A Wry Smile at Life’s Imperfections and the Quiet Art of Contentment

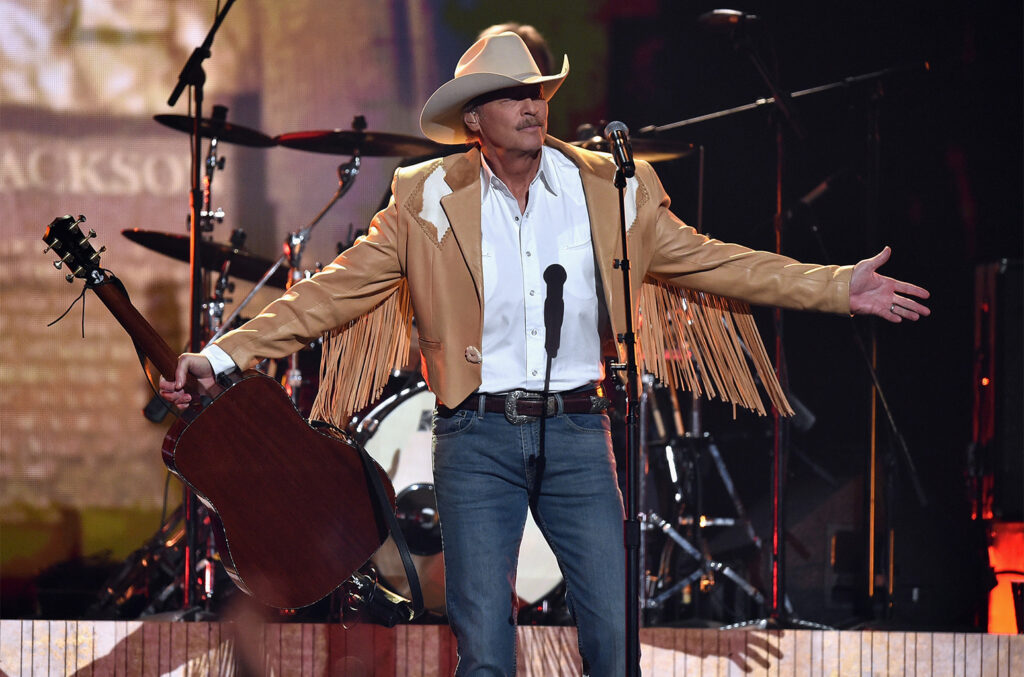

When Alan Jackson released “That’d Be Alright” in late 2001 as the final single from his Grammy-winning album Drive (2002), it rode the crest of one of his most creatively fertile periods. The song climbed into the Top 5 on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart, reaffirming Jackson’s uncanny ability to distill Southern wisdom into three effortless minutes of melody and charm. Coming off the emotional heft of his earlier hits—especially the deeply reflective “Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning)”—this track offered something lighter, even mischievous: a shrug at life’s complications, delivered with a knowing grin and an old guitar’s hum.

Beneath its genial exterior, “That’d Be Alright” is a masterclass in Jackson’s signature brand of everyman poetry. Co-written by Tia Sillers, Tim Nichols, and Mark D. Sanders—each a craftsman of country narrative precision—the song finds Jackson inhabiting a character who dreams small but dreams true. The desires he lists are neither grand nor unreachable; they’re rooted in the humor of daily striving. It’s a clever satire of modern ambition, a wink at our endless yearning for something easier, richer, or just a little more fun. Yet at its heart lies an undercurrent of peace with imperfection—a reminder that maybe we’re already closer to “alright” than we realize.

Musically, Jackson keeps the arrangement grounded in his neotraditional roots: crisp Telecaster twang, a shuffle rhythm that rolls like a well-worn pickup on a country road, and that warm baritone delivery—half smile, half sigh—that could make even life’s smallest disappointments sound like blessings. There’s an intimacy to his phrasing here, as if he’s leaning on the bar next to you, telling a joke that hides a truth you both recognize but rarely say aloud. The band’s interplay feels organic, almost offhanded, giving the track a breezy looseness that mirrors its lyrical spirit.

Yet what makes the song endure is not merely its wit or craftsmanship—it’s its philosophical weight disguised as simplicity. “That’d Be Alright” occupies the same emotional terrain as Jackson’s finest work: a deep understanding that contentment is not found in escaping life’s frustrations but in laughing with them. This is the quiet rebellion of country music at its best—a refusal to let cynicism win, even when the world offers plenty of reason to surrender to it.

In the grand mosaic of Alan Jackson’s career, “That’d Be Alright” stands as both a breather and a revelation: proof that wisdom sometimes wears a smile, that humor can be holy, and that even the smallest wish—spoken plain over a steel guitar—can echo with truth long after the laughter fades.