A Heart’s Quiet Rebellion Against the Boundaries of Time and Desire

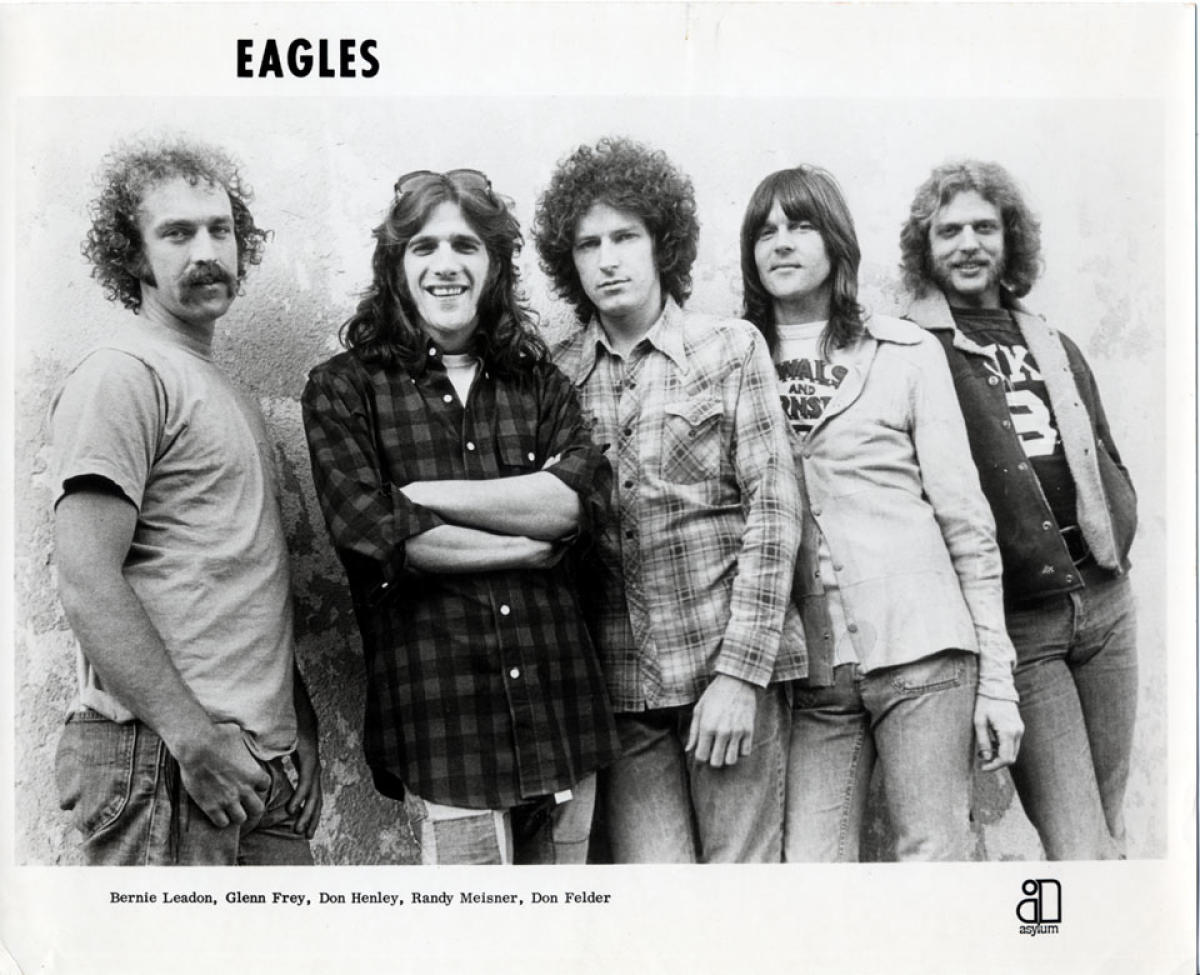

When “Take It to the Limit” was released as a single in November 1975, it climbed to No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100, marking the Eagles’ highest-charting single at that point and further cementing their place at the zenith of 1970s American rock. Featured on their landmark album One of These Nights, the song stands as one of the few in the band’s catalog where bassist Randy Meisner takes lead vocals—a decision that imbued it with a unique vulnerability and longing that no other voice in the group could have delivered quite so achingly.

To understand the emotional weight of “Take It to the Limit”, one must view it not merely as a radio hit or a staple of classic rock playlists, but as an existential soliloquy from a man confronting the twilight between youthful dreams and the sobering gravity of adult limitations. Co-written by Meisner, Don Henley, and Glenn Frey, the song emerged during a period when the Eagles were navigating internal tensions and personal fatigue—a reflection of both the pressures of success and the toll exacted by years on the road.

The lyrics drift like a midnight monologue whispered behind closed doors: “You can spend all your time making money / You can spend all your love making time.” These are not lines written for bravado or escapism; they are quiet reckonings with life’s unrelenting trade-offs. Meisner’s voice, soaring on the repeated crescendo of “take it to the limit one more time,” doesn’t project confidence—it pleads. There is exhaustion here, yes, but also defiance: a weary soul refusing to yield entirely to compromise.

Musically, the track fuses orchestral grandeur with soft rock restraint. The lush arrangement—layered with strings and padded harmonies—provides a cinematic backdrop for Meisner’s vocal arc, which begins introspectively and ends in near-operatic desperation. The song is built around emotional escalation rather than structural complexity; its power lies in repetition that feels increasingly necessary, as if speaking the words over and over might will them into truth.

What sets this song apart in the Eagles’ catalog is its intimacy. Unlike Henley’s often acerbic delivery or Frey’s smooth detachment, Meisner sings like someone trying to convince himself. The final high note he hits—sometimes reluctantly in live performances—became symbolic not only of artistic excellence but also of personal struggle. That note wasn’t just musically demanding; it was emotionally exposing.

In hindsight, “Take It to the Limit” functions almost as Meisner’s farewell letter to the dream-chasing ethos of 1970s rock stardom. He would leave the band just two years later. Yet in this song remains his indelible mark: a beautifully fractured reminder that sometimes our most powerful moments arise when we are closest to surrendering—but don’t.