“The Dolphins” is a song about searching for something pure and unreachable—hope shaped like a creature you can’t quite prove exists, yet you keep swimming toward anyway.

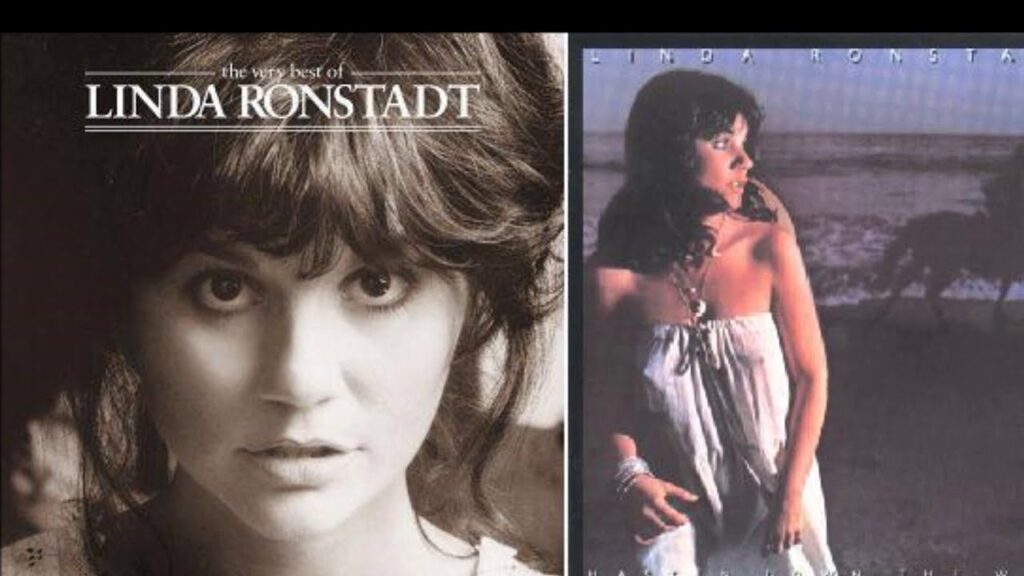

In March 1969, Linda Ronstadt placed “The Dolphins” at the very end of her first fully solo-credited studio album, Hand Sown … Home Grown—as if she wanted the record to close not with certainty, but with a question that lingers after the needle lifts. The album was produced by Chip Douglas, and it captures Ronstadt at that early, searching crossroads where she was told she was “too country” for rock radio and “too rock” for country radio—yet she kept chasing that “California twist” on Nashville feeling anyway. Choosing “The Dolphins”—a folk-rock lament written by Fred Neil—wasn’t a casual cover. It was a statement of taste and temperament: she was already reaching for songs that felt older than their years, songs that carried a bruise and a blessing in the same breath.

Ronstadt’s recording of “The Dolphins” is credited simply to Fred Neil, and on the original album track listing it runs 4:21. (Many modern digital editions list it closer to 4:04, but the LP-era listing remains the clean historical reference point.) What’s equally important, if you care about “rankings at launch,” is that this performance’s chart story is tied to its release format, not to a Hot 100 peak: Ronstadt didn’t break the song as a hit A-side. Instead, it traveled into the world most visibly as the B-side of her March 1969 single “The Long Way Around” / “The Dolphins.” That single is documented as uncharted in U.S. listings—one of those early-career releases that mattered artistically long before it mattered commercially.

To feel what Ronstadt is doing with “The Dolphins,” it helps to understand the song’s origin. Fred Neil first released it in January 1967 on his self-titled album Fred Neil, and it was also issued as a single. The lyric’s famous line—“I’ve been searching for the dolphins in the sea”—has often been read as metaphor rather than marine biology: a sign of yearning for a freedom, a grace, or a lost innocence that keeps slipping away the moment you think you’ve found it. Yet the irony is beautifully human: Neil really was fascinated by dolphins, visiting the Miami Seaquarium in the mid-1960s, and he later co-founded the Dolphin Research Project with Ric O’Barry in 1970 to oppose the capture and exploitation of dolphins. So the song floats in two worlds at once—symbol and lived obsession—and that double meaning gives it its strange, shimmering power.

Ronstadt sings it as if she understands that searching can be both noble and exhausting. There’s no theatrical sobbing here, no attempt to “act” the pain. Instead, she brings that early Ronstadt clarity—pure tone, steady pitch, the kind of voice that sounds honest even when it’s singing a dream. And in 1969, that honesty mattered. Hand Sown … Home Grown was her first album that credited her alone, her first real step out from the group identity of the Stone Poneys into the frightening solitude of being just herself. Putting “The Dolphins” at the end feels like an emotional signature: a young artist admitting that the world “may never change,” yet still daring to hope for something gentler than the world usually offers.

The song’s deeper meaning—especially through Ronstadt—can be heard as a kind of adult coming-of-age. The narrator has seen enough to be disillusioned, but not enough to stop dreaming. That tension is the ache you feel in the best music of the era: a late-’60s awareness that ideals are fragile, paired with the stubborn refusal to let them die quietly. When Ronstadt sings of searching, she doesn’t sound naïve. She sounds determined—like someone who knows that sometimes the only way to remain human is to keep looking for what seems impossible.

And perhaps that’s why “The Dolphins” remains such a quietly beloved corner of her catalog. It wasn’t a hit, not then. It didn’t arrive with a big chart debut. But it arrived with something rarer: a feeling that outlives radio cycles. A voice at the beginning of a long journey, closing her first true solo record with a question that still haunts the air—what if the thing you’re searching for is real, and the search itself is the proof?