“Do You Believe in Magic” is a reminder that music can still unlock the younger heart—without pretending we’re young again

There’s a particular kind of joy that doesn’t feel like “happiness” so much as release—the moment a familiar rhythm loosens the knots in your chest, and you remember who you were before life taught you to brace yourself. That is the promise tucked inside “Do You Believe in Magic”, written by John Sebastian and first released in 1965 by The Lovin’ Spoonful—a debut single that rose to No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100. The song’s genius has always been simple: it doesn’t preach or analyze; it just points to a truth most people learn the long way—that music can change the temperature of a room, and sometimes the temperature of a life.

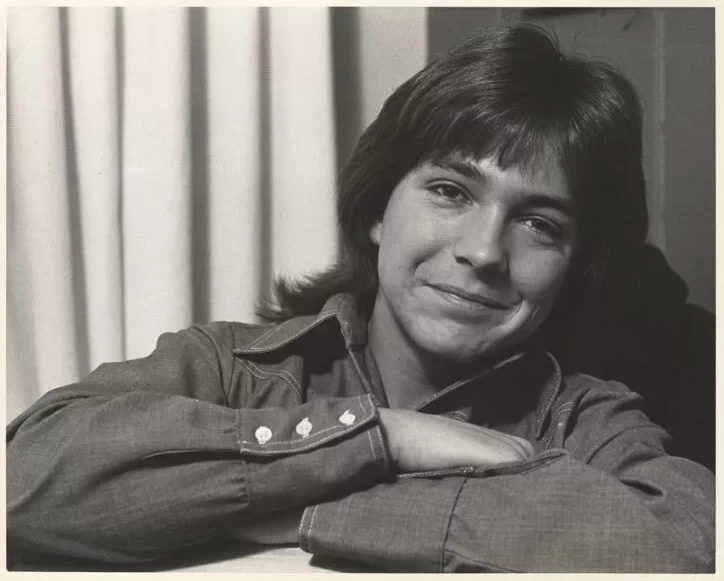

When David Cassidy recorded “Do You Believe in Magic” decades later, he wasn’t trying to compete with the bright snap of 1965. He was doing something subtler: returning to the idea of “magic” from the far side of experience. His studio recording was made for Then and Now, a career-spanning compilation released in the UK on October 1, 2001, and in the US on April 30, 2002. On the US edition in particular, “Do You Believe in Magic” is described as a new recording included in the track list—one tied to a moment of pop culture warmth that many people still remember with a small, unexpected fondness: Cassidy had also performed the song in a Mervyn’s Christmas television advertisement.

The chart “headline” here belongs not to the single, but to the album that carried it. In the UK, Then and Now entered the Official Albums Chart on 13 October 2001, and reached a peak of No. 5 on 20 October 2001. That matters because it tells you what kind of return this was: not a nostalgic footnote, but a genuine re-connection—an audience meeting an old voice again, and finding it still capable of touching something honest.

What makes Cassidy’s choice of “Do You Believe in Magic” so poignant is the contrast between lyric and life. The song is famously youthful—“in a young girl’s heart”—yet its deeper meaning has never been about age. It’s about the sudden freedom music can offer “whenever it starts,” like a door opening where you didn’t know there was a door. Cassidy, who spent much of his life navigating the strange bargain of fame—adoration that can feel both tender and trapping—understands that kind of freedom in a uniquely personal way. In his hands, the song becomes less a teenage rush and more a gentle proof: the spark still works.

And then there’s the tone of it—the way a late-career recording can carry a different kind of light. The original Lovin’ Spoonful version is quick and buoyant, built like a bright little engine. Cassidy’s recording, by context alone, lands differently. It lives inside a project literally titled Then and Now—a name that invites comparison, memory, and the soft ache of time passing. So when he sings about music “freeing” the heart, the line doesn’t sound like an abstract ideal. It sounds like someone acknowledging, quietly, how rare it is to feel unburdened—and how precious it is when a simple song manages to do it anyway.

The “story behind” this track isn’t a scandal or a chart battle. It’s something more human: a voice from one era stepping gently into another, carrying a beloved 1965 pop spell into the early 2000s, and letting it mean what it’s always meant—only now with more history in the room. Cassidy’s “Do You Believe in Magic” belongs to those recordings that don’t demand you dance, but make it hard to stay completely still. It reminds you of car radios, of seasonal commercials that unexpectedly tugged at the heart, of melodies that feel like old friends showing up at the door without warning.

In the end, the magic here isn’t a trick. It’s recognition. David Cassidy doesn’t have to rewrite the song’s message; he just has to stand inside it. And when he does, “Do You Believe in Magic” becomes what the best pop songs become over time: not a relic, not a rerun, but a small, stubborn candle—still burning, still warm, still capable of making the past feel close enough to touch.