A Snarling Rebellion Set to Rhythm: When Rock and Roll Found Its Roar

When Elvis Presley unleashed “Hound Dog” in July 1956, the world was not prepared for the seismic shift it would trigger. Propelled by Presley’s incendiary performance and a snarling vocal swagger that electrified the post-war airwaves, the single soared to No. 1 on the Billboard pop chart, where it reigned for an astonishing eleven weeks. Released on RCA Victor, and later included in the compilation album Elvis’ Golden Records, the song became a cultural thunderclap—a defining anthem of youth rebellion and a pivotal moment in the birth of rock and roll’s mainstream ascension.

But “Hound Dog” did not begin with Elvis. Originally recorded in 1952 by blues singer Big Mama Thornton, the song was penned by the prolific songwriting duo Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, whose sharp, streetwise lyrics told of betrayal, defiance, and female agency. Thornton’s version was a raw, growling blues track—gritty, unvarnished, and infused with Southern pain—that climbed to No. 1 on the R&B charts and stood as a potent expression of womanly rage against a faithless man.

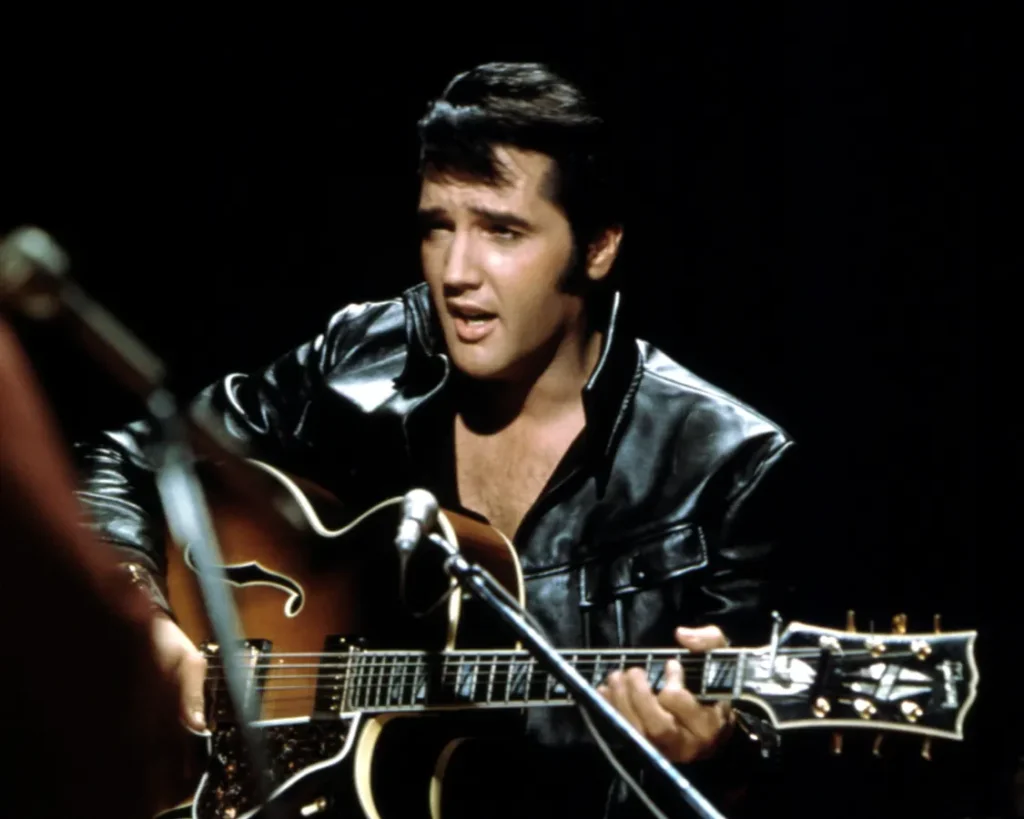

Presley’s interpretation took a radically different tack. Reimagined with a faster tempo and stripped of its original blues phrasing, Elvis transformed “Hound Dog” into a rockabilly explosion. Backed by guitarist Scotty Moore, bassist Bill Black, and drummer D.J. Fontana, his rendition pulsated with youthful urgency—a sonic affront to staid conventions. What had been a woman’s bitter indictment of a cheating lover became something more abstract in Presley’s hands: a euphoric release of attitude, disdain, and sexual bravado. He turned “You ain’t nothin’ but a hound dog” into a universal declaration—dismissive, triumphant, and dripping with cool contempt.

The performance that cemented the song’s mythos came on national television: Presley’s gyrating hips during his appearance on The Milton Berle Show in June 1956 scandalized middle America and thrilled its teenagers. It wasn’t just music—it was movement; it was rebellion incarnate. The performance drew waves of criticism from conservative commentators who saw in it the unraveling of social decorum. But for a generation feeling constrained by Eisenhower-era conformity, it felt like liberation set to rhythm.

Lyrically simple yet brimming with attitude, “Hound Dog” distills rock and roll to its most primal essence: two-and-a-half minutes of blistering vocals over a driving beat that leaves no room for apology or restraint. It is not merely about lost love or wounded pride—it is about asserting control in the face of betrayal; about shedding inhibition; about wielding voice as weapon and shield alike.

In retrospect, “Hound Dog” was more than just a hit single—it was an ignition point. With this track, Elvis Presley didn’t just cover a song; he repurposed it into an anthem for postwar America’s restive youth—a generation yearning to break free from the stifling grip of decorum and forge its own identity in snarls and shouts rather than polite conversation.

To listen today is to hear more than early rock at its peak; it is to witness an epochal shift—when America first heard its children howl back at tradition through a young man from Tupelo who dared to sing like every rule had already been broken.