“Some Old Woman” is a song about how easily a life can be bruised by rumors—and how dignity sometimes survives only by telling the truth softly, again and again.

If you want the essentials first—because they set the emotional stage—David Cassidy’s “Some Old Woman (There Is A Woman)” appears as track 10 on his 1973 album Dreams Are Nuthin’ More Than Wishes, running 2:18, and credited to Shel Silverstein and Bob Gibson. The album itself was released in October 1973 on Bell Records, produced by Rick Jarrard, and it achieved a quietly astonishing feat: it reached No. 1 on the UK Albums Chart (dated 15 December 1973). In fact, its rise had the feel of a winter tide coming in—moving from a No. 7 appearance in the UK top ten (early December) to the summit two weeks later.

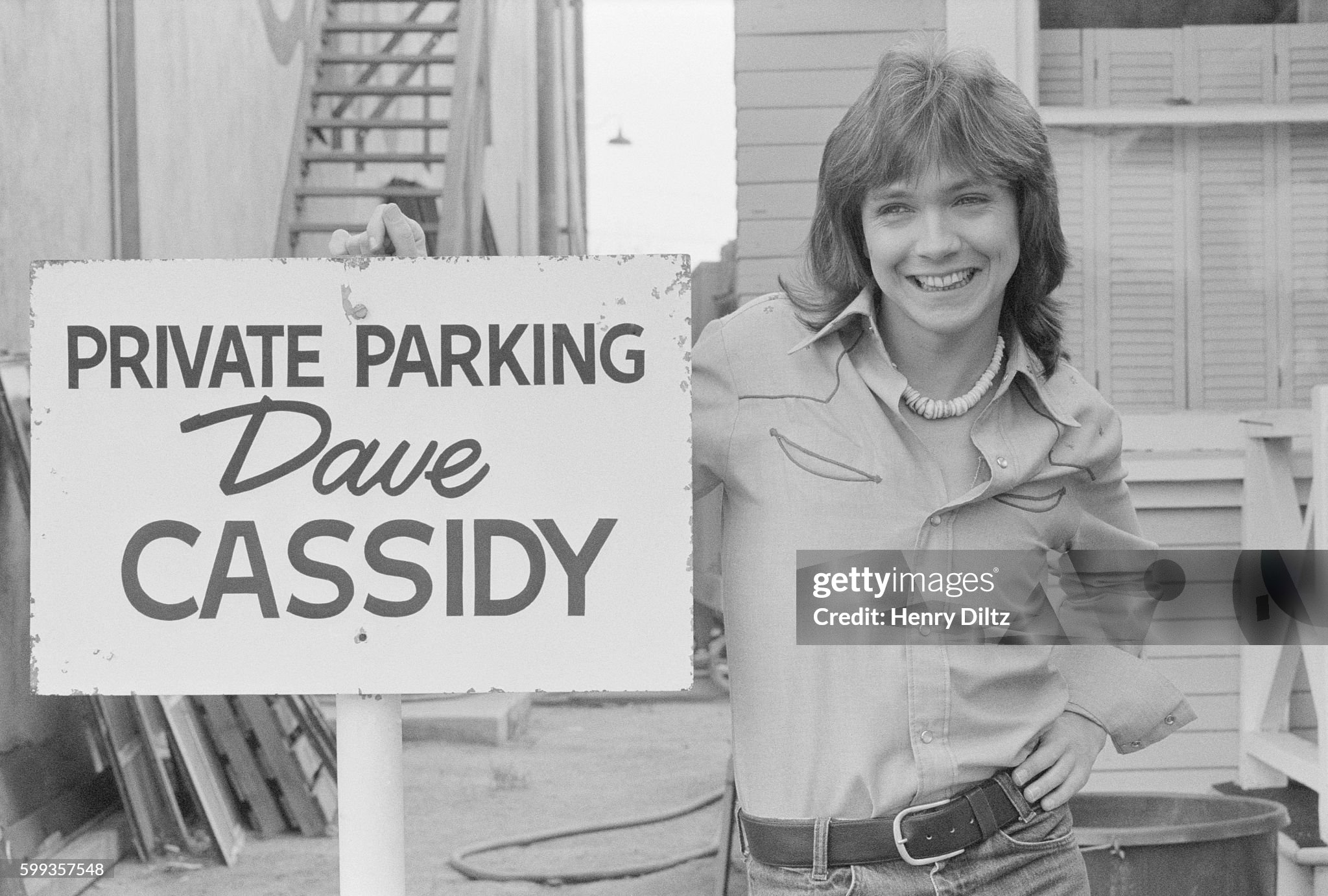

That success didn’t happen in a vacuum. Only weeks earlier, Cassidy had already been at the center of Britain’s radio heartbeat with the double A-side “Daydreamer / The Puppy Song,” which hit No. 1 with a first chart date of 13 October 1973. So when “Some Old Woman” turns up deep on side two, it feels almost intentionally private: not the single designed to charm a nation, but the album cut meant to reveal what the posters and headlines never could.

And what it reveals is unexpectedly dark—at least by the standards of the Cassidy mythology.

The song’s roots stretch back to the American folk world. Bob Gibson recorded “Some Old Woman (There Is a Woman)” on his album Where I’m Bound, and his family archive even preserves a period Billboard note (dated Dec. 21, 1963) praising the track among the set’s “first-rate” songs. On the Gibson legacy site, the composition is explicitly credited as “words and music” by Bob Gibson and Shel Silverstein—a pairing that explains the song’s bite: Gibson’s plainspoken folk directness meeting Silverstein’s gift for seeing the cruel joke inside everyday life.

So what is the “story” inside the song?

It’s the oldest kind of modern tragedy: someone in town is “telling lies,” and the damage doesn’t require violence or scandal—only repetition. In Cassidy’s orbit, where fame itself could act like a magnifying glass, that theme lands with extra weight. You can hear him stepping away from the bright, choreographed version of himself and into a scene lit by streetlamps: a man with a reputation he can’t fully control, trying to out-sing the whisper campaign. The title even sounds like something overheard—half accusation, half weary fact—like a sentence you never wanted to learn.

What makes David Cassidy’s version matter is how he reframes the folk original. His recording doesn’t feel like a coffeehouse cautionary tale; it feels like a late-night confession polished just enough for a studio microphone. The performance has that 1973 Bell-era sheen—carefully arranged, emotionally legible—yet the emotional center stays rough. There’s no swagger here, no wink to the audience. Instead, he leans into a particular kind of heartbreak: not being misunderstood by a lover, but misrepresented by the world.

That, ultimately, is the meaning of “Some Old Woman.” It isn’t simply about one woman, or one town, or one rumor. It’s about how fragile a name can be—how a person can do everything “right” and still be narrated by someone else. And it’s also about resistance: the refusal to let gossip become the final version of your story.

It helps to remember that Dreams Are Nuthin’ More Than Wishes was packaged with an unusually intimate touch—reports note its fold-out cover and handwritten notes from Cassidy explaining his song choices, as if he wanted listeners to meet him in the margins, not just in the chorus. In that light, choosing “Some Old Woman” makes a kind of emotional sense. When you’ve lived under constant attention, the sweetest songs can start to feel like costumes. Sometimes the truest thing you can do is sing something thorny—something that admits the world can be unfair, and that your heart has learned to bruise in silence.

And maybe that’s why the track still lingers for those who stumble upon it now. The hits may open the door, but “Some Old Woman” is where you hear the room behind the door: quieter, more complicated, more human—where the glamour fades, and the voice remains.