A pop prayer about where songs come from—“I Write the Songs” lets David Cassidy turn doubt into devotion, singing not of ego but of the larger spirit that moves through music and through us.

Key facts first. Before Barry Manilow took Bruce Johnston’s tune to No. 1 in America, David Cassidy got there first in the U.K. Issued in May 1975 as a double-A side with “Get It Up for Love,” Cassidy’s “I Write the Songs” climbed to No. 11 on the Official Singles Chart that August. He cut it for his RCA comeback album The Higher They Climb, The Harder They Fall—a set co-produced with Johnston—which itself reached No. 22 on the U.K. albums list. Only months later would Manilow’s reading top the Billboard Hot 100 in January 1976; Johnston had first placed the song earlier still, on Captain & Tennille’s Love Will Keep Us Together (May 1975). Those timelines matter, because they put Cassidy in the song’s first wave, shaping how many listeners outside the U.S. heard it.

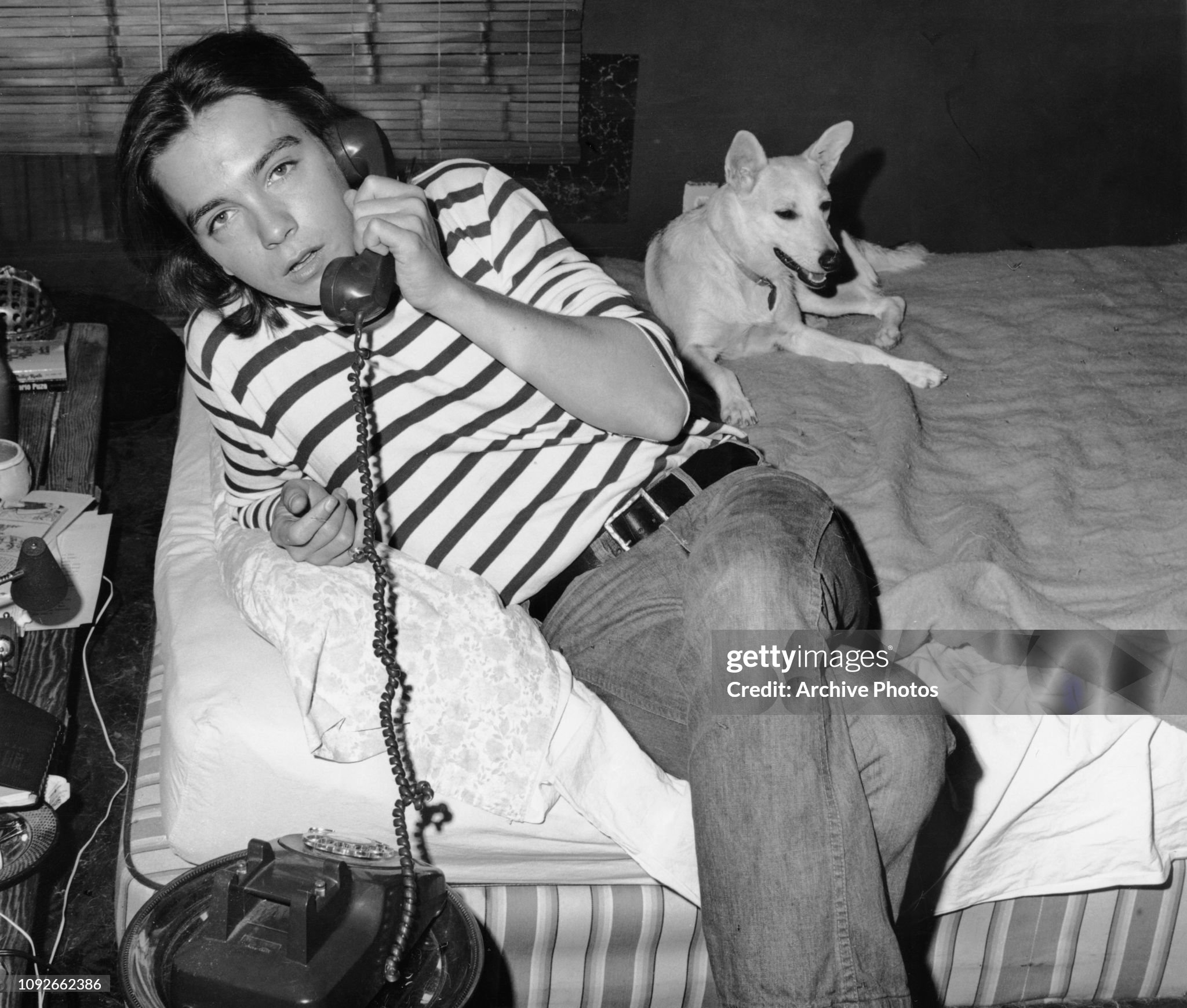

What Cassidy brings is tone—gentle, grateful, a little weathered for a 25-year-old. Johnston (of the Beach Boys) didn’t write a brag; he’s said the song’s “I” is not a pop star at all, but the creative spirit itself. Cassidy leans hard into that reading. He sings like a man who has felt the machine’s grind and wants to remember why you sing in the first place. That’s why the record felt like a hinge in 1975: no longer the boy from the posters, he stands still and lets a big idea wear a small smile.

The sound frame is West Coast elegant. On the album cut, Johnston surrounds Cassidy with Los Angeles aces in quiet, tasteful colors—electric piano and piano in soft conversation (Bruce Johnston and John Hobbs), clean guitar figures (Bill House), a rhythm section that moves without show (Jim Gordon, Emory Gordy Jr.), and a discreet shimmer of harmony that includes Carl Wilson—a subtle blessing from the Beach Boys’ choir. It’s all arranged to make Cassidy’s tenor feel unforced: the verse confides, the chorus opens, and nothing crowds the lyric’s humility.

If you lived with this single when it was new, you may remember the double-A pacing: flip from the sly Ned Doheny groove of “Get It Up for Love” to this measured, almost prayerful statement and you hear a singer repositioning himself in real time. The public heard it too; that No. 11 peak marked a sturdy U.K. return after the early-’70s shriek of Partridge-era fame had faded. And when Manilow’s U.S. smash arrived months later, it confirmed the song’s reach across styles: a durable melody carrying an idea bigger than one voice.

What does the song mean, sung by David Cassidy in that moment of his life? It isn’t a claim of authorship so much as a confession of stewardship. “I write the songs” here sounds like a craftsman saying, I serve the thing that moves through me. Older listeners hear the wisdom in that. After a certain age you know the difference between applause and purpose; you know that any real gift—parenting, teaching, loving, making—asks for tending more than triumph. Cassidy—fresh to a new label, freshly serious—lets the lyric become an ethic: be faithful, be useful, be kind to the music that chose you.

There’s also the texture of time in his voice. He sings without the starched diction of a formal balladeer; there’s a human grain that suits lines about songs “that make the whole world sing.” Where later versions soar, Cassidy’s sits with you. The chorus lifts, yes, but the lift is domestic—kitchen-radio, soft-evening light—more gratitude than grandstanding. It’s the sound of a man thanking the thing that kept him company when the fever broke.

Placed inside The Higher They Climb, the track is a kind of thesis. The album’s repertoire—Spector and Wilson touchstones, Doheny’s slick California soul, Cassidy’s own writes—spells out a path away from bubblegum and toward adult pop craft. That the LP reached No. 22 in Britain says the audience recognized the attempt; that Cassidy’s single arrived before Manilow’s American triumph says he helped introduce the song’s spirit to pop radio rather than merely surfing its wave.

Listen now and the song’s kindness feels like the whole point. It doesn’t argue about authorship; it simply affirms that music arrives, and we do our best by it. Drop the needle and you may find yourself in rooms you haven’t visited in years: a living room with wood-grain speakers, a stack of RCA sleeves on the coffee table, someone you loved humming along because the words made sense even when life did not. Cassidy knew how to sing to those rooms. He still does.

And the facts that anchor the memory remain clear: first-wave 1975 recording under Bruce Johnston’s wing; double-A U.K. single with “Get It Up for Love,” peaking at No. 11; album The Higher They Climb, The Harder They Fall reaching No. 22; the song’s U.S. coronation later via Barry Manilow; and its original appearance that spring on Captain & Tennille’s LP. The charts tell you where it traveled. Cassidy’s reading tells you why it’s worth the trip: because sometimes the bravest thing a singer can do is admit the song does not belong to him—it belongs to the music.