“Summer of Love” remembers 1967 with a wary smile—celebrating the electricity of youth while admitting how quickly ideals can blur into slogans and echoes.

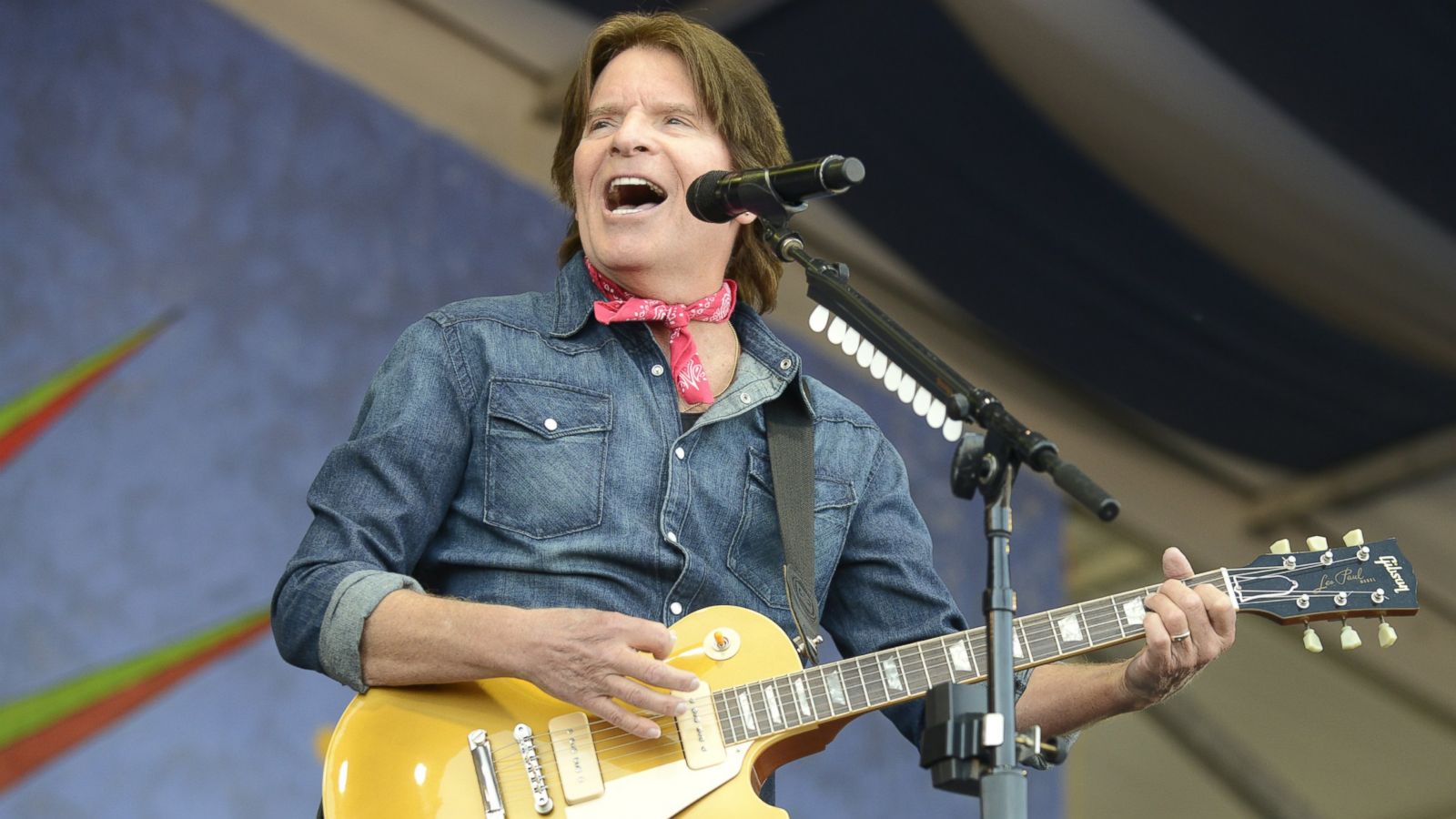

On October 2, 2007, John Fogerty released Revival, and tucked inside it—like a postcard from a complicated decade—was “Summer of Love” (track 7, 3:19). The album itself arrived with real weight: it debuted at No. 14 on the Billboard 200, moving about 65,000 copies in its first week, a strong return that proved Fogerty’s voice still had the power to cut through modern noise. But “Summer of Love” wasn’t the radio spearhead—“Don’t You Wish It Was True” was the first single—so the song’s impact lives less in chart math and more in atmosphere: an album cut meant to be heard, not “launched.”

The story behind the track is written right into its sound. Fogerty deliberately frames “Summer of Love” as a tribute—specifically to Cream and Jimi Hendrix—and the song includes a musical nod to Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love.” Critics caught that immediately, noting the “Cream-like riff” and the way Fogerty borrows the feel of that late-’60s guitar swagger to paint his scene. Even the official presentation of Revival has leaned into this idea, describing the track as “Hendrix-infused,” which is a fair shorthand for its thick, classic-rock bite.

Yet what makes “Summer of Love” linger isn’t the homage—it’s the emotional double-exposure. Fogerty points us to the mythic year of 1967, the moment when “freedom was in the air” and the world seemed young enough to believe it could reinvent itself in real time. That phrase—freedom in the air—isn’t just a lyric; it’s an old scent many listeners can still recall: patchouli and newsprint, sunshine and sirens, the sweet optimism of crowds and the sharp fear of consequences. Fogerty doesn’t treat that era like a museum exhibit, neatly labeled and safely behind glass. He treats it like memory really behaves: bright at the edges, hazy in the middle, and haunted by what came after.

And that’s where his perspective matters. Fogerty is not simply romanticizing the Summer of Love; he’s interrogating it from a later vantage point—after dreams have been tested by decades of politics, war, compromise, and the quiet erosion that time applies to every ideal. On Revival, he was already writing openly about the Iraq War and the Bush era—this was an album willing to argue with history, not just sing about it. In that context, “Summer of Love” reads almost like a reflective sidebar: a look back at the last time the culture felt collectively “young,” and a question—unspoken but heavy—about what we did with that youth.

Musically, the track’s classic-rock muscle is almost sly. The riff says “party,” but the feeling beneath it is closer to unease. It’s the same artistic trick Fogerty has always done well: set the warning inside something catchy enough that you’ll hum it before you fully admit what it’s saying. His gift, since the Creedence Clearwater Revival days, has been to make a song move like a good time while it quietly carries dread in its pockets.

The recording details underline that workmanlike seriousness. Revival was recorded at NRG Recording Studios in North Hollywood, with Fogerty credited as writer and producer, keeping the album’s voice unmistakably his. There’s a certain dignity in that: a veteran artist not chasing younger trends, but shaping modern recordings with the same stubborn identity—guitars, rhythm, and a narrator who refuses to stop paying attention.

So what is “Summer of Love” really about?

It’s about the way we mythologize our own turning points—and the way those myths, over time, can start to feel like old posters: beautiful, faded, and slightly dishonest in their simplicity. Fogerty seems to ask us to remember the thrill without lying about the aftermath. To honor the questions we once dared to ask, while noticing how many of those questions were left unanswered—or answered in ways nobody wanted. The song becomes a kind of late-night conversation with your younger self: affectionate, a little skeptical, and deeply aware that history doesn’t freeze at its prettiest moment.

In the end, “Summer of Love” isn’t nostalgia as comfort. It’s nostalgia as reckoning. A guitar salute to the giants (Cream, Hendrix) paired with a clear-eyed look at what the “summer” promised—and what the years demanded afterward. And maybe that’s why it hits the way it does: because it doesn’t tell you to go back. It tells you to remember honestly… and to notice how the past still hums inside the present, like a familiar riff you can’t quite get out of your head.