“Blueboy” is John Fogerty smiling through the swamp-mist—an ode to the kind of back-road music that keeps a town breathing when nothing else will.

If you want the hard facts up front, they tell a very specific story: “Blueboy” is track three on John Fogerty’s 1997 comeback album Blue Moon Swamp (released May 20, 1997). When rock radio began to embrace it, the song appeared on Rock Airplay Monitor’s Heritage Rock chart dated October 3, 1997 (covering the week September 22–28, 1997) at No. 15. Around the same period, the commercial single release “Blueboy / Bad Bad Boy” is listed by AllMusic with a release date of October 7, 1997. And while it wasn’t a pop crossover, it did register in the rock world: Fogerty’s discography lists “Blueboy” peaking at No. 32 on Billboard’s Mainstream Rock chart.

Those numbers matter, because they frame “Blueboy” not as a nostalgia act, but as a living, breathing late-’90s rock record—one that carried Fogerty’s unmistakable fingerprints while still sounding at home beside the era’s airplay rhythms. Blue Moon Swamp itself wasn’t just warmly received; it was officially honored, winning Best Rock Album at the 40th Annual GRAMMY Awards. And “Blueboy”—of all songs—was singled out for attention too, earning a nomination for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance (1998 GRAMMY year).

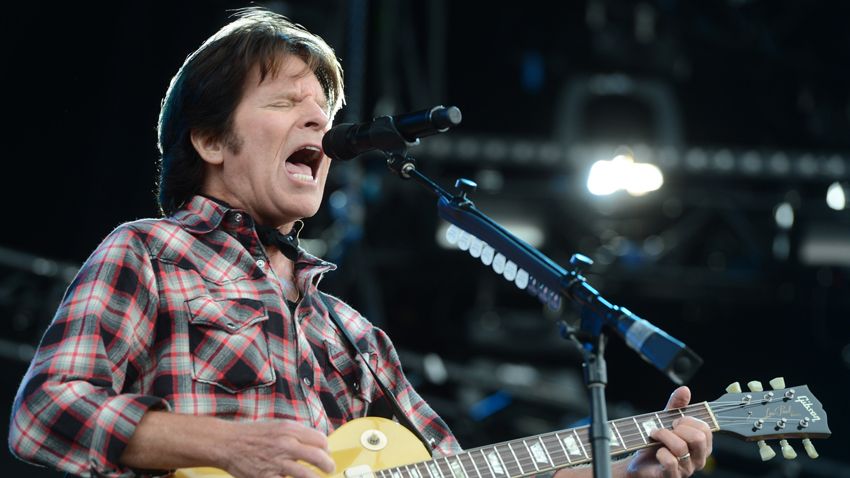

What makes that nomination feel fitting is how human the performance is. Fogerty doesn’t sing “Blueboy” like a stadium sermon. He sings it like a story traded across a table—simple details, warm lighting, the sense that the room is full even if the world outside is empty. The lyric sketches an old hillside place where people travel “from miles around” to watch a certain Dooley do his show, and the refrain becomes a kind of communal permission slip: let the blueboy play. You can hear the song grinning at the idea that sometimes, the most important thing a person can do is keep the music going—because the music is what keeps the people from going home too early, from closing up their hearts, from surrendering the night to silence.

Behind the curtain, there are lovely, concrete touches that deepen the picture. “Blueboy” is noted as the only Fogerty recording to feature bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn, and its backing vocals were provided by The Waters—a combination that quietly roots the track in American soul and gospel-rock tradition, without ever turning it into pastiche. Fogerty also leaned into a deliberately vintage guitar shimmer—using a Danelectro and a 1962 brown Concert amplifier to get that tremolo pulse that feels like heat rising off pavement. Even the song’s visual afterlife stays close to the ground: a music video released in summer 1998 places him at a laid-back country barbecue, with his wife Julie on tambourine and their sons in the crowd—less “rock god,” more “the music belongs to the family table.”

In that sense, “Blueboy” is a small masterpiece of mood. It romanticizes a local hero—a player, a vibe-setter, someone who turns an ordinary patch of earth into a destination. But it’s not naïve romance. There’s an undertow of something older: the awareness that people need places like this, and need songs like this, because life doesn’t always offer grand solutions. Sometimes it offers a Friday night, a familiar riff, and the mercy of being among others who understand the same rough weather.

Listen closely and you’ll notice how Fogerty builds the meaning without preaching it: the “blueboy” isn’t just a musician; he’s a symbol of what music does at its best—turning hardship into motion, turning loneliness into attendance, turning “going home” into “staying one more song.” And when that chorus returns—“let the blueboy play”—it lands like a gentle commandment for anyone who’s ever been saved, even briefly, by a band in the corner and a tune that made the world feel less heavy.