A Quiet Lament of Love Lost, Echoing Through the Smoke of Memory

When Willie Nelson released his version of “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” in 1975, it marked not only a career resurgence but also a seismic shift in the cultural perception of country music. Featured on the seminal concept album Red Headed Stranger, the track became Nelson’s first No. 1 hit as a solo artist on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, quietly announcing that something different—something deeply human and profoundly poetic—was stirring beneath the polished surface of Nashville’s commercial sound.

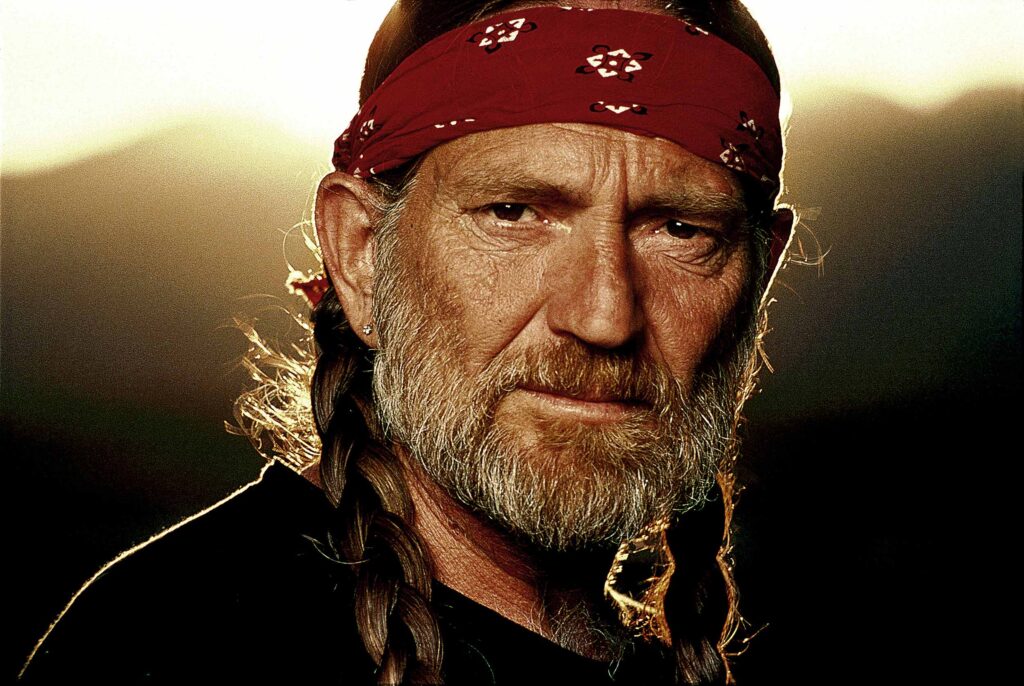

Originally penned by Fred Rose in 1945 and recorded by artists like Roy Acuff and Hank Williams Sr., “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” had long lingered in the periphery of country tradition. But in Nelson’s hands, it transcended mere interpretation; it became an elegy. Stripped of ornamentation, bathed in sparse acoustic guitar and ghostly piano lines, Nelson’s rendition transformed the song into a hymn for the heartbroken and a meditation on love’s impermanence. His weathered voice—soft, cracked, almost whispered—didn’t so much sing the lyrics as breathe them into life, each phrase trailing off like smoke curling from a dying fire.

At its core, the song is an exercise in restraint—a minimalist canvas upon which emotion is painted with broad but delicate strokes. The narrator walks away from a final goodbye beneath weeping skies, clinging to one last image: blue eyes crying in the rain. Yet within that simple tableau lies a lifetime’s worth of sorrow and reflection. The song speaks not only to romantic parting but to existential grief—the way love decays not through betrayal or anger, but through time and mortality.

Nelson recorded “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” as part of Red Headed Stranger, a concept album telling the story of a fugitive preacher haunted by loss and driven by vengeance. Within this narrative arc, the song serves as an emotional fulcrum—the moment when sorrow eclipses rage, when remembrance overtakes narrative momentum. It is here that Nelson fuses character and self, his own stoic melancholy aligning perfectly with the lonesome pastor he embodies.

Musically, the track defies mid-70s country conventions. There are no string sections or backing vocals to cushion its emotional weight. Instead, there’s space—vast and unrelenting—which allows each note to hang suspended, each silence to throb with unresolved pain. This starkness became a hallmark of what would later be dubbed “outlaw country,” a movement that rejected studio gloss in favor of raw authenticity.

But even beyond genre or era, “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” endures because it understands something fundamental: that memory is both sanctuary and prison. Nelson doesn’t merely recount a lost love; he relives it with every aching syllable. The song is not about mourning loudly—it’s about mourning endlessly.

And so it lingers—not just as Willie Nelson’s breakthrough hit or as a cornerstone of outlaw country—but as one of American music’s most intimate portrayals of grief: honest, unadorned, and devastatingly real.