“I Ain’t Never” in John Fogerty’s world is a grin with a bruise beneath it—country mischief on the surface, and a man quietly rebuilding his musical identity underneath.

Let’s put the pillars of truth first. “I Ain’t Never” was co-written by Mel Tillis and Webb Pierce, and it already had a storied life before John Fogerty ever touched it. Webb Pierce cut the song in 1959, taking it to No. 2 on Billboard’s Hot C&W Sides and even crossing it over to No. 24 on the Billboard Top 40—a rare double victory for a honky-tonk single in that era. Years later, Mel Tillis re-recorded it and scored his first No. 1 on Billboard Hot Country Singles in 1972 (also No. 1 in Canada).

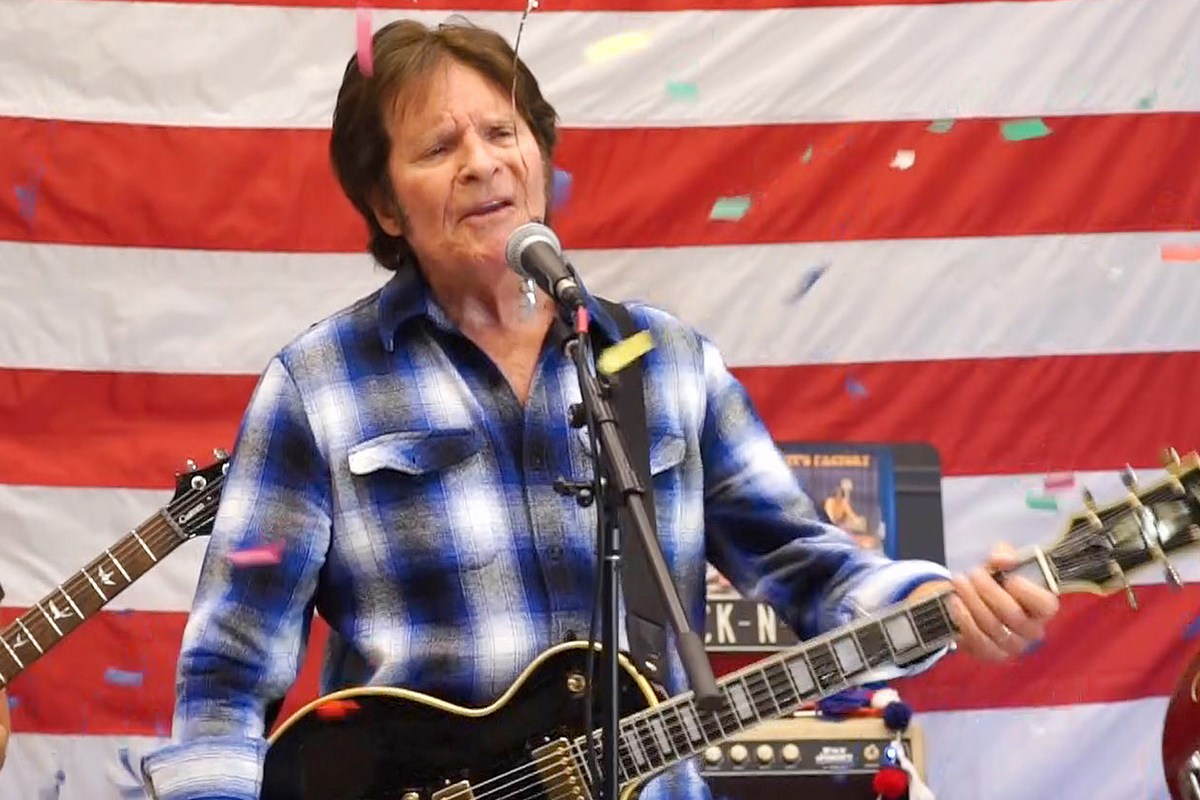

Fogerty’s version arrives from a very particular crossroads: it appears on his 1973 album The Blue Ridge Rangers, released April 1973, an album credited to “The Blue Ridge Rangers” with no mention of Fogerty on the original cover. Even more striking, Fogerty played all the instruments himself—an almost stubborn one-man-band choice that feels like both retreat and reinvention. The album peaked at No. 47 on the Billboard 200, making it a modest success—quietly impressive for a record that deliberately downplayed the famous name behind it.

Now, what does it feel like?

If you come to “I Ain’t Never” expecting the swampy bite of Creedence—those back-porch riffs that sounded like American history sweating under a streetlight—you’ll notice something different immediately. This is Fogerty stepping out of the preacher’s pulpit and into the dancehall, trading prophecy for punchline. The lyric is classic country comedy-drama: a lover who vanishes, a landlord who shrugs, a narrator left blinking at the absurdity of it all—and still loving her “just the same.” It’s the oldest kind of heartbreak: the kind that doesn’t get a grand explanation, only a story you tell your friends with a laugh that’s trying not to crack.

But the real story behind Fogerty’s recording isn’t only in the lyric—it’s in the career moment. The Blue Ridge Rangers was released after the end of Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Fogerty chose the anonymous band-name credit specifically to distance himself from his legacy. That’s not just a marketing quirk; it’s a psychological snapshot. Imagine being recognized everywhere for a voice that defined an era, then choosing—almost defiantly—to step sideways into old country standards and traditional material, as if to say: Before I’m “John Fogerty the icon,” I’m still a musician who loves songs.

In that light, “I Ain’t Never” becomes more than a cover. It’s a mask with meaning. It lets Fogerty inhabit a character who’s been outfoxed by love, but who keeps his dignity by keeping his humor. And isn’t that, in its own way, a survival tactic? Sometimes the only way to carry disappointment is to turn it into rhythm—two-stepping right over the bruise and calling it a dance.

There’s also something intimate—almost monastic—about the fact that Fogerty played everything himself on the album. With “I Ain’t Never,” you’re hearing not only a performance but a private workshop: one man in a studio, reaching back to earlier American music as if it were a set of tools laid out on a bench. Country, gospel, bluegrass—these aren’t costumes here. They’re the roots under the roots.

So when John Fogerty sings “I Ain’t Never,” you can enjoy it for what it is—a lively, time-tested country narrative with a hook that refuses to die. But if you listen a little longer, you’ll hear the deeper tenderness: a famous voice choosing humility, choosing tradition, choosing to disappear into the song rather than stand above it. In the end, that may be the most moving “twist” of all—Fogerty, at a moment when he could have chased his own legend, instead going back to a simpler promise: let the song speak, and I’ll follow where it leads.