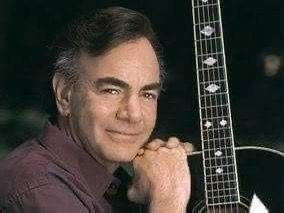

“Missa” is Neil Diamond’s brief, reverent pause inside a larger journey—voices lifted like a candle in the dark, reminding us that faith and longing often speak in the simplest syllables.

To place the most important details up front: “Missa” is a Neil Diamond composition from his sixth studio album Tap Root Manuscript, released October 15, 1970 on Uni, produced by Tom Catalano and Neil Diamond. Within the album’s side-two suite, The African Trilogy (A Folk Ballet), “Missa” appears as the fifth segment, running 2:05. Importantly, it was not released as a single—so there’s no “debut position” for the song itself on weekly singles charts—but the album surrounding it was a genuine commercial success, peaking at No. 13 on the Billboard 200 and earning Platinum certification in the U.S.

Those facts matter because “Missa” isn’t meant to compete for radio space the way “Cracklin’ Rosie” did. It’s meant to change the temperature of the record—one small panel in a larger mural. Tap Root Manuscript famously divides itself in two: pop-rock craft on side one, and then the conceptual, Africa-leaning suite on side two, where Diamond described his ambition in almost theatrical terms: a “folk ballet.” In that context, “Missa” functions like a chapel moment inside a travelogue—short, focused, and strangely cleansing.

What makes “Missa” especially haunting is the way it leans on unaccompanied voices and devotional language rather than the usual Diamond trademarks of big choruses and narrative punchlines. Contemporary credit listings and lyric excerpts show the song using Swahili phrases centered on “Kristo” (Christ) and the announcement of a child being born—images that echo the feel of a Christmas hymn or a communal prayer more than a pop lyric. It’s not sung at you; it’s sung around you, like you’ve stepped into a room where people are already mid-chant and you don’t want to interrupt.

The “story behind” “Missa” is, in many ways, the story behind Diamond’s boldest early-career risk: he was a proven hitmaker by 1970, yet he still chose to devote nearly 19 minutes of an album side to a themed suite that blended African-inspired textures with blues and gospel threads—an approach often noted as unusually early for mainstream Western pop’s flirtation with “world” sensibilities. In that suite, “Missa” arrives after the shimmering “Soolaimón” and before the longer instrumental sweep of “African Suite,” acting like a human bridge: not spectacle, not scenery, but breath and belief.

And that’s the deeper meaning of “Missa”: it suggests that spirituality is not always grand architecture. Sometimes it’s a handful of voices, a repeated name, a promise spoken in a language that may not be yours—and yet the feeling still lands. Even if you don’t understand every word, you understand the posture: heads slightly bowed, hearts slightly opened, the world briefly made smaller and kinder.

There’s also an undertow of nostalgia here that doesn’t rely on “the good old days” as a cliché. “Missa” sounds like an older human instinct resurfacing inside a modern record: the need to gather, to sing together, to mark time with ritual when life feels too loud. In a way, it’s the opposite of pop’s usual demand to be “new.” It’s Neil Diamond reaching backward toward something ancient—toward the idea that a song can be a shared act, not merely a performance.

If you play “Missa” today, it still has that curious power to stop the room. It’s only two minutes, yet it leaves a long shadow—because it reminds us that the most lasting music isn’t always the loudest. Sometimes it’s the piece that sounds like people, unadorned, calling out into the dark and hearing—if only for a moment—that the dark can answer back.