“Sail Away” is CCR’s quiet daydream of escape—a small boat of a song drifting toward open water while the band’s own shoreline was starting to crumble.

There’s a particular kind of ache that only shows up when something big is ending: you don’t always feel dramatic sorrow—you feel a pull toward distance, toward fresh air, toward the idea that you could simply step off the dock and let the world recede. “Sail Away” lives in that feeling. It’s not one of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s radio titans; it’s an album cut, modest in scale, but strangely revealing in context. The song appears on Mardi Gras—CCR’s seventh and final studio album, released April 11, 1972 on Fantasy Records—and it sits on Side Two, track 2, running 2:28. Most importantly, it’s written and sung by bassist Stu Cook.

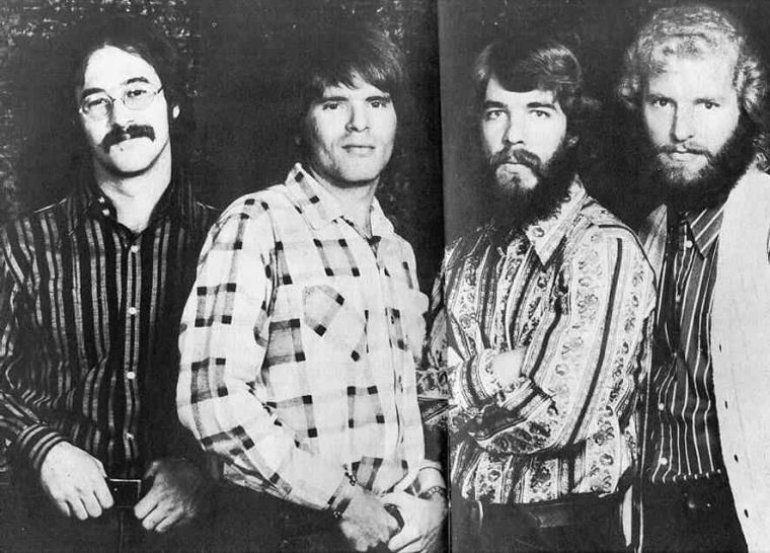

That authorship matters because Mardi Gras was not business as usual. Recorded after the departure of guitarist Tom Fogerty, it was the band’s only studio album as a trio, and—unlike the earlier years when John Fogerty carried nearly all the writing and lead vocals—this record deliberately spread songwriting, singing, and production among the remaining members: Fogerty, Cook, and Doug Clifford. The sessions were “marred by personal and creative tensions,” and the end came swiftly: on October 16, 1972, CCR and Fantasy issued a statement announcing the official disbanding of the group. In other words, when Stu Cook sings “Sail Away,” you’re hearing more than a character in a lyric—you’re hearing a band trying to keep moving while the seams show.

Even the chart story of Mardi Gras has that “last chapter” clarity. The album debuted at No. 63 on the Billboard 200 on April 29, 1972, then climbed to a peak of No. 12. (A respectable commercial life—yet one always followed by the shadow of how the album was received compared to CCR’s near-mythic run just a year or two earlier.) And for your question about “debut position at release”: “Sail Away” itself was not released as a featured single, so it doesn’t have a separate singles-chart debut to cite—its “arrival” is bound to the album’s entry into the world.

So what is this song, really?

On the surface, “Sail Away” reaches for nautical imagery—the captain, the sea, the invitation to leave ordinary land behind. But the deeper emotional meaning is less about geography than about permission. The sea in songs is rarely just water; it’s distance, reinvention, forgetting, starting over. In the CCR universe—where so many stories are set on the road, in the rain, under bad moons—“Sail Away” feels like a gentler cousin to the band’s classic urgency: instead of warning you, it beckons you. It’s the sound of someone looking past the edge of the day and imagining a cleaner horizon.

And then the context presses in—quietly, but insistently. Mardi Gras was assembled in a period where the band’s internal balance had shifted, and the record’s very structure reflects that: equal contributions, separate voices, a group identity that is still “CCR,” yet no longer moving with one single engine. In that light, “Sail Away” becomes almost symbolic: a song about departure, sung by a member stepping forward during an album that—whether anyone admitted it in the studio—was already pointing toward goodbye.

There’s a poignant irony here. The album title Mardi Gras suggests celebration, masks, noise, bright streets. But “Sail Away” is the opposite of noise. It’s a soft exit, a thoughtful glance over the shoulder. It doesn’t try to compete with CCR’s greatest hits; it simply offers another kind of truth—one that feels more adult, more resigned, more familiar to anyone who’s ever watched a chapter close without a clean ending.

That’s why “Sail Away” is worth returning to. Not because it “defines” CCR, but because it shows them from an angle the big singles don’t. It reminds you that even the hardest-working, most plainspoken American rock band of their era could—when the room got quiet—dream about slipping the ropes, letting the tide take over, and trusting that somewhere beyond the shoreline, there might be a gentler kind of morning.