A cheerful melody masking a gathering storm, “Bad Moon Rising” is Creedence Clearwater Revival smiling through prophecy—proof that the darkest warnings are sometimes delivered with the brightest sound.

When Creedence Clearwater Revival released “Bad Moon Rising” in April 1969, it sounded at first like a carefree, radio-friendly singalong—bright acoustic strums, quick tempo, and John Fogerty’s unmistakable, urgent voice. But beneath that sunny surface lay one of the most ominous songs of its era. Issued as a single backed with “Lodi,” the record climbed to #2 on the Billboard Hot 100, held off the top spot only by the cultural juggernaut “Love Theme from Romeo and Juliet.” In the UK, the song reached #1, confirming its global impact. It later appeared on CCR’s third studio album, Green River, released in August 1969, which peaked at #1 on the Billboard 200 and solidified the band’s status as America’s most reliable hitmakers of the moment.

The song was written by John Fogerty, who has often explained that “Bad Moon Rising” was inspired not by astrology or superstition, but by apocalyptic imagery—specifically the sense that disaster was approaching on multiple fronts. The late 1960s were saturated with unease: the Vietnam War escalating, political assassinations still fresh, social unrest simmering everywhere. Fogerty later said the song was about the apocalypse, about inevitable trouble coming whether people were ready or not. The “bad moon” was a symbol—a warning sign hanging silently in the sky.

What makes the song extraordinary is its emotional contradiction. Most protest or warning songs of the time wore their seriousness openly. “Bad Moon Rising” does the opposite. It dances while it warns. Its melody is rooted in classic American country and rockabilly traditions—fast, catchy, deceptively joyful. That contrast is not accidental. Fogerty understood something profound: people often absorb uncomfortable truths more easily when they arrive wrapped in familiarity and pleasure. The song slips its message past your defenses, and only later do you realize what it’s been telling you all along.

Lyrically, the warnings are unmistakable. “I see trouble on the way / I see earthquakes and lightnin’.” These are not personal heartbreak metaphors; they are collective omens. Floods, storms, ruined crops—Fogerty’s imagery feels biblical, echoing the language of old folk songs and American gospel, where natural disaster often stands in for moral or societal collapse. Yet he never points a finger at a single villain. The danger is systemic, atmospheric, unavoidable. It’s coming whether anyone wants to hear about it or not.

One of the song’s most famous cultural footnotes is also one of its most revealing. For decades, listeners misheard the line “There’s a bad moon on the rise” as “There’s a bathroom on the right.” Fogerty himself has laughed about this and even sang the misheard lyric in concert. But the joke carries irony: a song warning of catastrophe became so embedded in everyday life that people sang along without fully hearing the message. In a strange way, that mishearing perfectly mirrors the song’s theme—danger approaching while people hum along, distracted.

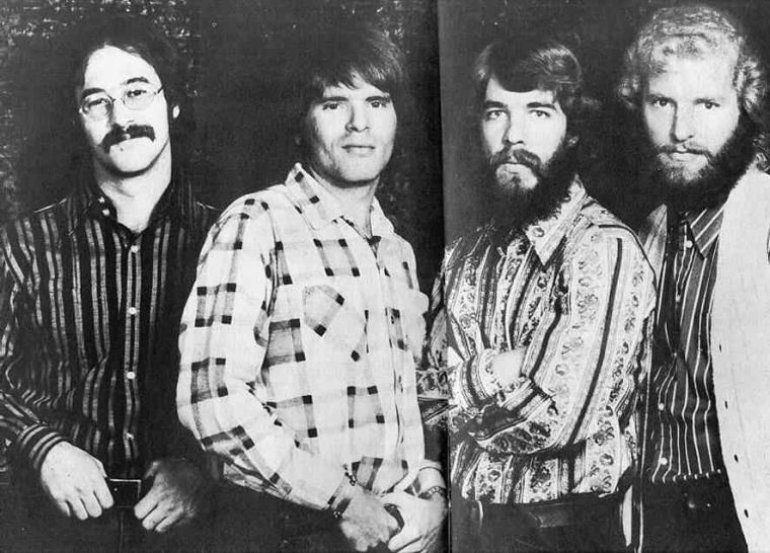

Musically, Creedence Clearwater Revival are at their most efficient here. The band never wasted a second. “Bad Moon Rising” runs just over two minutes, yet it feels complete, urgent, and timeless. Doug Clifford’s drumming drives the song forward without flourish, Stu Cook’s bass keeps it grounded, and Fogerty’s rhythm guitar locks everything into motion. Nothing is indulgent. Everything serves the message.

Within Green River, the song plays a crucial role. The album balances nostalgia (“Green River,” “Wrote a Song for Everyone”) with disillusionment (“Commotion,” “Bad Moon Rising”). Together, they paint a portrait of America caught between memory and reality—longing for simpler times while sensing that something is deeply wrong. “Bad Moon Rising” is the album’s warning bell, ringing loudly but cheerfully, as if hoping the smile might soften the shock.

Over the decades, the song has never lost relevance. It resurfaces whenever the world feels unstable—used in films, television, and public moments to signal approaching trouble. Yet it’s often misunderstood or casually repurposed, stripped of its meaning. That, too, feels appropriate. Fogerty didn’t write a song that demands to be studied; he wrote one that insists on being remembered, even if only subconsciously.

The enduring meaning of “Bad Moon Rising” lies in its realism. It doesn’t offer solutions. It doesn’t promise rescue. It simply says: pay attention. Trouble doesn’t always announce itself with sirens. Sometimes it arrives smiling, humming a tune you already know.

And that is why the song still resonates so deeply. Because long after the charts fade, after the era’s headlines blur, that bright little melody still carries its quiet warning—rolling forward through time, reminding us that history has a rhythm, and storms often come with plenty of notice… if we’re willing to listen.

In the end, “Bad Moon Rising” isn’t pessimistic.

It’s honest.

And honesty, especially when sung with a smile, can be the most unsettling sound of all.