“Hard Times (Hard Crimes)” is a TV-theme-sized confession: a man trying to stay decent while the job asks him to disappear into danger—and come back unchanged.

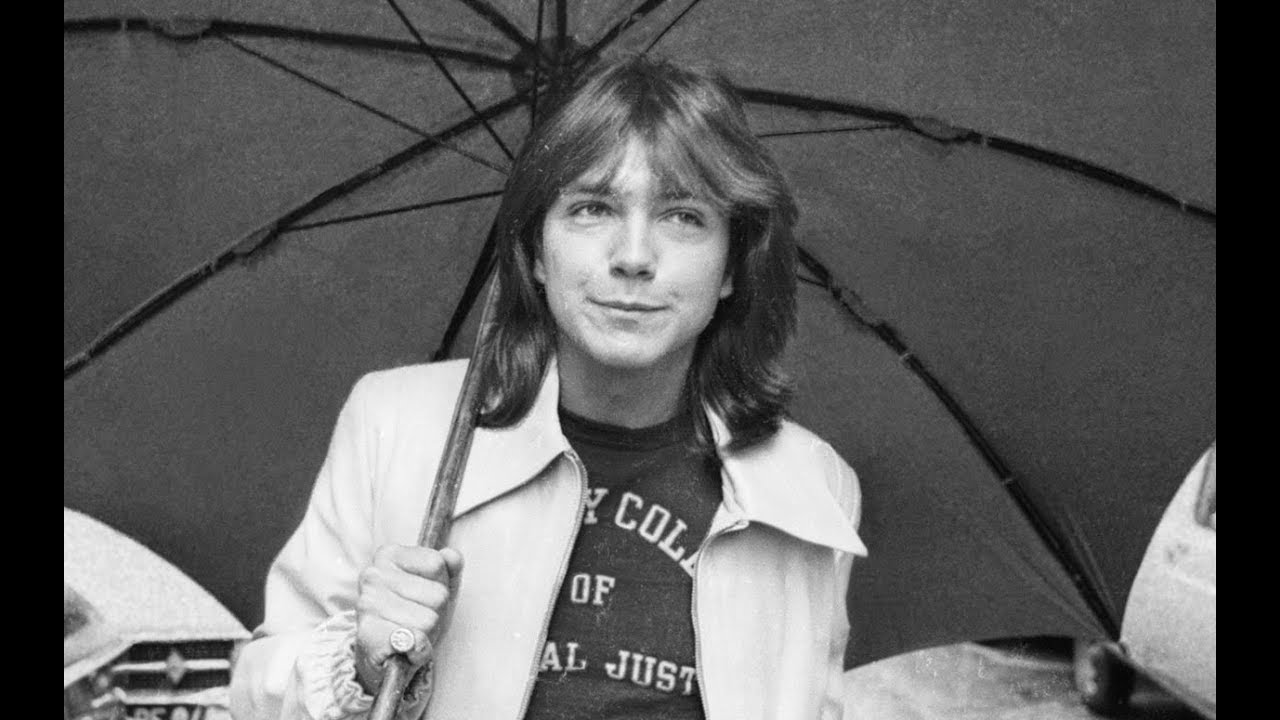

What you’re hearing under the title “Hard Times (Hard Crimes)” is one of those fascinating “almost-songs” that carry more emotional weight than their running time suggests. It’s best known as the opening theme for David Cassidy: Man Undercover, the short-lived NBC series that ran from November 2, 1978 to July 12, 1979 and aired ten episodes before it was cancelled. The show itself was built around an image-shift that felt bold at the time: David Cassidy—so strongly associated with pop stardom—playing undercover cop Dan Shay, infiltrating youth crime with the uneasy knowledge that you can’t live in disguise without paying for it.

The song’s identity is a little slippery, and that’s part of its story. You’ll see it labeled as “Hard Times,” “Hard Times, Hard Crimes,” or “Man Undercover (Hard Times, Hard Crimes).” The most reliable through-line is authorship: Cassidy co-wrote it with Jay Gruska. The official site is unusually candid about what fans have long suspected: a full version was recorded, but it was never commercially released—only part of it was used as the TV theme. That detail changes how the music feels. You’re not just listening to a “jingle” engineered to get you to the first scene; you’re hearing a cut-down fragment of something that wanted to be a proper pop record—something with verses that breathe, with a moral argument inside it.

And the argument is right there in the lyric: Love is a child… warm like the smile…—a domestic, tender image—followed by the cold snap of reality: the life “out on the street” is a fight, and you face it every night. In the chorus, the question lands like a bruise you keep pressing to see if it still hurts: “Whose soul are you saving?” and, just as painfully, “Are they saving anything for you?” For a theme song, it’s almost shockingly philosophical. It doesn’t flatter the hero; it doubts him on his behalf. It suggests that doing the “right thing” can still take a piece out of you, quietly, until you start to wonder what part of you is left unborrowed.

There’s also an important, often-missed footnote in the credits conversation: several reputable TV-reference sources note that the show’s music was associated with composer Harry Betts, while the title song is performed by Cassidy. That makes sense in practical terms—television frequently separates “score composer” from “theme/songwriters”—and it helps explain why the theme feels like it sits between worlds: part pop statement, part dramatic warning label.

As for chart history: there isn’t one, at least not in the way you’d expect from Cassidy’s early-’70s run. This theme was planned as a single in its full form (according to fan-archived documentation), but it never came out as a commercial 45. Its afterlife has been more like a whisper passed between collectors. A short edit (about a minute) surfaced on the 1990s TV-theme compilation Tube Tunes Volume Two: The ’70s and ’80s, which includes “Hard Times (Hard Crimes)” credited to Cassidy.

The deeper “behind-the-scenes” story is really Cassidy’s own. The series itself spun out of his dramatic turn as officer Dan Shay in the Police Story episode “A Chance to Live,” a performance that Wikipedia notes earned him an Emmy nomination—a striking counter-narrative to the idea that he was only ever a teen idol. So when he sings “Hard Times (Hard Crimes)”, it doesn’t come off like an actor dutifully selling a show. It comes off like someone trying to announce a new adulthood—and doing it in the most vulnerable way possible, by asking whether the work that makes you “necessary” might also make you lonely.

That’s why the song lingers. It isn’t Christmas nostalgia or chart nostalgia. It’s moral nostalgia: that old, bruised belief that you can enter the dark for the right reasons and still return to the light without losing your name. The theme’s greatest trick is that it doesn’t guarantee that outcome. It simply keeps the porch light of the chorus burning and asks—again and again—how much a person can carry before the disguise becomes the face.