50 years on from a catastrophic David Cassidy concert, Dave Thompson recalls that awful night.

American pop idol David Cassidy arrived through the back door of Radio Luxembourg while his fans waited in the rain at the front of the building. But not to disappoint his fans, David made two appearances on the balcony overlooking Hertford Street where the traffic had been stopped by the massed fans, May 23, 1974. Photo by Peter Stone/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

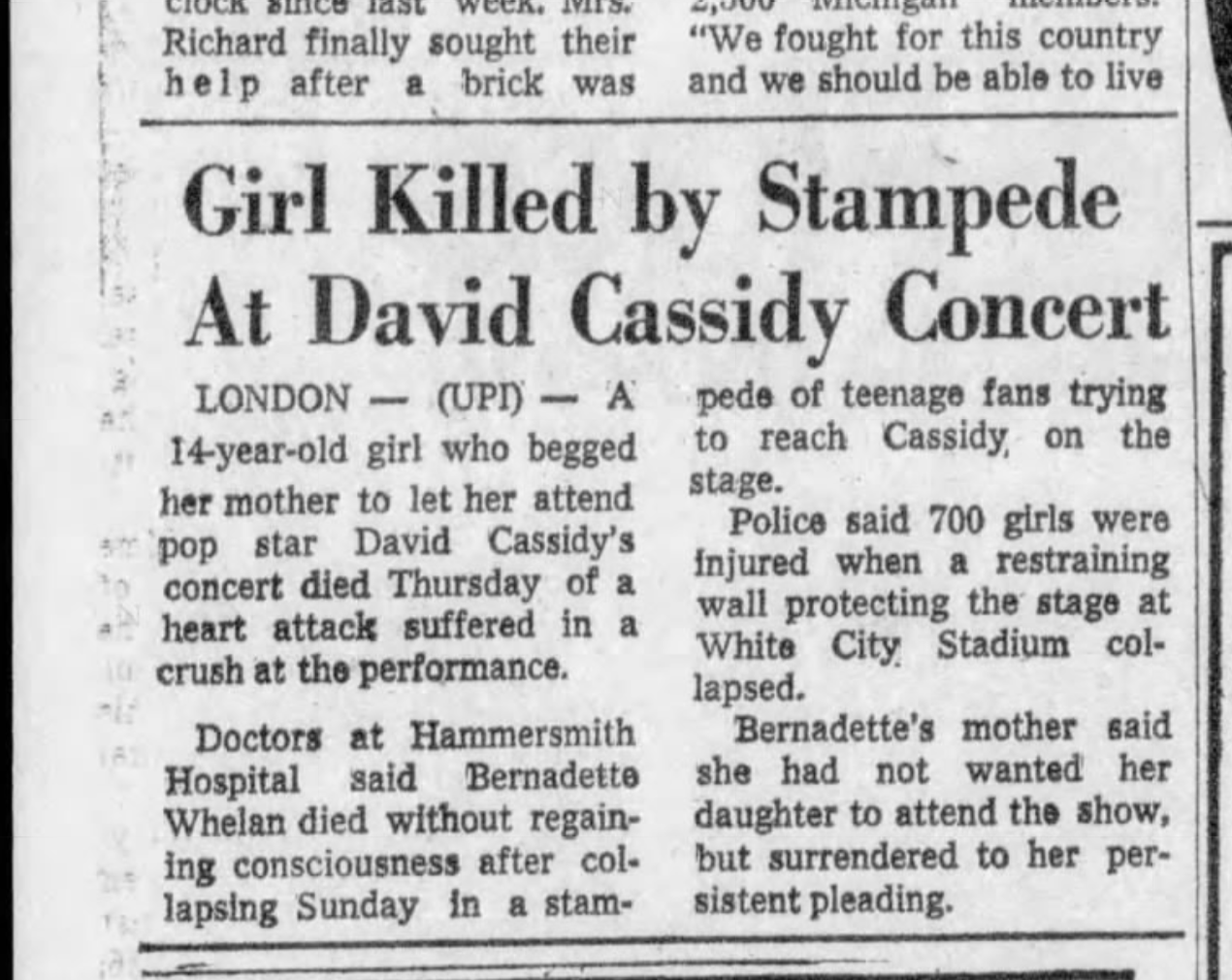

Bernadette Whelan died on May 30, 1974, four days after her comatose body was placed on life support, the 14-year-old schoolgirl passed away in west London’s Hammersmith Hospital. Official cause of death: traumatic asphyxiation. Actual cause of death, in the coroner’s own words, “a victim of contrived hysteria.”

The hysteria that engulfed a David Cassidy concert.

Cassidy was huge in 1974, as huge as he’d been in 1971, 1972, 1973. But he was tired, too. For four years, he had lived life within that uniquely demented goldfish bowl that only a true teenybop idol could inhabit… today, even the vaguest, most talent-free nonentity can be raised to tabloid mega-godhood by a celebrity-crazed media. Back then, however, you really needed to have something to set the papers’ pulses racing, and Cassidy had it in abundance.

A television idol before he was a pop icon, the male lead in The Partridge Family and one of just two “band members” whose voice would appear on the group’s hit records,(the other was his TV mom and real-life stepmom Shirley Jones), Cassidy’s U.K. success was beyond vast. It was Brobdingnagian…

Whereas his American albums tended to run out of steam long before they sniffed the Top 10, British fans sent Cherish and Rock Me Baby soaring to No. 2; and Dreams Are Nuthin’ More Than Wishes to the top.

A group of girl fans hold a banner for American pop idol David Cassidy when he visited the London Weekend Television headquarters at Waterloo, London, on May 25, 1974.

Photo by PA Images via Getty Images

Photo by PA Images via Getty Images

While his biggest U.S. hit, “Cherish,” made No. 9 on the Billboard chart, in Britain he was rarely off the listings, seldom far from the Top 5. And when Top of the Pops, a national television institution, celebrated its 500th edition in October 1973, Cassidy was flown to London by the BBC, simply so they could include film of him on the tarmac.

Bernadette adored him. She had followed him for what, in teenage terms, was “forever.” She was 11 when The Partridge Family commenced airing in the U.K. in September 1971 (a full year after its American counterpart), and had been glued to the screen ever since.

Later, when the newspapers descended upon her home in Stockwell Park, south London, a nearly life-sized poster of a gorgeous, glowering Cassidy dominated the wall above her headboard, and his music was scattered over her neatly-made bed. Of course she hadn’t left the room like that herself; the discs were probably posed there by the photographers. But they made their point. There was no doubt where Bernadette’s heart lay. Not even her mother Bridget’s staunch refusal to allow the girl to attend the show could withstand her constant pleading. Finally, mom relented.

Which only makes the circumstances of Bernadette’s death all the more tragic.

In early 1974, Cassidy announced that he was quitting music.

There would be one final burst of live shows, in London, Glasgow and Manchester, and that would be the end. “I feel burnt up inside,” he told Britain’s Daily Mail. “I’m 24, a big star … in a position that millions dream of, but the truth is I just can’t enjoy it.”

Years later, looking back for the same newspaper, he elaborated further. “I was definitely the most isolated I’ve ever been. I’d be working seven days a week for most of the year and it never let up. When I got home, I isolated myself, just so I could rest. And because I couldn’t go to the bank or shop like normal people, I had a housekeeper who took care of everything. I hadn’t lived; I’d devoted myself to the business of David Cassidy, rather than the person.”

Now it was time to reverse the process, to turn his back on everything he had achieved over the past four years, and say goodbye to his most loyal fans. Tickets for those last three dates sold out in record time, even in those days when people (probably the parents on this occasion — the audience itself would have been at school) had to line up for hours at an overworked ticket office.

The London show, while not the last of the tour, was the grandest. White City, in Shepherd Bush, west London, was a 35,000-capacity sports arena built in 1908 to house the London Olympics.

It was a comparative stranger to live concerts. Only once before had it been plunged in to such waters, as the none-too-successful host of the 1973 Great Western Express Festival, an event featuring Canned Heat, Barclay James Harvest, Lindisfarne and the Edgar Winter Group, but best remembered for Ray Davies’s emotional “retirement’ speech at the end of The Kinks’ set.

No way could that event be compared to this….

The siege began early. London was still waking up on the morning of May 26, a Sunday, and already the first figures were gathering around the stadium. The doors would not open for hours to come, but merchandise sellers were already in place, hawking scarves and buttons, T-shirts and unofficial programs.

Photo by Allan Olley/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

The first ticket-holders were milling around, keeping a watchful eye for every conceivable place of entry in case Cassidy should arrive at the venue early. The ticketless were out in force, too, and with them the inevitable army of hyena-breath ticket touts, themselves constantly shuffling from spot to spot, aware that their trade was wholly illegal, but knowing that few cops would have the time to do anything. Not with a crowd this size to watch.

That was, in fact, the police’s sole intention. To watch the crowd. They would step in if they saw tempers flare, of course; keep order if kids grew too boisterous, nab any pickpockets who thought they’d try their luck. And, by their very presence, reassure any parents dropping their offspring off for the show, to be consumed by the seething horde.

Venue security itself was left in the hands of the hired hands, the 200 or so bouncers brought in from an outside agency to guard the stage throughout the show, and the doors for the rest of the time. Interviewed for a television report the previous year, when Cassidy played Wembley Arena, one security guy described teenaged girls armed with crowbars, attempting to force open the doors around the hotel where he was staying. Would they try the same trick tonight?

Another claimed fans were turning up with pockets full of sleeping pills, which they would drop into the bouncers’s cups of tea — he did not, sadly, explain, how the fans got that close to the drinks in the first place. And then there were the girls with wire cutters secreted about their persons, to snip their way through the fences that separated crowd from performer. “They get up to the most fantastic tricks,” one of the strongmen concluded.

Such mischief notwithstanding, nobody was expecting trouble at White City.

One estimate placed the average age of the audience around the early-mid teens, and predominantly female too.

Besides, what could happen at a pop concert? This was David Cassidy the kids were going to see, not some spaced out hippy band whose entire audience was high on illegal drugs, or some twisted metal act who would convert the crowd to Satanism. And this was London, not Woodstock; this was Shepherds Bush, not Altamont.

If anyone was at risk, it was Cassidy himself. Back to the bouncers… “If these kids got near him, they’d kill him.”

Bernadette, like so many others, arrived at the venue long before the doors opened; it was later reported she’d probably been on her fashionably platform-booted feet for 12 hours, both outside and inside the stadium. Finally, however, showtime dawned and the crowd flowed as one into stadium, its components separating only as they spread out in search of the best vantage point.

Photo by Peter Stone/Mirrorpix/Getty Images

The support band, Cassidy’s Bell Records labelmates Showaddywaddy, took the stage, and left it again at the end of their set, uncertain whether anyone in the place — themselves included — had heard a single note they played. From the stage, the audience did not even look human, just a vast surrealist montage of posters, scarves, and waving arms, soundtracked by squeals of love, dedication and undying adoration, and above and behind and around all that, an every-sense-pervading web of wall-to-wall screaming.

The 200 security staff took their positions in front of the stage and at strategic spots around it, the loyal battalion protecting the king on some muddy medieval battlefield.. All were experienced, doughty veterans of so many past confrontations… Beatle-Osmond-T.Rexstacy-mania; you name it, they’d fought there… But they had never faced anything like this as 35,000 hysterical teens made it clear that they would stop at nothing to reach the object of their desire.

Jet planes were quieter than the crowd. Backstage, the recording engineers could barely hear themselves think as they tried to find their levels — Bell Records was recording the show, and a souvenir album, Cassidy Live, would be along before the seats were even dry. But you try checking levels when the only sound is an undulating howl; when the greatest microphones money can buy are quailing before that ecstatic keening. A couple of years later, Lou Reed released Metal Machine Music, four sides of painstakingly manipulated feedback. He could have just taped tonight’s audience.

Cassidy hit the stage, and the teenaged lung power hit cacophonic proportions, frenzied, ear-piercing, glass-shattering, a wail that confined the most vibrant amplified music to a mere bit part in the unfolding audio drama. Even Cassidy, who’d seen (and heard) it all before looked stunned by the noise that enveloped him.

With sound came motion. The crowd was pushing, seething, every body in the place straining to get as close to the stage as possible, a mass of writhing, pushing, pressing bodies all with but one objective in mind. To see, perchance to touch, the idol.

Then, somebody tripped, or stumbled, or fell, and anything up to 1,000 fellow concert-goers fell with them.

And the tapes kept rolling.

It wasn’t the falling that hurt, of course. It was the crushing. It was the weight first of one, then of ten, then a hundred, and then a thousand (newspaper reports varied… some said it was as few… few!!!… as 650) bodies falling onto one another, a teenaged sea that was suddenly transformed into a human log jam.

Listen back to the tapes. The show was about 20 minutes in when it first became apparent that something had gone wrong; that sudden, awful moment when an unyielding barrage of impassioned screaming became a horrified explosion of terror.

From the stage, unaware of what precisely had happened, but knowing that something was wrong, Cassidy struggled, ineffectively, to restore order. While security and the St John’s Ambulance volunteers tried to push through the melee, he halted the music and shouted to the crowd. “Get back, get back. They’re going to stop the show, they’re going to pull the plug on me. Cool it!”

But like Mick Jagger at Altamont five years earlier, his words had no effect. Cassidy left the stage and the PA kicked into whatever lightweight pop was to hand in a futile attempt to calm the crowd. And now the tape becomes surreal. To the jaunty soundtrack of “The Wombling Song,” the debut hit by children’s television’s favorite litter-collecting rodents, hundreds upon hundreds of crushed, bleeding and battered fans were calling, pleading, screaming for help. One of the St John’s men later compared the scene to the Blitz.

Slowly, those people who could picked themselves up. In fact, the vast majority, though they’d be registered as injured, would make it home unaided that night. Thirty, however, were rushed to local hospitals, and one, Bernadette, had stopped breathing altogether. Frantic and dedicated, emergency workers were able to restart her heart, but the girl was still unconscious as she was stretchered into one of the waiting ambulances.

She never regained consciousness.

Incredibly, the concert went on. The wounded were removed, the audience calmed, and Cassidy took the stage again. He had no idea of the magnitude of what was still being described as “an incident”; no notion, until the show was over, that so many of his fans had been harmed.

When he did find out, his first instinct was to cancel the next concert, in Manchester two days later. Calmer (or, perhaps, more financially prudent) heads prevailed upon him to reconsider, and the gig did ultimately go ahead. But an event already muted by shocked newspaper headlines was further diminished when it became clear how many of the 20,000 ticket-holders were staying away. The venue was less than half full as anxious parents, horrified by the previous morning’s newspaper headlines, returned their children’s tickets. And still half a dozen fans were hospitalized.

Two days later, Bernadette died.

The blame game started long before that, of course, and it would become even more circus-like afterwards. From promoter Mel Bush’s office came the assurance that the majority of supposedly injured fans were faking it; that they assumed the stretcher-bearers would take them backstage where they might catch a glimpse of their hero, and recovered the moment they realized they were going in the opposite way.

Crueller still, it was suggested that Bernadette was suffering from a congenital heart defect and could have died anywhere. The fact that her heart decided to give out when she was lying on the floor, crushed beneath several hundred other girls, was pure coincidence.

Thankfully, the coroner put paid to that line of thought. Unequivocally, he told the inquest into her death that her cause of death was “traumatic asphyxiation” — she was literally crushed to the point where she could no longer breathe.

But his report went further, to investigate not only the cause of Bernadette’s death, but also the factors that led up to it. He noted the “trendy, high platform shoes” that a lot of the injured fans had been wearing, and suggested that many of those who fell were literally toppled off their heels. And taking a well-aimed pot shot at the entire teenybop phenomenon, he described Bernadette as a “victim of contrived hysteria.”

It is a condition that our media still revels in today.

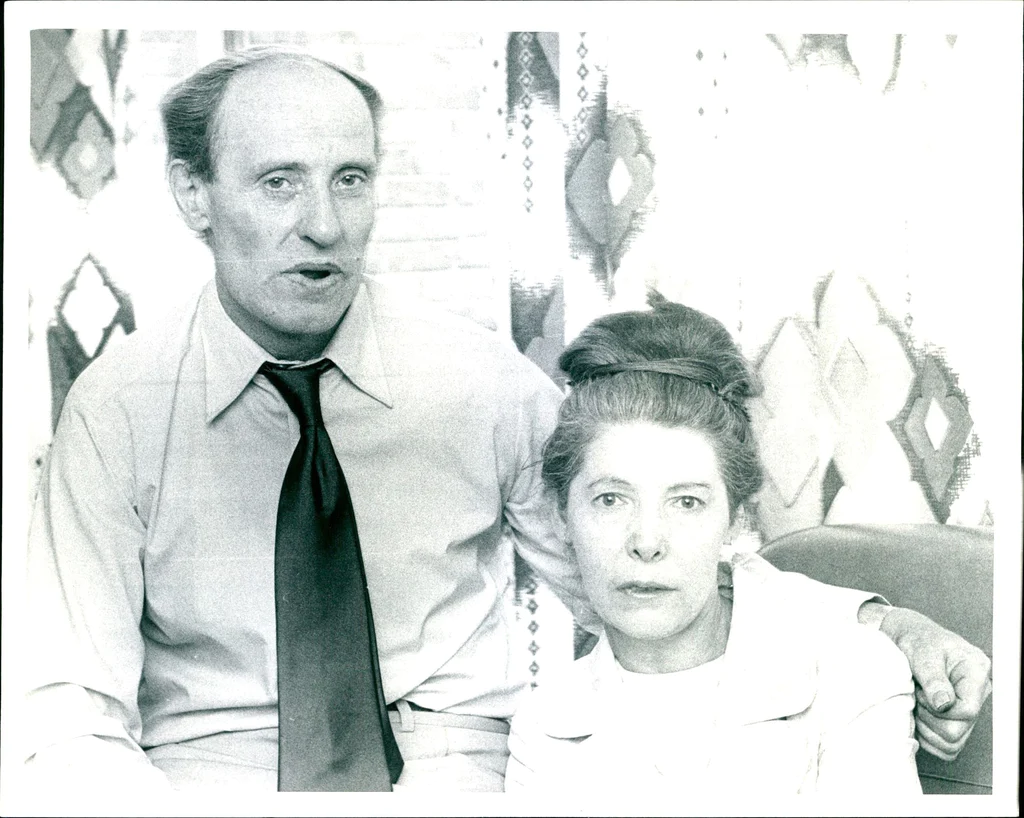

Bernadette’s parents, Peter and Bridget

For obvious reasons, Cassidy did not attend Bernadette’s funeral. He was in constant contact with her family, however, and he sent flowers, too. “We don’t blame David,” her parents Peter and Bridget told the media. “Bernadette would not have liked us to blame him.”

Years later, not long before his own death in 2017, Cassidy described Bernadette’s death, without question, as the worst thing that ever happened to him. It was 1985 before he finally returned to live performance and he admitted, every time he stepped out on stage, he remembered that night. He remembered Bernadette.

The buck continued to be passed. The company that provided the evening’s security rushed out a statement insisting that the disaster didn’t even fall under their purview. Their duty was nothing more, they said, than to “stop… children getting onto the stage, which was done successfully.” It was also pointed out that the law of the day insisted venues provide one bouncer per every 250 audience members. Add in the stadium’s own regular security, tonight there was one for every 100. So nobody could fault their dedication to duty.

The Greater London Council, the body responsible for licensing all public events, washed its hands clean with what still seems the frankly absurd insistence that they were unaware the country’s biggest teenaged idol was even playing a show that night. It was the promotor who was at fault, they said, for not telling them. Did absolutely nobody in that entire, massive, building have access to either a television or a newspaper, all of which had maintained a barrage of pre-concert coverage from the moment Cassidy’s arrival was first announced?

Back, then, to the Mel Bush Organization, whose tersely worded response was “to make it clear that in our opinion, and even with the benefit of hindsight, we took every precaution for the orderly running of the concert and the safety of those attending.” And again, that blanket assurance that “the vast majority of girls treated were treated on the spot for matters resultant from emotional stress and a very small number required hospital treatment.”

Oh, well that’s alright then.

However, it did acknowledge that “the age of the audience is a factor that in the future we should perhaps take more into account,” and here was a scapegoat that a lot of people could get behind. The youth and temperament of the audience. Never trust a teenybopper

According to Michael Alfandary, one of the promoters who had bid, unsuccessfully, for the right to stage the Cassidy shows, “open air venues are unsuitable for large numbers of young hysterical fans. I think an artist who makes a living out of hysterical devotion should play more shows at smaller halls, so the audience aren’t at risk.”

Bell Records head Dick Leahy continued in a similar vein, declaring that “the heart of the problem is the lack of suitable venues for big American acts” — although neither Wembley Stadium (100,000), Earls Court (18,000), Crystal Palace (15,000) nor the growing number of soccer stadia that were now hosting concerts (30- 40,000 plus) seemed to have any difficulty in providing a safe day out.

And amidst all of this handwringing and Pilate-ian hand-washing; out of the myriad mouths that spewed gas and garbage into the media back then, with their weasel words and butt-covering bull-cookies… the only person who actually said sorry, and meant it, was David Cassidy. Who was, in fact, the most blameless participant of them all.

So round and round the buckpassing passed. But time passed, too, and the horror slowly faded, new pop idols swiftly arose, fresh sensations devoured the headlines. And nothing whatsoever changed.

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents, who’d been campaigning for safer public events ever since 66 people died at a Glasgow soccer match in 1971, continued campaigning, and continued to be ignored until 1989 saw 96 people killed in a crush at another soccer match. That was what it took for the government to finally set about reforming an entire industry, not the death of one little girl at a pop concert. Although the timing of the disaster was interesting. The game itself, at the Hillsborough stadium in Sheffield, took place just two weeks shy of the 15th anniversary of Bernadette’s death.

David Cassidy had been back in at least a little limelight for four years by then. True to his word, he did retire in 1974, releasing a handful of seldom-noticed albums before making his slightly ballyhoo-ed live comeback in 1985 — around the same time, coincidentally, as the White City Stadium was demolished.

But he appeared before a very different concert audience to that he’d faced in 1974. Gone were the screamers, gone was the hysteria, and not gone, but grown, were the teenyboppers who once emptied their lungs in his honor. Now he was greeted by the women those girls had become, playing the hits they recalled from their crazy teenaged years, and smiling indulgently when one held out at a treasured souvenir of the old days. Some even brought their own children along, as if to show them that they, too, had once been young and silly.

Bernadette never had the chance to become one of those women, enjoying a night of gentle nostalgia within touching distance of her teenaged idol. Never had the opportunity to flick idly through her old scrapbooks, or wonder whether to buy David’s new album on CD, because how long was it since she played his old records?

She never had children, she never left school. She never really had a life, just a brief fourteen years, because one day she went to see her favorite pop star and she never came home again.

Fifty years have passed since then. She should be 64 years old. Instead she is forever 14. But she lives on in every gig we attend, in every record we play, in every music mag we look through, every pop-centric conversation we have, whether we’re tripping down memory lane or otherwise.

Not because of how she died, or where or why or whatever. Bernadette was neither a martyr nor a sacrifice, nor any of the other absurd tags that mythology likes to attach to its tragedies.

She lives on because she is the fan that we all once were, frozen in that moment in time when a person is poised between unquestioning musical devotion, and a more cynical outlook on the world around us…. the Not-Unknown Soldier of ’70s rock and pop.

And we, who remember our own days as a devoted onlooker, are the fans that she could and should have grown up to become.

Remember her, please.

(First published in part in Goldmine, May 31, 2016)