A punk confession reborn under honky-tonk lights — “Train in Vain” becomes a bluegrass-tinged handshake between London grit and Bakersfield grace, where denial softens into a rueful smile.

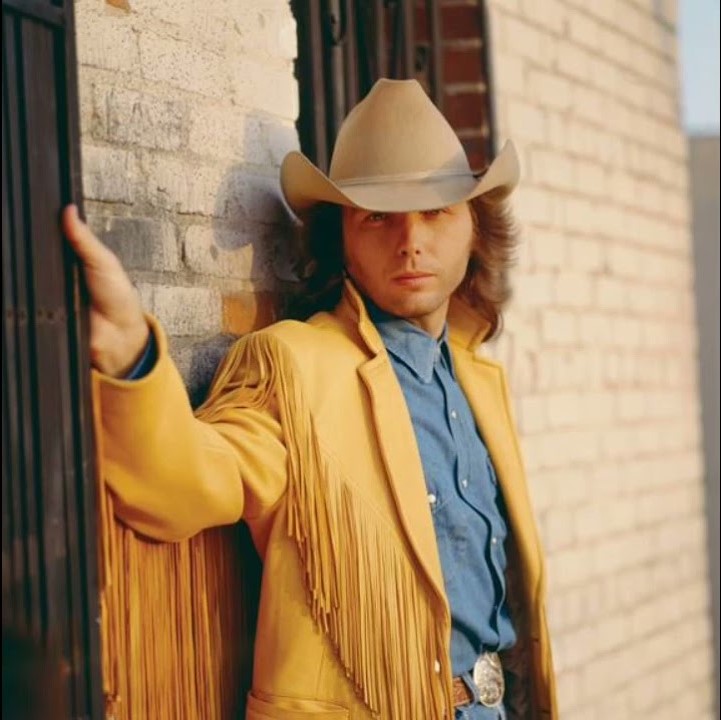

Put the anchors up front, because the facts help memory find its seat. Dwight Yoakam cut “Train in Vain” for his covers set Under the Covers, released July 15, 1997 on Reprise and produced with longtime foil Pete Anderson. It’s sequenced early—track two—as if to say out loud that a country singer raised on Buck and Wynn can love The Clash without blinking. The album itself landed smartly, peaking at No. 8 on Billboard’s Top Country Albums and No. 92 on the Billboard 200; Yoakam’s “Train in Vain” wasn’t pushed as a single, so it carries no chart line of its own—its life is on the record, and in the rooms where listeners heard a familiar hook come home wearing new boots.

What makes this version glow is the way Yoakam changes the temperature rather than the truth. Where The Clash rode a late-night city pulse, Yoakam lights the tune with bluegrass air and Bakersfield pocket. Producer Anderson keeps the rhythm loping and the Telecasters bright; the surprise is the guest standing at Yoakam’s shoulder—Ralph Stanley, who brings high lonesome harmony (and banjo) like cedar smoke at the edge of the melody. The effect is not novelty but recognition: that the ache at the song’s center—I can’t believe you won’t stand by me—sounds just as true under neon as it does on the East End.

To place the song honestly, you remember the source. “Train in Vain (Stand by Me)” arrived as a last-minute, unlisted hidden track at the end of The Clash’s London Calling (1979), then became their first U.S. Top-30 single, peaking at No. 23 on the Hot 100 in 1980; in the U.K., it wasn’t even released as a single at the time. The subtitle “(Stand by Me)” was added in North America to keep the chorus clear and to avoid confusion with Ben E. King’s standard. That odd birth story—spare track turned secret track turned signature hit—already framed the tune as durable and portable, a melody built to travel.

Yoakam hears that portability and leans into conversation over mimicry. He doesn’t chase Joe Strummer’s clenched snarl or Mick Jones’s rangy hurt; he eases the phrasing until the lyric sits like late-night plain talk. The backbeat walks instead of hurries, steel and fiddle color the corners, and when the chorus blooms, Yoakam’s tenor doesn’t demand sympathy—it confesses. To older ears, that restraint is the point. Time teaches that the hardest part of heartbreak isn’t the explosion; it’s the silence afterward, when you learn how to tell the story without shouting. This reading names that hour and lets it breathe.

There’s a subtle courage in the arrangement, too. Inviting Ralph Stanley into a Clash song is less a stunt than a thesis: that the American mountain voice and a punk-born plea share a bloodline of stubborn feeling. You can hear Stanley’s high harmony ride Yoakam’s vowels like a lantern on a dusk road, and the banjo’s light chatter is the country mirror of the original’s chugging urban groove. It’s the kind of cross-talk older listeners may recognize from AM radio days—lines running between genres because the heart doesn’t care about filing systems.

And yet the meaning remains the same because Yoakam trusts the lyric. You said you’d stand by me; I believed you; now I’m standing alone. The Clash sang it against a backdrop of post-punk London; Yoakam sings it like a kitchen-table inventory after midnight. Different rooms, same bruise. The production keeps the room tidy—no grand key change, no decorative solos—so a half-held consonant or a brief swallow at the end of a line can do more than a drum break ever could. You don’t need fireworks when the truth already has a pulse.

It helps, finally, to hold the moment in 1997 beside the first one in 1980. Back then, “Train in Vain” was the hidden song that unexpectedly opened American radio to The Clash; here, it’s the revealed song that shows how wide Yoakam’s musical map really is. The charts record the frame—Under the Covers making a respectable country and pop showing; the track itself uncharted, by design. The heart records the rest: that a good melody, sung with tact, can cross a continent of styles and still feel like it belongs in your house. Wikipedia

So file Dwight Yoakam’s “Train in Vain” where it quietly shines: an album-cut conversion that doesn’t argue for its right to exist; it proves it—by turning a late-’70s London sigh into a front-porch confession and letting the old ache sound new again.