“Effigy” is CCR’s slow-burning protest hymn—grief and anger carried on a weary groove, as if the nation itself is watching a fire and wondering what will be left when it goes out.

If Creedence Clearwater Revival often feel like the sound of motion—rivers running, wheels turning, work getting done—then “Effigy” is the moment the engine idles and the night air turns cold. It closes their fourth album, Willy and the Poor Boys, released by Fantasy Records on October 29, 1969, an album that would peak at No. 3 on the US Billboard 200. And there, at the very end of a record that spends so much time smiling through grit, “Effigy” arrives like a hard truth nobody wanted to say at the party: it is 6:26 of smoke, suspicion, and moral fatigue, written (and produced, like the album) by John Fogerty.

The title alone carries centuries of meaning. To burn someone in effigy is to admit you feel powerless in the ordinary channels—so you turn your rage into a symbol and set it alight. Fogerty wasn’t writing in a vacuum; he was writing in late 1969, when the United States was raw with the Vietnam War, protests, backlash, and that terrible feeling that the country was arguing in two different languages. Years later, Fogerty explained that “Effigy” was sparked by his reaction to President Richard Nixon dismissing anti-war demonstrators—walking out, sneering, and heading back inside as if nothing outside the gates could touch him. You can hear that insult—casual, presidential, and chilling—inside the song’s atmosphere. It’s not just anger. It’s the sick realization that your outrage may be treated as background noise.

What makes “Effigy” so haunting is how it refuses the easy pleasures CCR delivered so effortlessly elsewhere. On Willy and the Poor Boys, you get the street-corner cheer of “Down on the Corner,” the bright bounce of older folk material, even playful instrumentals—moments that feel like human beings trying to keep the lights on. But “Effigy” is the final room in the house, the one with the door half-closed. It’s the album’s shadow, and it matters that it comes last: a closing argument, a final look across the shoulder before the record ends.

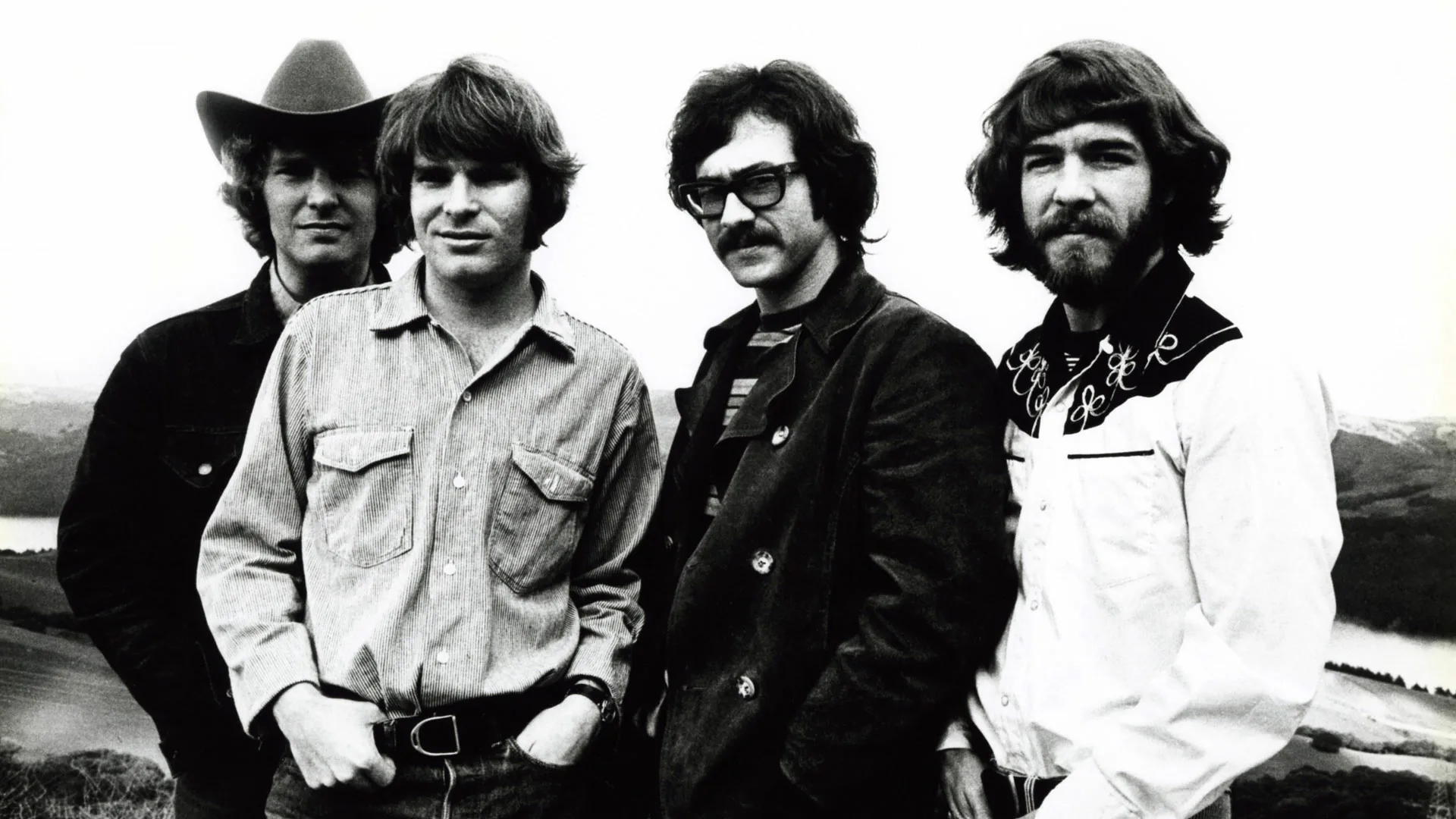

Musically, it’s built like an inexorable march—slow, minor-key, and stubbornly unpretty. Fogerty sings as if he’s reporting from a distance, not because he’s detached, but because he’s trying to keep his voice steady while the ground moves under him. The band—Tom Fogerty, Stu Cook, Doug Clifford—plays with that special CCR discipline: no clutter, no indulgence, just pressure applied evenly until the tension becomes its own melody. This is protest music that doesn’t wave banners; it tightens its jaw.

And the lyric’s central images cut deep because they’re so blunt. An effigy burns. A “chief” is invoked. A “town” is threatened. The language is intentionally elemental—fire, authority, crowd—because the feeling is elemental too: the sense that civic life has become a ritual of intimidation and denial. What the song mourns, underneath its anger, is not only policy. It mourns a fracture of empathy, the moment a nation stops listening to itself and starts performing contempt.

That’s why “Effigy” has grown more resonant with time. It isn’t dated by slogans. It’s animated by something older and sadder: the fear that power will always outlast protest; the hope—stubborn, nearly embarrassed—that it won’t. In Fogerty’s telling, even the act of symbolic burning feels less like triumph than desperation. The fire doesn’t warm you. It only proves you’re cold.

So when you return to “Effigy” now, it doesn’t merely sound like a political artifact tucked onto the end of a classic album. It sounds like the conscience of CCR speaking in its lowest register. The hits may still light up the room, but this is the track that lingers after the lights go down—a reminder that rock and roll, at its best, wasn’t only about escape. Sometimes it was about staying awake, staring at the smoke, and admitting—quietly, plainly—that the world you love can frighten you, too.