A prairie hush at sunrise—Dwight Yoakam’s “Cattle Call” brings the old cowboy yodel into the late-century light, turning heritage into something tender, present, and steady.

Let’s set the anchors right up front. “Cattle Call” in Yoakam’s hands is best known as the opening track on the film album The Horse Whisperer: Songs From and Inspired by the Motion Picture (released April 7, 1998). On that soundtrack it runs a compact ~3:23–3:24 and appears track 1, before Allison Moorer, Lucinda Williams, Emmylou Harris and others carry the prairie mood forward. Yoakam’s version was not worked to radio as a single, but the placement—first song, first scene-setter—speaks volumes about its role in the album’s atmosphere.

There’s a clean lineage behind the title. “The Cattle Call” was written by Tex Owens in 1934, a cowboy hymn that Owens said came to him watching snowfall on livestock in Kansas City. It later became a career signature for Eddy Arnold, whose 1955 remake with Hugo Winterhalter’s orchestra sat on the Billboard country chart for 26 weeks and hit #1 for two weeks—the moment the tune truly entered the American bloodstream.

Yoakam’s relationship to the piece extends beyond the film: he later gathered this 1998 cut for his covers compilation In Others’ Words (2003), where it sits among tributes to Jimmie Rodgers, Bill Monroe, the Grateful Dead and more—a tidy reminder that Dwight has always treated other people’s songs like living rooms to inhabit, not museums to tiptoe through.

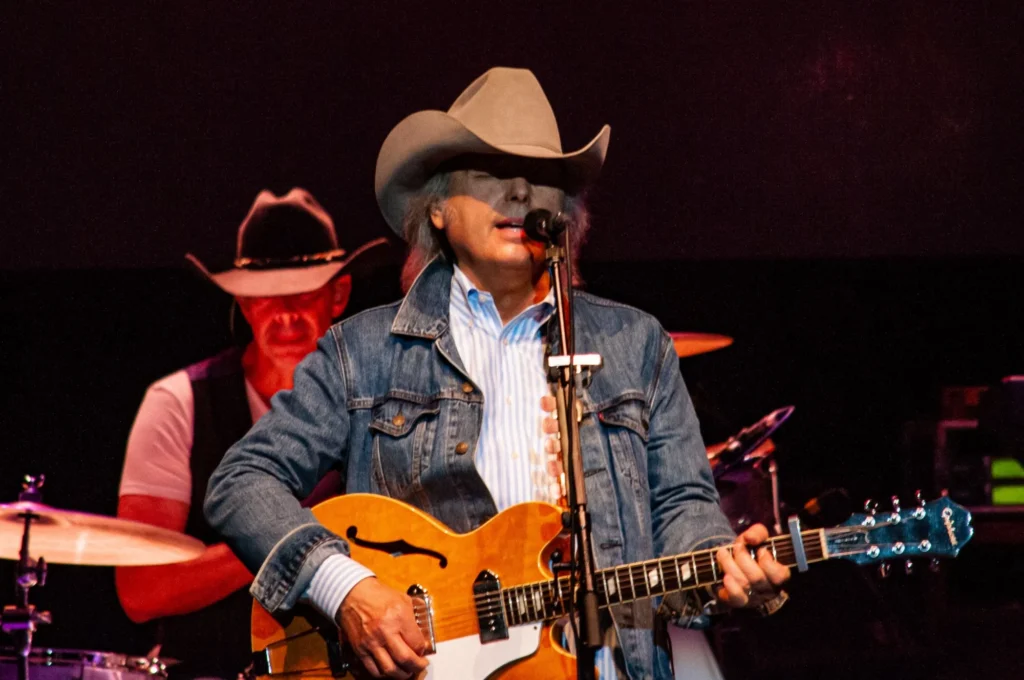

What does his version sound like? Contemporary reviews nailed the feel in a line: the soundtrack “begins with the ethereal yodel” of Yoakam’s “Cattle Call,” and from those first honest, unsentimental notes you’re out under big sky. He doesn’t over-dress the melody; he lets air in. The band moves at a walking pace, the vocal arcs are clean and unhurried, and the yodel—never a stunt—arrives like sunlight on fence wire. It’s Bakersfield bones with a frontier hush: a pocket that reassures rather than insists.

For older ears, that restraint is the point. Where Arnold’s blockbuster 1955 version gleamed with strings and chart-era sheen, Yoakam brings the song back to weather and work—the ritual sound a rider might make to gather scattered head in the cold of morning. You can hear why the film’s producers led with it: as soon as the yodel lifts, the record drops you into the West without postcards or bravado. The cut doesn’t perform cowboy myth; it keeps company with it. (Even the Christian Science Monitor’s capsule on the soundtrack called Yoakam’s take a “genteel introduction”—not a grandstand, a welcome.)

The story behind the song deepens the pleasure without weighing it down. Owens wrote it in the Depression years; Arnold recorded it multiple times (1944, 1949, 1955, 1963), and later dueted with LeAnn Rimes in the ’90s as new ears arrived at the music. Yoakam enters that timeline not to outsing anybody, but to tend the flame—to show that a cowboy call can feel modern if you treat it like a human voice in a big place. It’s a lesson he’s modeled across his career: carry the old forms forward with a player’s touch and a listener’s humility.

If you want the discography pins neat and true:

- Artist: Dwight Yoakam

- Song: “Cattle Call” — ~3:23–3:24; track 1 on The Horse Whisperer soundtrack (1998).

- Later appearance: In Others’ Words (2003) compilation, track 4.

- Origins: Written 1934 by Tex Owens; popularized by Eddy Arnold, whose 1955 version reached #1 country (two weeks) and spent 26 weeks on the chart.

But a song like this isn’t kept alive by ledgers; it’s kept alive by touch. Listen to how the beat sits a breath behind the bar—steady, unhurried. The guitar lines answer Yoakam’s phrases and then step back, the way conversation sounds when friends are watching the weather roll over a ridge. The yodel doesn’t flash; it locates you. If you ever grew up near stockyards or just drove past winter pasture with the heater on full, it will pull a memory forward you didn’t know you’d stored: the mix of loneliness and work, danger and daylight, and the odd comfort of hearing one voice carry across open air.

That’s the quiet wonder of Yoakam’s “Cattle Call.” He doesn’t try to improve a classic; he reinhabits it—brushing off the dust and letting the grain show. Played softly at night, it feels like a hand on a horse’s neck; played loud in the truck, it opens the road ahead a little wider. Either way, it proves what great country singers have always known: the past isn’t a museum—it’s a home range. And as long as someone can still stand in the morning chill and send a tune across it, the old places remain alive, and the heart remembers how to answer back.