“Hello Mary Lou” is not just a greeting to first love, but a gentle knock on the door of memory, where youth still waits, smiling

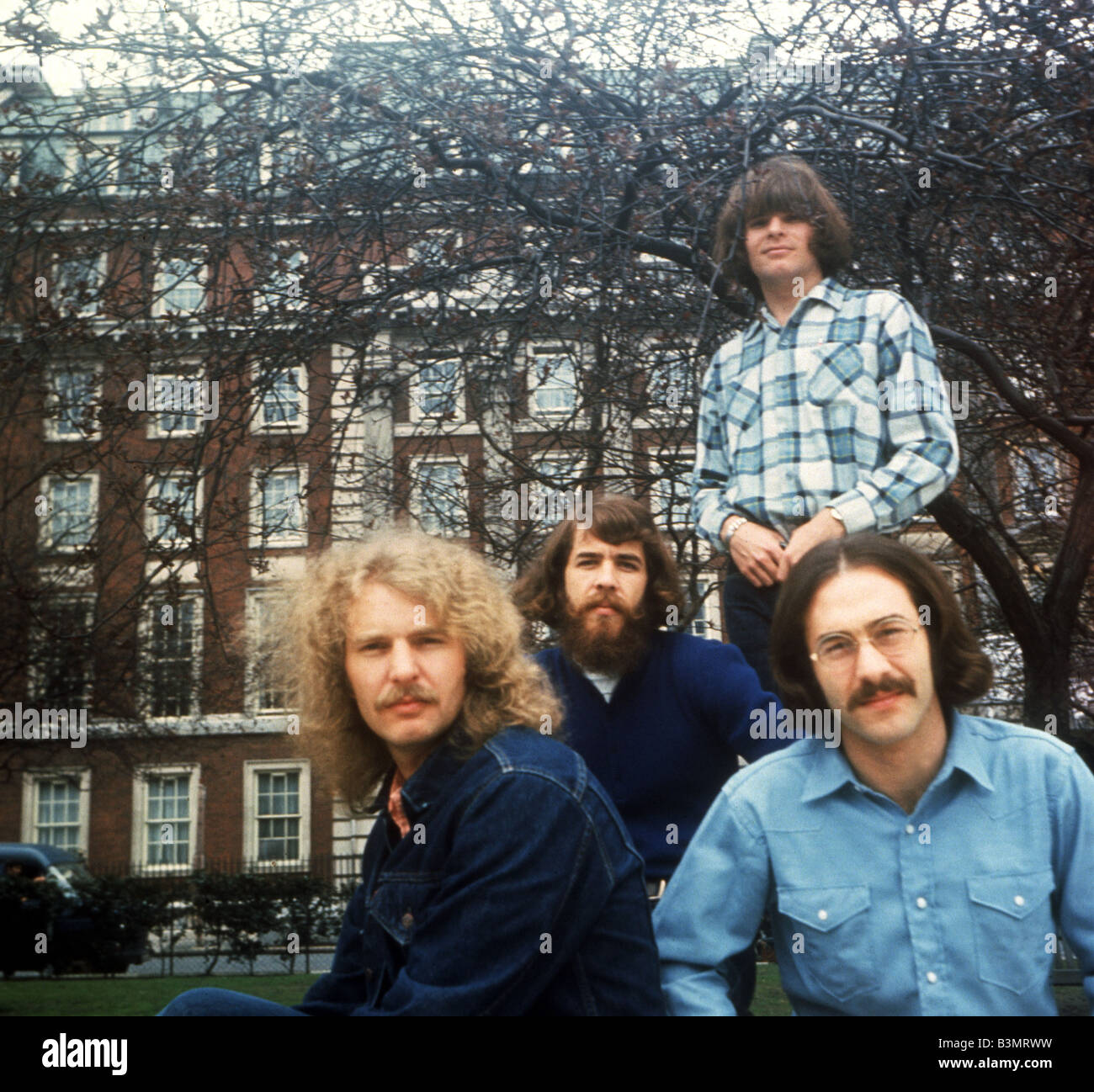

When Creedence Clearwater Revival recorded “Hello Mary Lou”, they were already standing at the edge of their own story. The song appeared in 1972 on Mardi Gras, the final studio album released under the Creedence Clearwater Revival name. By then, the band’s internal fractures were no secret, yet this recording sounds strangely untouched by conflict. Instead, it feels like a last glance backward—toward innocence, melody, and a time when a simple love song could still feel complete.

“Hello Mary Lou” itself was never meant to be revolutionary. Written in 1961 by Gene Pitney, the song first became a rock-and-roll staple through Ricky Nelson, whose version captured the buoyant optimism of early-’60s youth culture. When Creedence revisited it more than a decade later, the world—and the band—had changed. What remained was the song’s melodic clarity, now filtered through a warmer, more reflective lens.

Upon release, “Hello Mary Lou” was issued as a single in the UK and parts of Europe, where it resonated strongly with listeners. In Britain, it reached No. 2 on the UK Singles Chart, an impressive achievement for a band already perceived as nearing its end. In the United States, the song was not promoted as a major single, yet it found steady life on radio and within the album itself, quietly reaffirming Creedence’s instinct for timeless material rather than momentary trends.

What makes Creedence’s “Hello Mary Lou” so affecting is its tone. This is not the wide-eyed infatuation of the early rock era, nor the swagger of late-’60s counterculture. Instead, it occupies a middle space—gentle, almost tender. John Fogerty’s vocal delivery is relaxed, conversational, as if he is telling a story he knows by heart. There is no rush, no urgency. The rhythm section settles into an easy sway, allowing the melody to do what it has always done best: carry feeling without excess.

Within the context of Mardi Gras, the song takes on an added layer of meaning. The album itself was born from compromise, with songwriting duties divided among band members in an attempt to hold things together. Against that backdrop, “Hello Mary Lou” feels like a shared memory everyone could agree on—a song from before arguments, before pressures, before success became heavy. It is telling that the band chose to look backward rather than forward at this moment. Sometimes nostalgia is not escapism, but survival.

Lyrically, “Hello Mary Lou” remains disarmingly simple. There is no drama, no conflict, only admiration and longing. Yet simplicity does not mean shallowness. In Creedence’s hands, the song becomes a meditation on first impressions—the kind that stay with you long after life has complicated everything else. The repeated greeting is not merely flirtation; it is recognition. A reminder of how quickly a single moment can anchor itself in memory.

As the final chapters of Creedence Clearwater Revival were being written, “Hello Mary Lou” stood as a quiet counterpoint to the band’s more urgent, socially charged work. It did not protest, warn, or accuse. It simply remembered. And perhaps that is why it endures. In a catalog filled with river imagery, restless motion, and American unease, this song pauses long enough to smile.

Today, “Hello Mary Lou” remains one of those recordings that feels permanently suspended between past and present. It carries the warmth of early rock and roll, the craftsmanship of a seasoned band, and the unspoken sadness of an ending close at hand. It reminds us that sometimes the most meaningful goodbyes are disguised as greetings—and that a simple “hello” can echo long after the music fades.