A Lament for Love Lost in Neon Glow and Sawdust Solitude

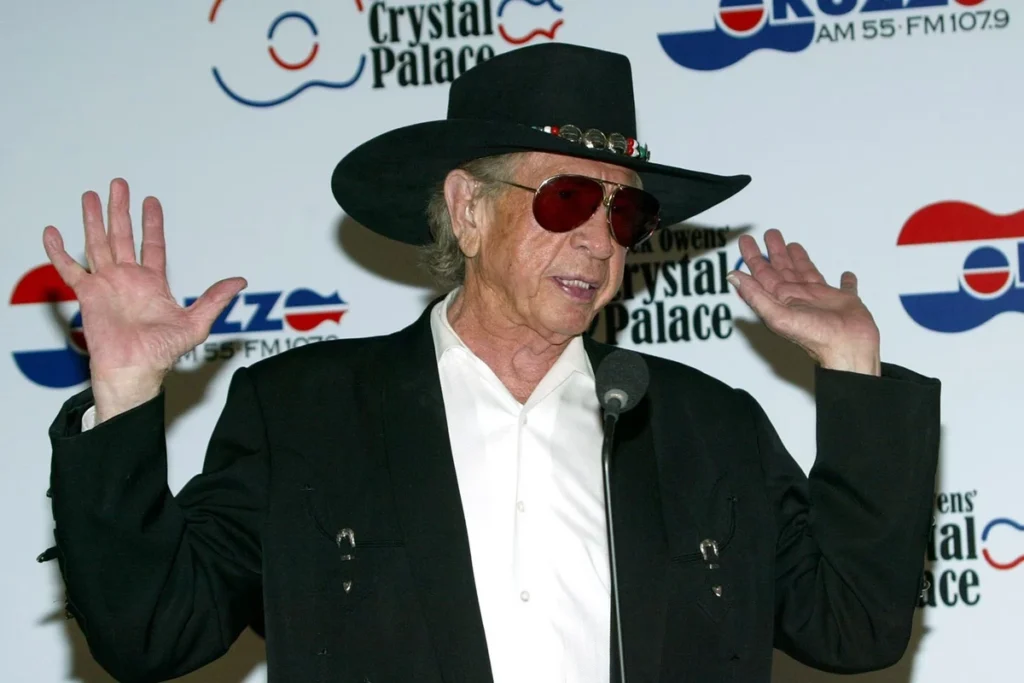

When Buck Owens released “Close Up The Honky Tonks”, it wasn’t presented as a headlining single, nor did it storm the charts in its own right upon first release. Instead, the track first emerged as the B-side to “My Heart Skips a Beat” in 1964—an era when Owens was helping to redefine the boundaries of country music with his signature Bakersfield Sound. Featured later on the compilation album Best of Buck Owens, Vol. 2, the song didn’t need commercial fanfare to carve its niche. It became a staple not because of radio rotations or chart accolades, but because of its raw emotional truth—an aching slice of heartbreak delivered with dust-covered sincerity.

To understand “Close Up The Honky Tonks,” one must first understand where Buck Owens stood in the cultural landscape of 1960s country music. While Nashville was polishing country into something smooth and orchestrated, Owens and his peers out West were doing the opposite—stripping it down to twangy Telecasters, punchy drumbeats, and an unfiltered emotional current that resonated with the working class. The Bakersfield Sound wasn’t just a musical movement; it was a rebuttal—a refusal to let heartache be drowned out by string sections and studio gloss.

And what deeper heartbreak than the betrayal and disillusionment painted in this song? “Close Up The Honky Tonks” is not merely about jealousy or sorrow—it’s about the desperation to shut down an entire world so one man can escape his anguish. Owens sings:

“She’s in some honky tonk tonight, I know / She’s dancing where the music’s loud and lights are low.”

It’s not just his lover he’s losing; it’s his grip on reality, his faith in loyalty, perhaps even his place in a culture that once seemed safe. His solution? Not confrontation. Not redemption. But obliteration: shuttering every honky tonk where she might be found, silencing the jukeboxes, turning off the lights, ending the dance before it begins.

In doing so, he articulates a uniquely masculine grief—the kind that doesn’t cry openly but broods in silence, fueled by whiskey and worn leather barstools. It’s worth noting that Owens’ delivery is restrained, almost stoic; his voice doesn’t break, but something inside him clearly has.

Musically, the song leans into minor-key melancholy without sacrificing that driving Bakersfield rhythm. There’s tension between motion and stasis—the beat moves forward while the narrator remains emotionally paralyzed. This duality is key to the song’s enduring appeal: it captures a moment of pain frozen in time, yet wrapped in instrumentation that keeps circling back like memory itself.

Though others would go on to cover this song—Dwight Yoakam, k.d. lang, and notably The Flying Burrito Brothers, whose 1969 version infused it with cosmic Americana sorrow—it is Owens’ original recording that holds closest to the bone. It may not have been a commercial juggernaut, but like so many great country songs of its era, its power lies in how deeply it resonates across generations.

“Close Up The Honky Tonks” remains a twilight confession for anyone who has loved too hard and lost too much—its legacy not written in gold records but etched into dim-lit corners of countless hearts where jukeboxes still glow and ghosts still dance.