A Defiant Cry Against Privilege, Echoing Through the Halls of Power

When Creedence Clearwater Revival took the stage at London’s Royal Albert Hall on April 14, 1970, they were not merely a band performing their hits—they were ambassadors of American unrest, exporting the raw tension of their homeland to one of the most hallowed venues in rock history. That night’s rendition of “Fortunate Son”, captured live and later immortalized in the collection At The Royal Albert Hall, distilled everything that made the group both beloved and incendiary: lean instrumentation, unfiltered urgency, and a righteous, working-class fury that cut through the fog of polite society. Originally released in 1969 on the album Willy and the Poor Boys, the song had already soared into the Top 5 of the Billboard Hot 100. By the time it reverberated off the ornate arches of the Albert Hall, it was no longer just a chart hit—it had become a declaration.

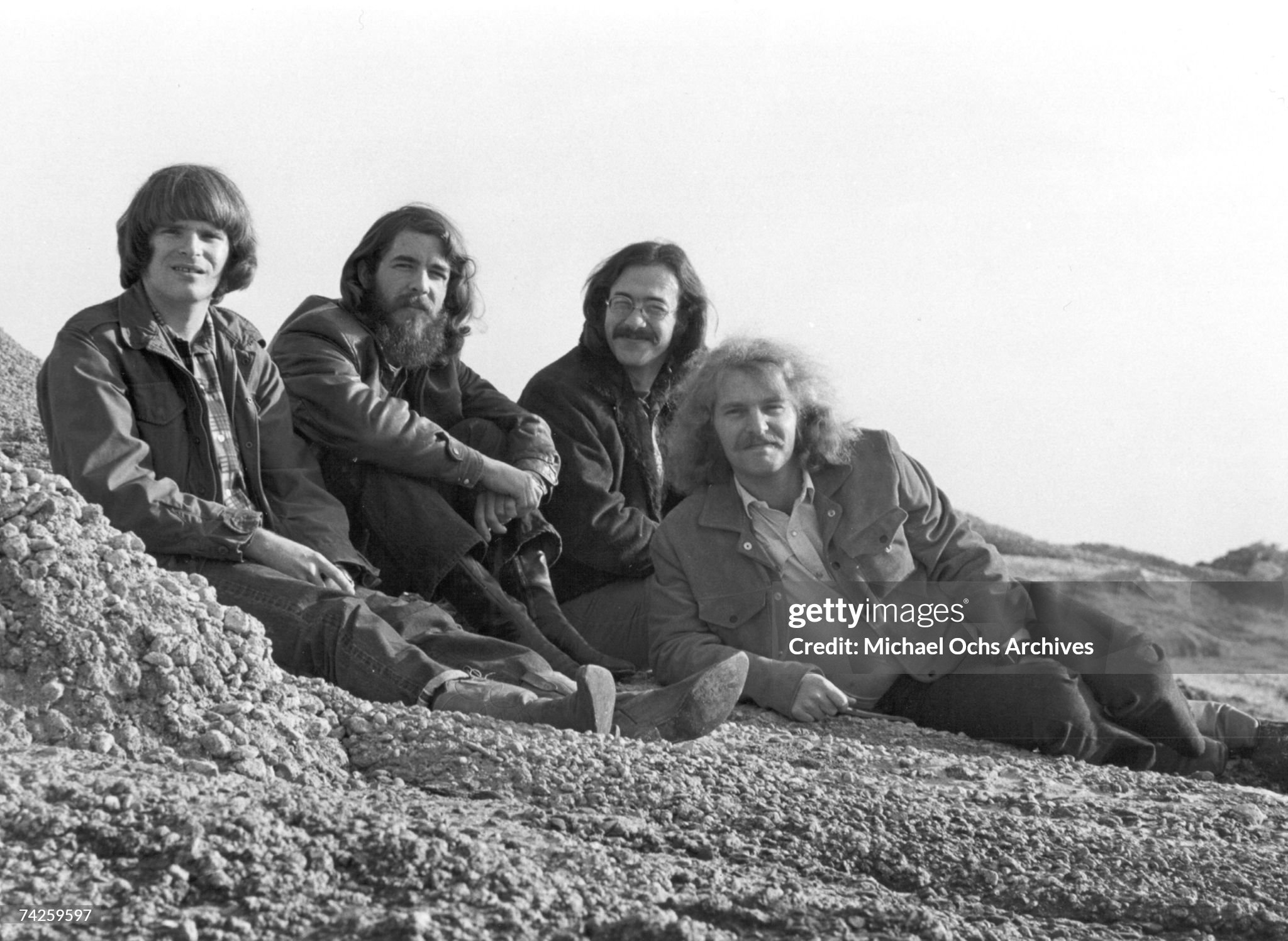

At its core, “Fortunate Son” is an anthem of disillusionment with inherited privilege and political hypocrisy. Written by John Fogerty, its biting tone emerged amid the Vietnam War, when American youth were being drafted in droves while the sons of senators and industrialists found ways to stay home. The song channels that inequity into two minutes of blistering rock and roll—each riff a clenched fist, each word a spark of rebellion. But what sets this performance apart from its studio counterpart is its immediacy: stripped of overdubs and polished production, the song becomes something rawer and more volatile. Fogerty’s voice tears through the hall like a rallying cry; Doug Clifford’s drumming pounds like boots on parade ground asphalt; Stu Cook’s bass holds steady beneath Tom Fogerty’s rhythm guitar, anchoring chaos in purpose.

In London, before an audience far removed from America’s turmoil yet enthralled by its cultural firestorm, Creedence Clearwater Revival brought working-class American truth to imperial marble. The Royal Albert Hall, accustomed to symphonies and decorum, trembled under their swamp-rock conviction. The irony was almost poetic—an anti-elitist protest song roaring inside one of Britain’s grandest symbols of establishment prestige. Yet that contrast heightened its potency. The performance transformed “Fortunate Son” into something nearly universal: a protest not bound by borders but by conscience, a song that calls out inequality wherever it festers.

Over half a century later, this live version remains one of rock music’s most visceral confrontations with class and power. Its chords still carry dust from factory floors and echoes from protest marches; its message still stings because its truth remains unresolved. “Fortunate Son” endures not just as an artifact of an era but as a perpetual alarm bell—one that refuses to let comfort drown out conscience.