“Junked Heart Blues” is David Cassidy singing from the scrapyard of love—where hope still sparks, even after the engine has been written off.

The first thing to say—plainly, and with respect for the record’s true nature—is that “Junked Heart Blues” was never a conventional hit single with a neat “debut at No. X” story. It’s a deep-cut confession from one of Cassidy’s most complicated, half-hidden eras: recorded for his RCA album Gettin’ It in the Street, released in Germany and Japan in November 1976, while the planned U.S. issue was shelved and only turned up later when already-pressed copies were dumped on the American market in July 1979. In that sense, the song’s “launch” wasn’t a trumpet blast—it was more like a message in a bottle, washed ashore years later in cut-out bins and collector circles.

Still, there is a small, telling chart-adjacent footprint around this period. The album’s title track was issued as a single and grazed the U.S. listings at No. 105 on Billboard’s Bubbling Under—a detail that hints at why RCA lost patience. Meanwhile, “Junked Heart Blues” itself did circulate as a B-side in Germany, paired with “January” on RCA catalog PB 9139 (a discography entry that underscores how regional and piecemeal Cassidy’s mid-’70s release strategy became).

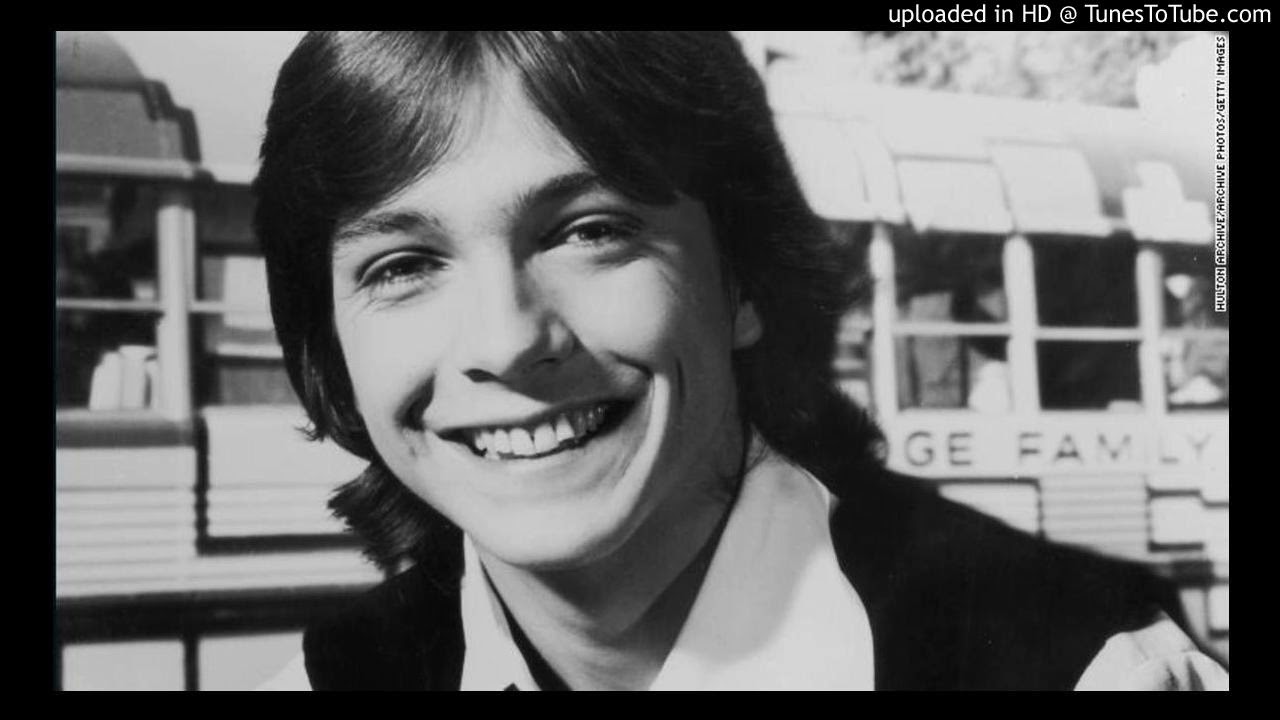

Those facts matter because they shape how you hear the song. “Junked Heart Blues” is credited simply to David Cassidy—he wrote it himself. That alone makes it feel different from the early years when his voice was often placed into other people’s framing. Here, the framing is his. And on Gettin’ It in the Street, he wasn’t merely the face on the sleeve; he was also the co-producer (credited alongside Gerry Beckley of America), trying to steer his own musical narrative at a moment when the industry wasn’t sure what to do with him anymore.

So what’s the song’s emotional core?

It’s right there in the title: “Junked Heart Blues.” Not “broken heart,” not “lonely heart”—but junked, like a beloved machine left behind a fence, deemed too damaged to be worth repairing. The phrase carries shame and resignation, but also a stubborn mechanical poetry: even a “junked” heart can still hum, still ache, still insist it has one more ride left in it. In the lyric fragments that circulate in discographies and song references, you feel the narrator teetering between bravado and pleading—reaching high, almost making it, then tumbling back into that familiar blue.

Musically, it’s a telling choice for Cassidy. In 1976 he was pushing hard toward a tougher, road-worn identity—less teen-idol sheen, more rock-and-roll survivor. That entire album is framed in rock terms: the title track even features guitar work by Mick Ronson, a name that signals Cassidy’s ambitions were pointed firmly at credibility, not nostalgia. Against that backdrop, “Junked Heart Blues” feels like the late-night corner of the record—the part where the lights are lower and the performance becomes less about proving something and more about admitting something.

And what Cassidy admits—quietly, without melodrama—is that heartbreak isn’t always dramatic. Sometimes it’s repetitive. It comes back like a familiar ache in old weather. That’s why “blues” is the perfect word here: not just a style, but a cycle. The song doesn’t sound like a grand finale to love; it sounds like the weary middle chapter—when you’re still asking someone to stay, still asking yourself to be worth staying for.

There’s also a kind of tragic irony in the album’s release history. Gettin’ It in the Street became, in practice, a record that slipped away from the mainstream—released abroad, withheld at home, then resurfacing later almost by accident. That mirrors the emotional logic of “Junked Heart Blues” itself: the fear of being set aside, the dread of being treated as yesterday’s model, the longing to be taken seriously now, while the heart is still beating.

Maybe that’s why the song has held on for listeners who go digging past the obvious hits. It captures a particular human moment—when pride has been sanded down, and what’s left is a plain request: don’t give up on me while I’m still trying. In the end, “Junked Heart Blues” doesn’t need chart fireworks to be important. It’s important because it sounds like a real person standing in the shadows of his own fame, holding out something honest and bruised, and hoping—just hoping—that someone will hear the life still ticking inside it.