A drifter’s prayer with a steady backbeat—“Lonesome Roads” finds Dwight Yoakam closing the door gently, owning the miles behind him and the ones he still has to walk.

Headlines first. “Lonesome Roads” is the final track on This Time, released March 23, 1993. While it wasn’t promoted as a stand-alone single, the cut did ride the flip of the album’s lead 45—“Ain’t That Lonely Yet”—on a U.S. Reprise 7-inch (7-18590) issued March 8, 1993. The parent album, recorded at Capitol Studios (Hollywood) and produced by Pete Anderson, became Yoakam’s biggest seller, peaking at No. 4 on Top Country Albums and going triple-platinum. Its A-side hits—“Ain’t That Lonely Yet,” “A Thousand Miles from Nowhere,” and “Fast as You”—all reached No. 2 on the country chart; “Try Not to Look So Pretty” and “Pocket of a Clown” followed into the Top 20. At just about three minutes (listed around 3:05–3:09 depending on edition), “Lonesome Roads” brings the album home with a plainspoken grace.

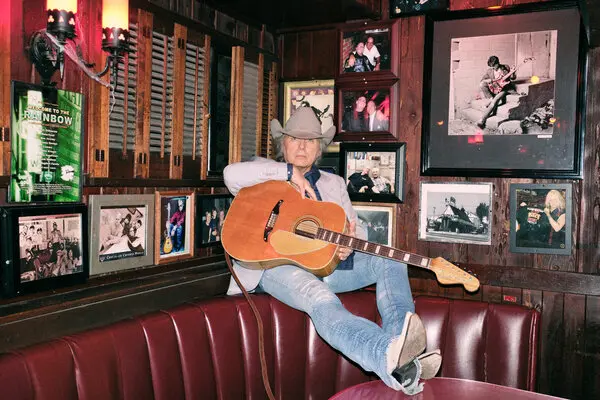

If you listen with the album’s story in your ears, this closer feels like a benediction. Across This Time, Yoakam and Anderson widen his Bakersfield grammar—clean Telecaster lines, pedal-steel ache—by letting little hints of early rock and soul flicker at the edges. You hear the same care in the finale’s frame: a warm, unfussy rhythm pocket; guitars that glint rather than glare; room for the vocal to carry the weight without theatrics. Yoakam’s narrator doesn’t rage; he owns who he is. Those “lonesome roads” aren’t a pose, they’re a habitat—a life learned on two-lanes and in empty rooms where pride and regret take turns at the window. (The album’s making was modern in its toolset, but stubbornly old-school in feel; the team finished it at Capitol, with Anderson steering the sound toward something recognizably Yoakam and nobody else.)

Part of the track’s authority comes from who’s in the room. The session credits around the album read like a West Coast all-star roll: Pete Anderson on electric guitar, Dean Parks on acoustic, Scott Joss and Don/“Dan” Reed on fiddles, Jeff Donavan on drums, Taras Prodaniuk on bass, and Al Perkins adding steel textures. Stacked harmonies fold in voices such as Jim Lauderdale, Beth Andersen, and Jim Haas—seasoned singers who know how to lift a line without crowding it. You can hear that practiced restraint in the way the chorus blooms and then settles back, like headlights cresting a hill and sliding into the next stretch of dark.

Lyrically, “Lonesome Roads” is a small masterclass in humility. Instead of dressing heartache up as destiny, the singer talks about habit: the kind of roads he always travels, the kind of places he ends up. There’s no self-mythology here—just the clean admission that solitude and motion have become second nature. For older listeners, that candor can land like a hand to the shoulder. After a certain age you recognize that the hardest truths are often the simplest ones, spoken without ornament: I’m built this way. I’m trying. I keep moving.

As a record, the cut also explains why This Time felt so large in 1993. The singles carried the headlines—strings and Roy Orbison shadows on “Ain’t That Lonely Yet,” the hypnotic sprawl of “A Thousand Miles from Nowhere,” the sly pop of “Fast as You”—but the closing track supplies the album’s conscience. It’s the late-night scene after the crowd has gone home, the part where bravado falls away and the work of being a person resumes. That balance—wide-open radio moments framed by songs that breathe—is why the LP still feels like a life, not just a run of hits.

The song’s afterlife confirms its quiet pull. Yoakam kept it in the set and captured a hardened-by-the-road version on Dwight Live (1995), where the tempo leans forward a hair and the band makes the refrain feel like a vow whispered on the bus at 2 a.m. He also stripped it to the studs on dwightyoakamacoustic.net (2000), a reminder that the melody and the bones hold without any studio polish at all. Those revisits tell you what the artist thought of it: this wasn’t a mere album track; it was a compass point.

What does “Lonesome Roads” mean now? For many of us, it’s a mirror we can stand in front of comfortably. The song doesn’t confuse movement with freedom; it recognizes that sometimes we keep moving because staying still would make us tell the truth faster. And yet there’s kindness in it—no sermon, no punishment, just a man measuring the cost of the life he’s chosen and finding a way to sing through it. That’s Yoakam’s gift at full power: he dignifies ordinary hurt without turning it into theater.

Finally, there’s the matter of place. Yoakam has always written like someone with Kentucky in his bones and California in his stride. “Lonesome Roads” ties those geographies together—front-porch plainness set against West-Coast clarity—so that a three-minute country song can hold an entire map: diners and dim motel lamps, freeway shoulders and empty dance floors, the ache that outlasts the echo. As the last chord falls away, you can almost see taillights disappearing into a stretch of two-lane no one else will drive for you. And somehow, instead of feeling abandoned, you feel understood—which is all most of us ever asked music to do.