“Dos Arbolitos (Two Little Trees)” is a tender parable of companionship—two “twin” trees leaning toward each other as life teaches that even strength longs to be shared.

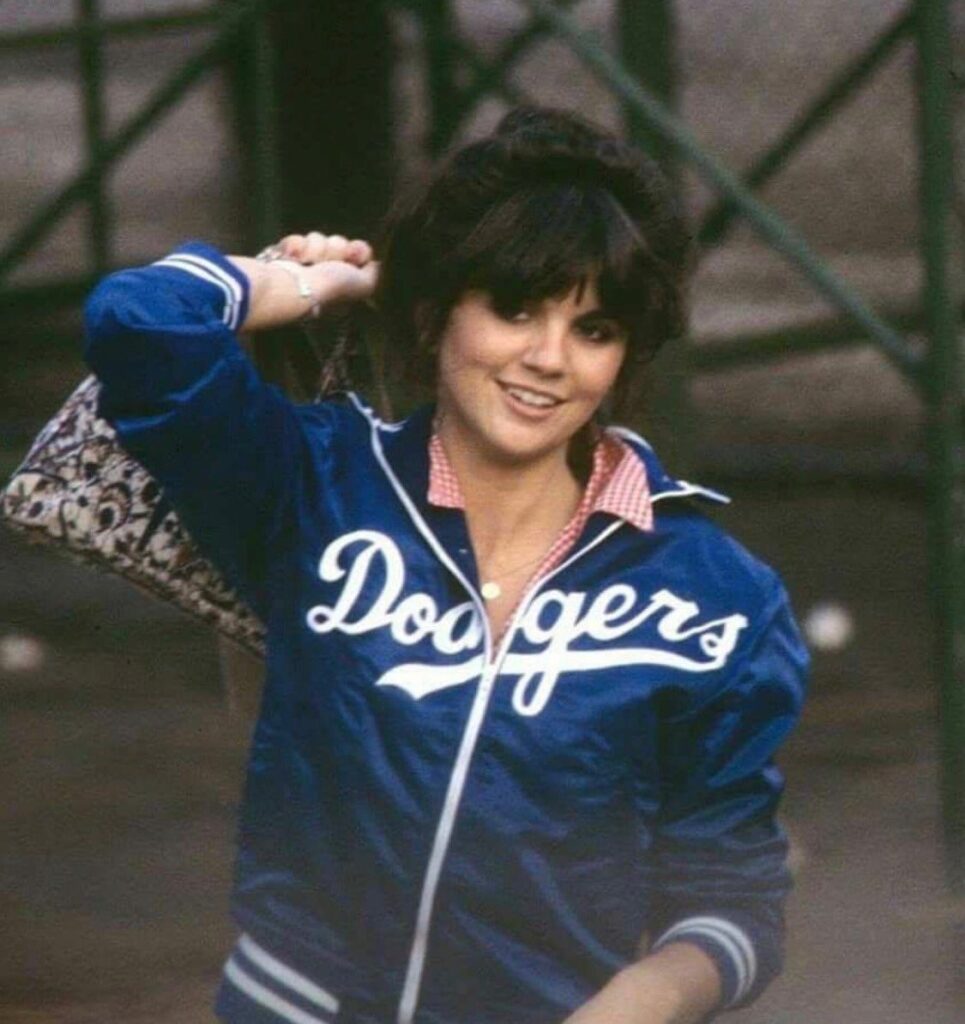

In November 1987, Linda Ronstadt did something that still feels quietly brave: she stepped away from the English-language pop throne she had built and walked straight into the songs that raised her at home. That step produced Canciones de Mi Padre—a mariachi and ranchera album rooted in family memory, released on Elektra/Asylum, and it landed with a kind of astonishment. In the U.S. it reached No. 42 on the Billboard 200, an extraordinary peak for a Spanish-language mariachi record in the mainstream album marketplace. The project went further than “respectable”: it won a Grammy, went double platinum, and became widely recognized as the best-selling non-English language album in American history—a cultural moment, not just a release. Later honors only confirmed its weight: the album was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame (announced in 2021) and selected for preservation in the Library of Congress National Recording Registry in 2022.

Inside that landmark album sits “Dos Arbolitos (Two Little Trees)”, credited to Mexican composer Chucho Martínez Gil. Ronstadt didn’t release it as a charting pop single, but it did have a small, telling “marketplace life”: in 1988, “Dos Arbolitos” appeared as the B-side to “Tú Solo Tú” on a 7-inch vinyl release—almost like a secret pressed into the record for anyone willing to turn it over and listen closely.

What makes “Dos Arbolitos” linger, though, is not any ranking. It’s the image at its center—so simple it feels inevitable, so gentle it disarms you before you realize you’re moved. The lyric begins with a scene you can practically see: two little trees were born on my ranch, “like twins,” visible from the singer’s small house beneath the “light of heaven.” They are never separated; their branches “caress” one another, “as if they were lovers.” And then, without raising its voice, the song turns into a human confession: beneath that shade, the singer waits—tired, thoughtful—asking the sky for a companion.

That is the quiet genius of this song: nature is not decoration here. Nature is evidence. Two trees become proof that closeness is not weakness, that leaning is sometimes simply the shape of being alive.

Ronstadt’s performance amplifies that meaning because of where it sits in her story. The Library of Congress essay about Canciones de Mi Padre describes how she grew up singing Mexican songs with her family on Sunday afternoons, her father playing records as everyone sang along—music as household language, not “genre.” Recording the album, the essay notes, became a collaboration with arranger/producer Rubén Fuentes—a key figure associated with Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán—and a broader all-star gathering of mariachi musicians, shaped by Ronstadt’s insistence on honoring the older, simpler spirit she remembered from childhood recordings. In that context, “Dos Arbolitos” feels less like a track selection and more like a family photograph slipped carefully into a frame.

And vocally—this is important—Ronstadt sings these words without turning them into spectacle. She lets the metaphor do its work. She trusts the song’s humility. That restraint gives the lyric room to bloom: you start with two trees, and end somewhere far more personal, in the place where pride finally admits it wants tenderness, where independence quietly asks for shelter.

The loveliest thing about “Dos Arbolitos (Two Little Trees)” is that it doesn’t beg you to be impressed. It simply shows you something true: closeness can be ordinary, almost unnoticed—two trunks in the same earth, two crowns touching in the wind—until one day you realize you’ve been living your whole life searching for that kind of steady presence. And when Ronstadt sings it within Canciones de Mi Padre, the song becomes more than romance. It becomes a meditation on roots—on what we inherit, what we return to, and what we still dare to ask the sky for when the evening gets quiet.