“Hasten Down the Wind” is the sound of loving someone enough to let them go—a quiet, brave goodbye where freedom is granted with a trembling hand, not a slammed door.

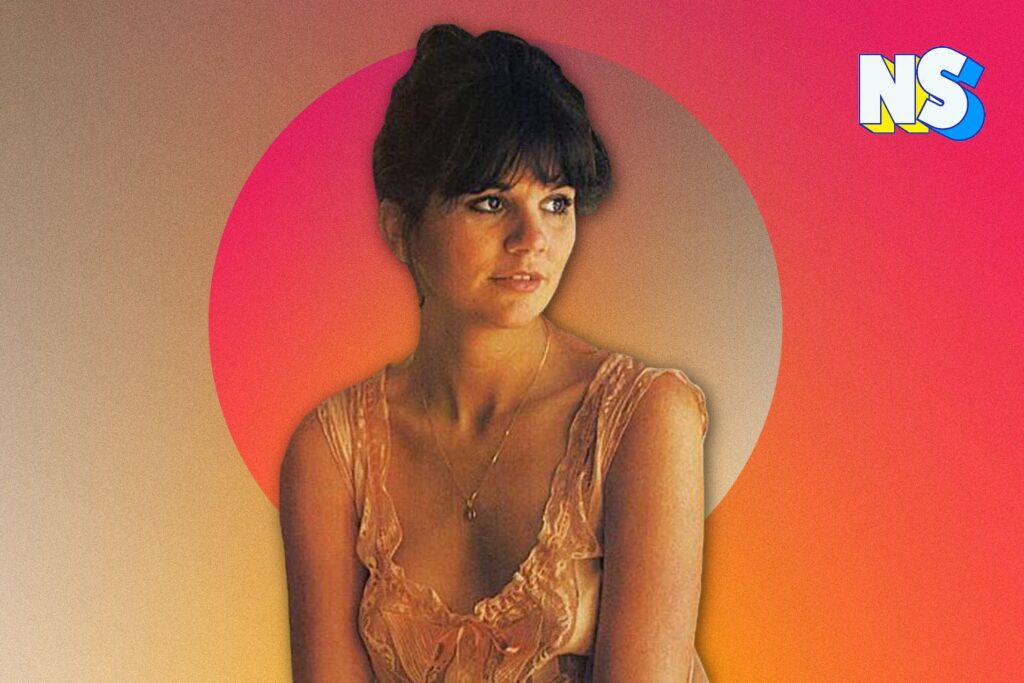

If you’re looking for the essential facts first: “Hasten Down the Wind” is the title track on Linda Ronstadt’s 1976 album Hasten Down the Wind, released August 9, 1976 on Asylum Records and produced by Peter Asher. The album debuted on the Billboard 200 with a debut position of No. 49 (chart date August 28, 1976) and peaked at No. 3, staying a major presence through the season. It also reached No. 1 on Billboard’s country album chart (as summarized in chart research-based listings). The project later earned Ronstadt the Grammy Award for Best Pop Vocal Performance, Female (1977), confirming how fully she had become the voice that could carry rock strength and adult heartbreak in the same breath.

Now, the crucial “ranking at release” detail for the song itself: Ronstadt’s “Hasten Down the Wind” was not released as one of the album’s charting singles, so there is no Billboard Hot 100 debut/peak to cite for her version. The singles pulled from the album were “That’ll Be the Day,” “Someone to Lay Down Beside Me,” “Crazy,” and “Lose Again.” And honestly, that somehow suits the track. It doesn’t behave like a single. It behaves like a private conclusion you arrive at after the bright songs have finished talking.

The story behind the song is one of those moments where musical history turns on an artist’s intuition. “Hasten Down the Wind” was written by Warren Zevon, and Ronstadt recorded it at a pivotal time when she was deliberately spotlighting newer songwriters rather than relying only on familiar standards of country-rock repertoire. What makes it even more striking is that Zevon’s own studio version existed but was not yet released when Ronstadt cut hers—meaning she wasn’t following a hit; she was following a feeling. Zevon’s version would appear as a single from his self-titled major-label debut (released November 1976), produced by Jackson Browne and credited to Zevon’s widening circle of L.A. believers.

Ronstadt’s recording also carries a wonderful piece of 1970s California DNA: Don Henley sings harmony vocals on the track, and the strings were arranged and conducted by David Campbell. (If you’ve ever wondered why the song feels like it’s lit from behind—warm, but with a shadowed edge—that combination is part of the answer.)

On the album’s original track list, “Hasten Down the Wind” closes Side One (track 6, about 2:40), and that placement is pure storytelling. You spend the side moving through longing, second-guessing, old records of the heart—then you arrive here, where the relationship is no longer a question. It’s a decision.

Lyrically, Zevon doesn’t write a breakup as a fight; he writes it as a slow recognition of incompatible weather. A woman insists she needs to be free; a man can’t understand—until he does. She is “so many women,” he can’t find the one who was his friend; he’s “hanging on to half a heart,” but he can’t have “the restless part.” That phrase—the restless part—is the song’s quiet knife. Because it names what so many couples can’t admit without shame: sometimes love isn’t defeated by cruelty; it’s defeated by motion. By a spirit that cannot stay still without feeling it is dying.

What Linda Ronstadt does with that writing is something she did better than almost anyone of her era: she makes the narrator’s surrender sound both tender and devastated, as if he’s trying to be noble even while he’s bleeding. She doesn’t oversell it. She doesn’t “act” the heartbreak. She sings it like a person who has replayed the same conversation so many times that the voice has grown calm—while the soul has not. And because the arrangement never bullies the lyric, every small turn of the melody lands like a thought you didn’t mean to say out loud.

There’s a broader, almost cultural meaning in the track, too. In the mid-’70s, the mythology of “freedom” was everywhere—freedom as romance, freedom as selfhood, freedom as the great American promise. “Hasten Down the Wind” asks the cost of that promise in human terms: Who pays for freedom when the bill comes due inside a relationship? And it answers without preaching. It simply shows two people reaching a point where staying becomes a kind of lie. The title itself is a blessing disguised as dismissal: go, quickly—before we turn love into resentment; go, while I can still wish you well.

It’s telling that this song sat on an album that was both commercially mighty and emotionally weightier than many expected. Hasten Down the Wind wasn’t just another hit machine; it was Ronstadt deepening her craft as a curator of American songwriting—pulling voices like Warren Zevon into the mainstream room, letting listeners discover a writer’s sharp tenderness through her famously clear instrument.

In the end, “Hasten Down the Wind” is not the kind of track that begs to be remembered by chart numbers. It prefers a different kind of permanence: the permanence of recognition. That moment when you realize you cannot hold someone and honor them at the same time—and the only loving thing left to do is open your hand, look away, and let the wind do what it was always going to do.