A Psychedelic Riff on Loneliness and Liberation in the Twilight of Love

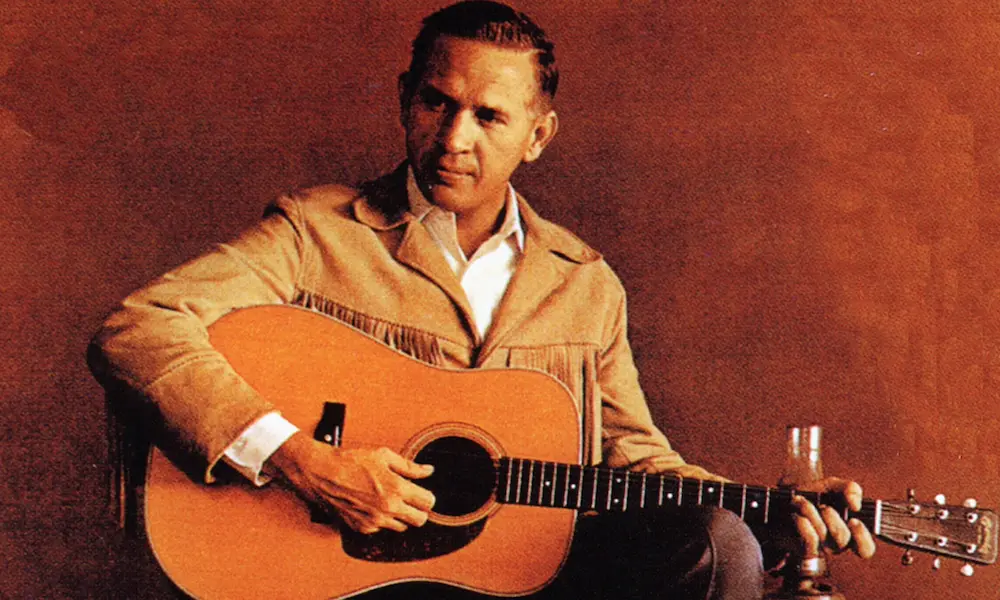

When Buck Owens released “Who’s Gonna Mow Your Grass” in late 1969, it marked a bold moment of stylistic expansion for one of country music’s most defining figures. Issued as a standalone single before later appearing on the 1970 compilation album “The Kansas City Song,” the track climbed to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles chart, reaffirming Owens’ commercial dominance even as he pushed against the traditional boundaries of the Bakersfield Sound he helped pioneer.

At first blush, the song’s title might suggest a simple, rustic musing—perhaps a tongue-in-cheek lament about the practicalities of domestic life. But within its deceptively plainspoken phrasing lies a deeper emotional terrain. What begins as a question about lawn maintenance unfurls into a meditation on abandonment, pride, and the uneasy marriage between independence and regret. It is a country song in classic form—rooted in vernacular simplicity—but adorned with unexpected textures that hint at broader cultural currents and personal uncertainty.

Musically, “Who’s Gonna Mow Your Grass” is one of Owens’ most experimental moments—a daring blend of honky-tonk twang and acid-tinged guitar fuzz that bordered on psychedelic. The lead electric guitar line, distorted and bent at odd angles, caused more than a few eyebrows to arch when it hit airwaves. Longtime fans accustomed to the clean lines and crisp arrangements of Owens’ earlier work may have felt jarred by this sonic departure. Yet it was precisely this fusion of styles—the barroom realism of country colliding with the era’s headier tones—that gave the song its enduring edge. The juxtaposition underscored the emotional dissonance at its heart: yearning wrapped in sarcasm, heartbreak cloaked in irony.

Lyrically, Owens crafts a narrative that is both specific and universal. “You’re actin’ mighty brave / But I can tell you miss me by that faraway look in your eyes,” he sings with a blend of resignation and reproach. The lyrics imply a partner walking away—perhaps emboldened by newfound independence or seduced by fantasies beyond their rural life—but Owens’ narrator remains rooted in pragmatic reality: someone still has to mow the lawn. It’s an ingenious metaphor for all the taken-for-granted roles people play in relationships—the quiet labors of love that go uncelebrated until they are gone.

In many ways, “Who’s Gonna Mow Your Grass” anticipated country music’s coming shift—a foreshadowing of the genre’s eventual embrace of more expansive themes and modernist production techniques. And yet it remains unmistakably grounded in Buck Owens’ legacy: sharp-eyed, emotionally resonant, laced with wit but never frivolous. It is both an artifact of its time and a timeless expression of post-love reckoning—where anger gives way to melancholy, and beneath every sarcastic jab lies the ache of something lost.