart) and No. 1 in Canada on the RPM Country Singles list. On the album side, the LP followed in July 1973 and topped Billboard’s Hot Country LPs, proof that listeners wanted the whole story, not just the single.

If you like your memories with a date stamp, the song reached No. 1 on August 18, 1973—the kind of late-summer chart week that sticks in a fan’s scrapbook, because you can still feel the heat in the groove.

What you hear first isn’t just harmony; it’s dialogue. She’s on the Louisiana side, he’s over in Mississippi, and the Mississippi River is less geography than an obstacle to be out-sung. The lyric is simple on purpose—promises shouted across water—and the production gives those promises a body: up-tempo Cajun feel, fiddles and guitars nipping at the beat, the two leads trading lines like oars dipped in time. Even Billboard heard the regional spice when it was new, praising the track’s “up-tempo Cajun sound” and how beautifully the pair fit inside it.

Part of the song’s charge is context. By 1973, Twitty and Lynn were not a novelty—they were an institution—and this became their third country No. 1 as a duo, after “After the Fire Is Gone” and “Lead Me On.” They’d learned how to square their different strengths: his smooth, river-stone baritone; her quicksilver edge that could cut or console as needed. Put those colors on a tune about closing distance and you get a record that feels both playful and inevitable—a flirt that hardens into a vow by the final chorus.

The album Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man extends that mood. Tracked through March–April 1973 and released July 9, 1973, it wears Bradley’s touch—clean, warm, built to last—and it climbed to No. 1 on the country LP chart while crossing to No. 153 on the main Billboard list. Title cuts don’t always define their albums; this one does, setting a bright, winking temperature the sequenced songs keep returning to.

For older ears, the song’s usefulness is what endures. It isn’t a lecture about devotion; it’s a procedure: name the distance, declare your intent, and move. Twitty leans into the groove with a steady grin; Lynn answers like someone who’s done harder work than swimming a mile. Between them, they make confidence sound hospitable. It’s dance-floor music, yes, but it’s also kitchen music—the kind you hum while you fold laundry or finish a long day, reminder that love often wins by showing up more than showing off.

There’s a little epilogue worth pinning. Decades after that summer, the single earned a Gold certification from the RIAA—half a million sales’ worth of proof that the record kept walking into new rooms, new stereos, new lives. Songs about distance don’t go out of date; rivers keep running.

Scrapbook pins, neat and true

- Song/Artists: “Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man” — Conway Twitty & Loretta Lynn; writers: Becki Bluefield / Jim Owen; producer: Owen Bradley; studio: Bradley’s Barn (Mt. Juliet, TN).

- Release: May 28, 1973 (MCA); B-side: “Living Together Alone.”

- Charts: Billboard Hot Country Singles #1 on Aug 18, 1973 (1 week at #1; 13 weeks on chart); RPM Canada Country #1.

- Album: Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man (released July 9, 1973); Hot Country LPs #1; Billboard Top LPs & Tape #153.

- Note: Duo’s third U.S. country No. 1 as a pair; single later RIAA Gold.

Play it again and notice what happens to the room. Your shoulders drop; your feet start to mark time. Two singers call across a river and, for three easy minutes, the river seems smaller. That’s not just a hook—it’s a habit of hope—and it’s why this one still feels like summer on the tongue, all these years later.