“Rockin’ All Over the World” is a simple rock chant that turns into a kind of passport—a reminder that joy can travel farther than trouble, and that a good groove can make strangers feel like neighbors.

In August 1975, John Fogerty released “Rockin’ All Over the World” as a single—backed with “The Wall”—and in one bright, compact burst (barely three minutes) he made an old promise feel new again: get your shoes on, come out tonight, let the music do the heavy lifting. The single’s story on the Billboard Hot 100 is the kind of steady climb rock radio used to reward: it debuted at No. 71 (week ending September 6, 1975) and eventually reached a peak of No. 27. Not a chart-topper—something better, in its own way: a record that earned its place by being played, lived with, and trusted.

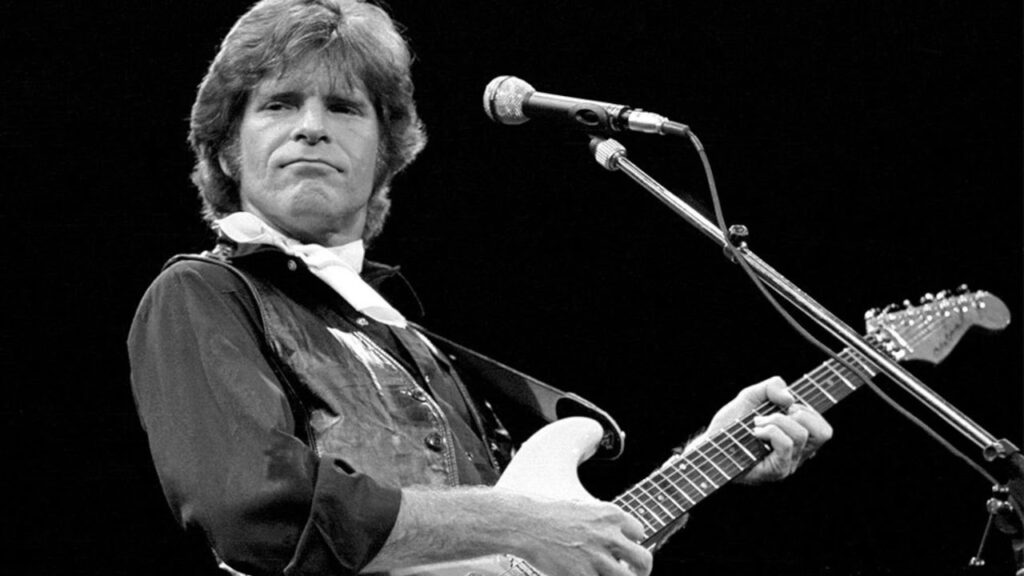

The song opens Fogerty’s 1975 self-titled album John Fogerty—released in September 1975—a record he later affectionately nicknamed “Old Shep,” after the dog pictured with him on the cover. That detail matters because it quietly sets the mood: this wasn’t a man chasing fashion. This was a man trying to feel grounded again—back on the porch of his own instincts, where rock ’n’ roll is made from plain materials: a tight rhythm, a bright guitar, and a chorus that repeats like a friendly knock at the door.

And yes, you can hear the ghosts in the room. Fogerty was no longer the voice at the center of Creedence Clearwater Revival—the band whose “deceptively simple” engine had once made American radio feel like a wide-open highway. When “Rockin’ All Over the World” arrived, it arrived with a subtext: I’m still here. I still know how to make this thing move. Billboard’s own trade review captured that sense of return, praising the song as proof that Fogerty was “back,” still carrying the frantic-feel magic that made Creedence matter.

Yet the genius of “Rockin’ All Over the World” is that it refuses to be heavy. It doesn’t argue its importance. It doesn’t “explain” itself. It just gathers people. The lyric is basically a roll call—here we are, here we go—like a bus door folding open at dusk. Its meaning is almost disarmingly generous: rock music as common ground, a place where the week’s bruises don’t get the final word. And when Fogerty hits that hook—“rockin’ all over the world”—he isn’t describing fame. He’s describing connection: the way a chorus can leap from one room to another, from one town to another, until it belongs to everyone.

History proved him right, in a way he couldn’t have fully planned. In 1977, Status Quo cut a tougher, heavier version, and their cover became a genuine UK phenomenon—peaking at No. 3 on the Official Singles Chart. Then, on July 13, 1985, Status Quo opened Live Aid at Wembley with the song—literally kickstarting one of music’s most globally watched days with Fogerty’s chorus. It’s a strange, beautiful fate: a modest U.S. Top 40 hit becoming an international rallying cry once another band strapped it to stadium-sized speakers.

Even Fogerty himself has spoken warmly about that turn of events—acknowledging that the cover’s success came during a “very dark period” in his life and that it helped him feel better, even if many listeners came to associate the song with Status Quo first. That’s the quiet emotional twist behind this record: a song designed to spread light ended up sending some back to its author, at a time when he needed it.

So when you press play on “Rockin’ All Over the World” now, try to hear what it really is: not a slogan, not a product of its era, but a small act of faith. Faith that the night can still be friendly. Faith that a beat can still make the body remember its own happiness. Faith that rock ’n’ roll—simple, stubborn, unpretentious—can still point outward and say, with a grin you can practically hear: all aboard… here we go.