“Feelin’ Blue” is CCR’s slow, midnight confession—less a song you hear than a mood you wear, like a coat that still smells faintly of rain and old roads.

If Creedence Clearwater Revival often feels like motion—rivers rolling, trains passing, bad moons rising—then “Feelin’ Blue” is what happens when the moving finally stops and the silence gets a vote. It’s a deep album cut that doesn’t chase applause. Instead it lingers in the half-light, letting the band’s famous economy stretch out into something more patient and bruised. You don’t put it on for excitement. You put it on when you need music to tell the truth without decorating it.

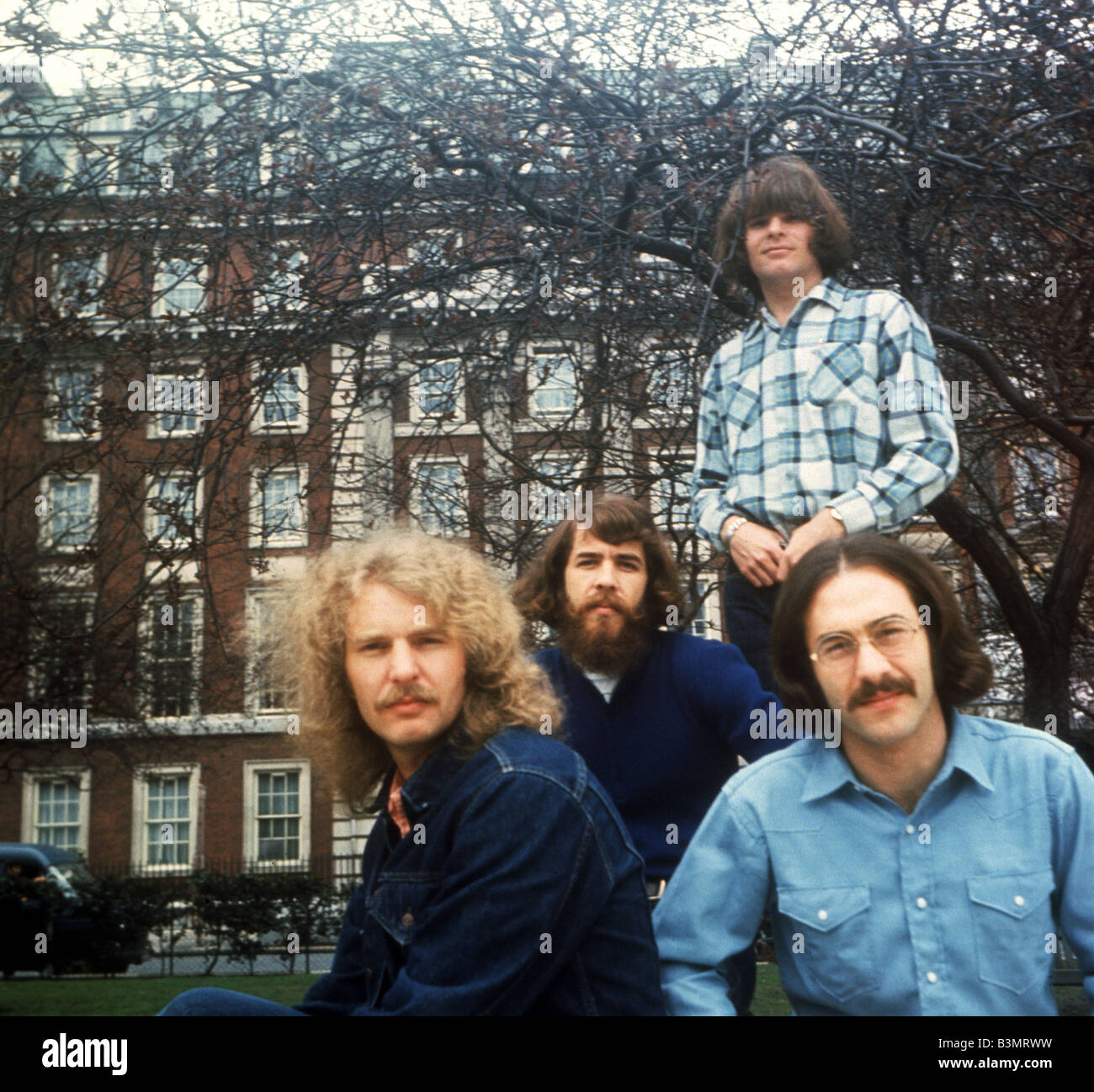

Here are the hard facts first, clean and accurate. “Feelin’ Blue” is a John Fogerty composition and appears on CCR’s fourth studio album Willy and the Poor Boys, released by Fantasy Records on October 29, 1969. The album was recorded at Wally Heider Studios (San Francisco) and produced by John Fogerty. On the original track sequence, “Feelin’ Blue” closes Side One as Track 5, running about 5:05–5:06 depending on pressing/mastering. It was not released as a single, so it has no individual chart placing—its “ranking” story belongs to the album that carries it.

And that album mattered. Willy and the Poor Boys—packed with era-defining songs like “Down on the Corner” and “Fortunate Son”—peaked at No. 3 on the Billboard 200, part of CCR’s astonishing run of releasing three studio albums in 1969. Within that context, “Feelin’ Blue” is almost a secret room inside a house everyone already knew: the reflective space tucked behind the radio headlines.

What makes the track especially memorable is how it’s framed. On the album, an instrumental called “Poorboy Shuffle” leads directly into “Feelin’ Blue”—a handoff that feels like walking from street-corner bustle into a quieter bar at the edge of town. That transition is not just sequencing; it’s storytelling. CCR briefly plays at being the good-time jug band suggested by the album’s concept, and then—without warning—lets the curtain fall to reveal something more private.

Musically, “Feelin’ Blue” stretches CCR’s usual compact punch into a longer, looser burn. The groove stays grounded, but the atmosphere widens: a blues-based crawl with room for the band to breathe. It’s still unmistakably CCR—no psychedelic fog, no ornate studio tricks—yet the pacing feels different from their hit machinery. The band lets the sadness take its time. That choice is the whole point. Some emotions don’t fit into 2:30.

The meaning of “Feelin’ Blue” isn’t complicated in the lyrical sense—and that simplicity is why it cuts. Fogerty’s writing here is direct, almost plainspoken, as if the singer is too tired to perform his grief. This is not melodrama. It’s that quieter, older kind of sorrow: the kind you carry while doing ordinary things, the kind that doesn’t demand witness yet still wants to be acknowledged. In CCR’s hands, “blue” isn’t a color for poetry; it’s a condition.

There’s also an important historical note behind the song’s shape. One often-cited account—drawing on a Fogerty interview history—says he had the idea as early as 1967, struggled to complete it for earlier sessions, and only later found the right way to assemble it. Whether you treat that as strict chronology or as the messy truth of songwriting memory, it matches what you hear: “Feelin’ Blue” sounds worked into place, like a thought revisited until it finally said what it needed to say.

What I love most about “Feelin’ Blue” is how it deepens the emotional architecture of Willy and the Poor Boys. This is the album that gave the world a sing-along street-corner anthem and one of rock’s great class-and-war indictments. Yet it also makes room for a long, weary blues meditation right at the end of Side One—as if CCR insisted that even in a year of speed, success, and loud cultural arguments, the ordinary ache of a single person still deserved five full minutes.

That’s why the song endures. “Feelin’ Blue” doesn’t try to be legendary. It simply tells the truth with a steady pulse and an unguarded voice. And sometimes, that’s the most “classic” thing a record can do: not lift you above your feelings, but sit beside them until the night passes.