“Sailor’s Lament” is CCR’s sea-mist meditation on restlessness – a song where the horizon keeps calling, even when you already know what it costs to follow it.

Creedence Clearwater Revival recorded “Sailor’s Lament” as track 2 on Pendulum, released by Fantasy Records on December 9, 1970—a crucial late-period CCR album that still reached No. 5 on the Billboard 200. The song runs 3:47 and is credited, like most of the record, to John Fogerty. And while “Sailor’s Lament” itself was never the headline single in the U.S., the album’s lone major single pairing, “Have You Ever Seen the Rain” / “Hey Tonight,” arrived in January 1971 and climbed to No. 8 on the Billboard Hot 100—a reminder of how much popular force CCR still carried at the turn of the decade.

But “Sailor’s Lament” doesn’t feel like it was written for charts. It feels written for the hours when the house is quiet, when the day’s noise finally drains away and a different kind of sound rises—an inner tide, pulling at the ribs. Even the title tells you this isn’t the band’s usual swamp-stomp or back-porch sermon. A “lament” is older than rock radio. It belongs to folk songs, work songs, hymns sung softly enough that only the faithful can hear. CCR borrow that gravity and keep it in motion, turning it into something you might imagine rolling out of a coastal bar at last call: the narrator half-brave, half-beaten, staring at the black water and wondering whether leaving is freedom… or just another way of losing.

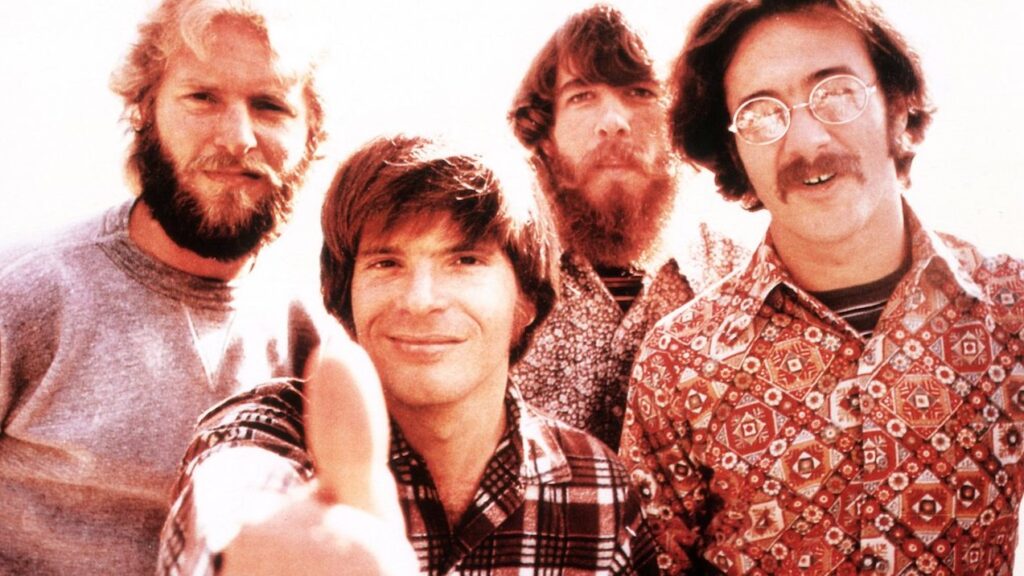

Part of what makes the track so haunting is its placement in Pendulum—an album made under pressure, recorded at Wally Heider Studios in San Francisco in November 1970, and reportedly taking longer than usual for the band. By then, CCR were a machine that could stamp a hit into the grooves almost on command, but the machine was starting to rattle. A pre-session band meeting had seen Tom Fogerty, Stu Cook, and Doug Clifford pushing for more creative input from John Fogerty, the band’s dominant writer and arranger. When you listen to “Sailor’s Lament” with that context in mind, it starts to sound like more than a maritime story. It becomes a small allegory about control and drift—about what happens when people who once moved as one begin to feel pulled by different currents.

Musically, Pendulum is often remembered as the record where CCR widened their palette—more keyboards, more color in the rooms of the songs. “Sailor’s Lament” benefits from that expanded air. It doesn’t rush like a chase scene; it travels like a vessel cutting through dark water—steady, determined, with a hint of unease underneath the rhythm. It’s a Fogerty performance that feels less like a barked command and more like a confession measured carefully, as if saying the truth too loudly might make it real.

And then there’s the song’s quiet afterlife—almost as private as the lament itself. In at least some territories, “Sailor’s Lament” appeared as the B-side to an international single release of “Molina,” a pairing that makes perfect sense: one track swaggering under streetlights, the other looking outward toward the sea. Collector notes also report that CCR never performed “Sailor’s Lament” live, which only deepens its aura as an “album-inner” song—meant for the listener’s solitude rather than the crowd’s roar.

What does it mean, really—this sailor’s ache?

It’s the feeling of being unable to stay still in your own life. The narrator’s voice carries that old contradiction: longing for home, longing for away, and suspecting that whichever one you choose will break your heart in a different way. The sea becomes a metaphor for the part of us that can’t be domesticated—the part that hears the same old conversation, the same old room, and suddenly feels the walls narrowing. In that sense, “Sailor’s Lament” isn’t only about waves and distance. It’s about identity. About the quiet fear that the person you’re supposed to be—steady, loyal, rooted—might not be the person you are.

That’s why the song still lands like weather. It doesn’t depend on fashion. It doesn’t need a chorus that kicks down a door. It simply tells the truth in a low voice: that some hearts are built like ships—beautiful, functional, and never completely at rest. And when Creedence Clearwater Revival sing it, you can almost hear the larger, unspoken story behind the notes: a great band still moving forward, still charting high, yet already feeling the first cold draft of an ending somewhere out past the lights.