A Storm-Born Hymn of Southern Grit and Mysticism

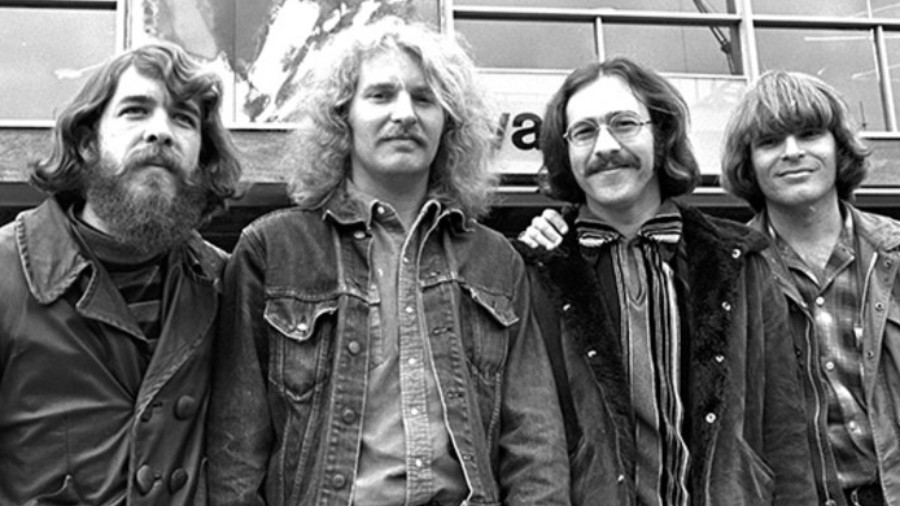

In the raw, rain-soaked landscape of late-1960s American rock, Creedence Clearwater Revival emerged like a preacher in a lightning storm—urgent, elemental, and undeniable. “Walking on the Water,” released in July 1968 on their self-titled debut album Creedence Clearwater Revival, stands as one of the band’s earliest compositions that fused swampy blues-rock with a mythic, Southern Gothic sensibility. Though it was not released as a single and never charted independently, its presence on the LP revealed the depth of John Fogerty’s songwriting vision—a vision that would soon define the sound of American roots rock for decades to come.

Unlike many of their contemporaries who relied on psychedelia or polished pop structures, CCR built their reputation on stripped-down power and storytelling steeped in biblical imagery, bayou folklore, and working-class longing. “Walking on the Water”—co-written by John and Tom Fogerty—is a testament to that emerging identity, a song that doesn’t just play—it smolders, evokes, and haunts.

Origins and Early Sound

The song’s roots predate the band’s transformation into Creedence Clearwater Revival. Originally performed by their earlier incarnation, The Golliwogs, in 1966, “Walking on the Water” was one of the first compositions where John Fogerty began asserting creative dominance. Re-recorded for their 1968 debut, the track was sharpened with a newfound clarity and menace: thick guitar distortion, ominous vocal delivery, and a rhythm section that moved like a restless tide.

By the time it appeared on Creedence Clearwater Revival, the band had fully shed their earlier identity and donned the mantle of musical conjurers—channeling Delta blues, Memphis soul, and backwoods mythology through the haze of California garages. This song in particular hinted at what was coming, both thematically and sonically. If later hits like “Born on the Bayou” or “Run Through the Jungle” painted expansive landscapes of the American South, “Walking on the Water” was the flicker of candlelight before the storm.

Lyrical and Thematic Depth

The lyrics of “Walking on the Water” drip with mystery and religious symbolism, invoking the image of a man who defies natural law—a miracle worker, perhaps, or a prophet. But there’s no triumph in Fogerty’s voice—only awe and a tinge of fear. The repeated phrases—“I saw you walking on the water”—are delivered not with reverence, but with a sort of bewildered anxiety. It’s a song less about faith and more about the unknowable power some people carry within them.

This biblical allusion—referencing Christ walking on the Sea of Galilee—serves as metaphor rather than sermon. In Fogerty’s world, miracles aren’t salvation; they’re disruptions. The man who walks on water isn’t necessarily a savior—he’s a force to be reckoned with, a figure out of myth that threatens to overturn the natural order. As such, the song becomes a parable about power, otherness, and the mystery at the heart of human experience.

Musical Atmosphere and Legacy

Musically, “Walking on the Water” is steeped in menace. The track opens with a murky guitar riff, drenched in reverb, like the first rumble of thunder in a summer storm. Fogerty’s voice is rasped and urgent, full of the dark charisma that would define him. Doug Clifford’s drumming is restrained but relentless—like footsteps on a wooden dock at midnight. And Stu Cook’s bassline rolls beneath it all with a sense of dread that never quite resolves.

Though never a radio staple, the song earned its place as a fan favorite and a live set staple in CCR’s early days. More importantly, it laid the thematic and sonic groundwork for the band’s breakthrough in 1969. Songs like “Bad Moon Rising” and “Green River” would refine the formula, but “Walking on the Water” was one of the earliest glimpses into the dark river Fogerty was already navigating—where gospel met gumbo, and rock ’n’ roll became something primal again.

In retrospect, “Walking on the Water” feels less like a song and more like an incantation—an early chapter in the Creedence gospel, echoing from the edge of the swamp. It reminds us that even before the hits, before the festival stages and the Vietnam-era anthems, CCR was already tapping into something older, stranger, and deeply American: the sound of myth rising up from the mud.