“Cotton Fields” is a postcard from the American soil—childhood memory and hard labor braided together, where a simple melody carries the weight of history.

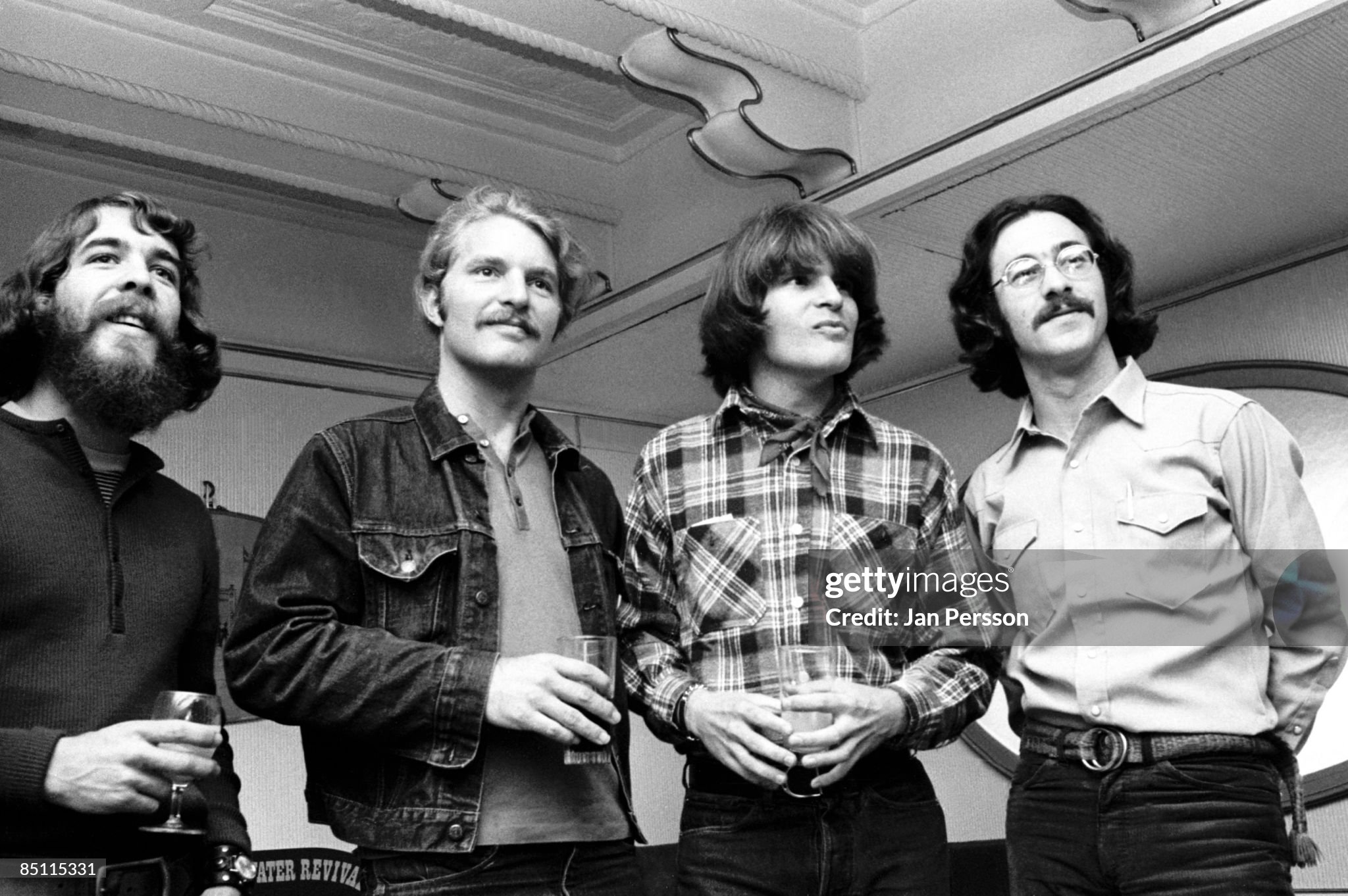

There’s a particular kind of magic when Creedence Clearwater Revival step into an old folk song and make it feel both immediate and eternal. With “Cotton Fields (The Cotton Song)”, they don’t treat the past like a museum—sealed behind glass and labels. They treat it like a living road you can still walk on, barefoot if you choose, feeling every stone and splinter. Their recording sits as the third track on Willy and the Poor Boys, released on October 29, 1969, at the exact moment when CCR were moving at an astonishing creative pace, turning American roots music into something lean, modern, and fiercely memorable.

The song itself begins long before Creedence touched it. “Cotton Fields” was written by Huddie Ledbetter—Lead Belly, one of the crucial voices in American folk and blues, a songwriter who knew how to turn lived experience into a melody that could travel far beyond its birthplace. The lyric feels deceptively gentle at first: a child rocked in a cradle, a mother’s steady comfort, the world still small enough to fit in a lullaby. But the backdrop is unmistakable: the cotton fields—work, endurance, and the complicated inheritance of the American South.

CCR’s version holds onto that simplicity, yet it also sharpens it. One of the most telling details is geographic—those famous lines placing the fields “down in Louisiana” near Texarkana. Lead Belly’s original wording places the fields “ten miles” from Texarkana, while later versions—including Creedence’s—shift it to “about a mile.” It’s a tiny change, almost casual, but it does something emotionally: it brings the scene closer, as if the memory has tightened its grip, as if the past is not far off at all.

Musically, Creedence keep it brisk and earthy—no frills, no ornament, no attempt to “pretty it up.” The performance has that familiar CCR propulsion: a rhythm that moves like a working engine, guitars that bite without showing off, and a vocal that sounds plainspoken but deeply felt. John Fogerty doesn’t sing it like a narrator reading history; he sings it like someone who can smell the heat rising off the ground. In Creedence’s hands, nostalgia is never soft-focus. It’s tactile. It has weather.

Because “Cotton Fields” lived on an album packed with more obvious radio staples, its early life was less about a big U.S. singles moment and more about becoming part of the band’s larger mythology—CCR as the great American translators, taking folk, blues, country, and early rock ’n’ roll and turning them into three-minute truths. Still, the song found striking success in other ways and other places: CCR’s recording is noted as having hit No. 1 in Mexico in 1970—a reminder that music doesn’t always bloom where industry expectations predict.

Then, years later, the song returned with a very particular kind of second life. In October 1981, Fantasy Records released the compilation Creedence Country, explicitly aimed at the country market. From that compilation, “Cotton Fields” was issued as a single backed with “Lodi” in November 1981—and this time it carried a chart story: it reached No. 50 on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles in early 1982. That chart position is quietly poetic. A song about fields, labor, roots, and the old ways eventually found itself recognized on a chart built around American roots traditions—almost like the music had come home by taking the long way around.

What does “Cotton Fields” mean when Creedence sing it? It means that tenderness and hardship can exist in the same breath. It means that childhood can be remembered with warmth even when it took place in a world shaped by work and worry. It means that “home” is not always an easy word—it can be comfort and burden at once. And perhaps most of all, it means that a simple song, sung plainly, can carry generations inside it.

That’s why “Cotton Fields” endures in the CCR catalog. Not because it tries to be grand, but because it refuses to lie. It hums with memory, and it walks forward with purpose—one steady step at a time, like someone returning from the fields at sundown, tired but still singing.