“Molina” is urgency without explanation—three minutes where motion replaces answers, and the night feels too tight to slow down.

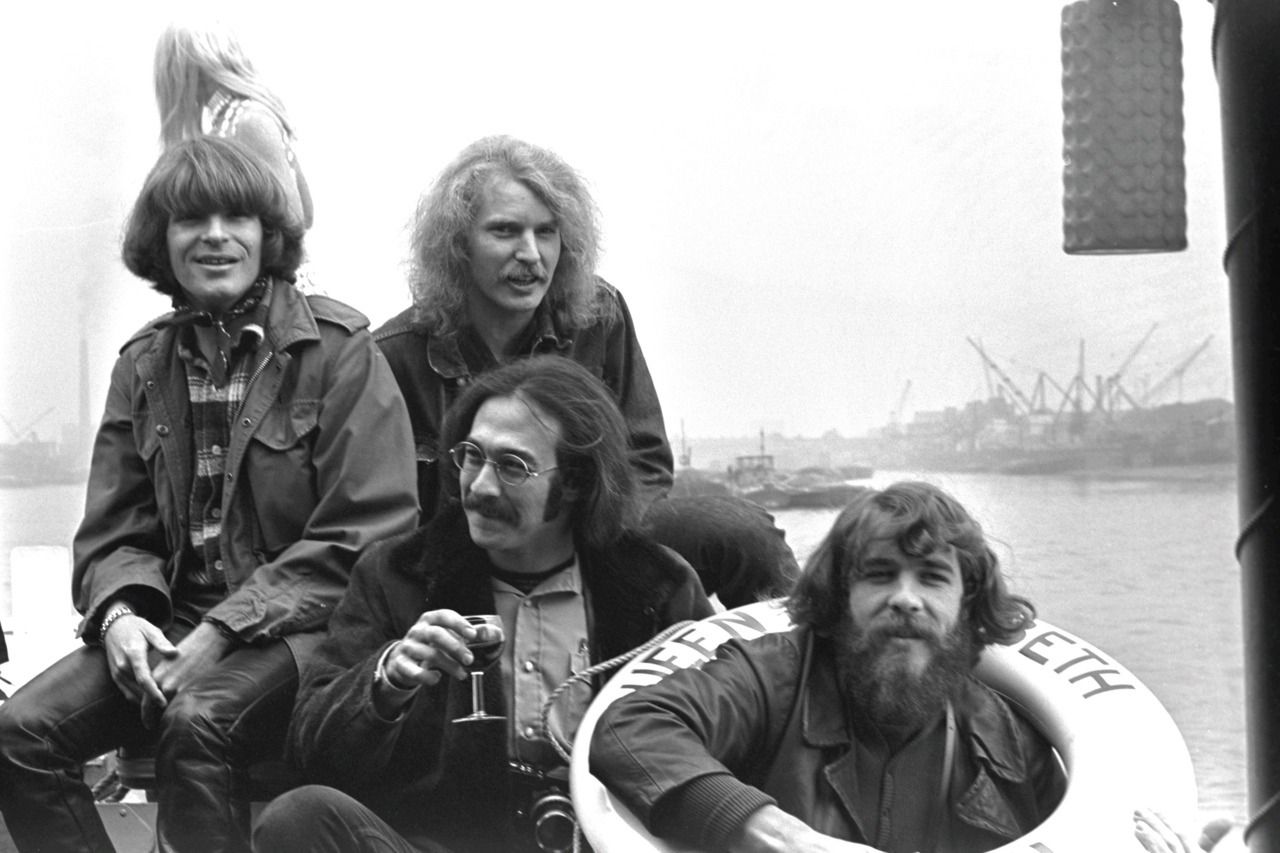

“Molina” sits in a very specific, powerful place within the story of Creedence Clearwater Revival. It is not a song from their collapse, nor a farewell gesture. It belongs to a moment when CCR were still sharp, focused, and creatively confident. Written by John Fogerty and released in December 1970 on the album Pendulum, “Molina” reflects a band still moving forward, even as the road ahead was beginning to curve in unfamiliar ways.

Pendulum itself is a crucial record. It followed Cosmo’s Factory, one of the most successful albums of the era, and it showed CCR quietly expanding their sound—adding keyboards, stretching arrangements, letting the studio breathe—without losing their muscular core. The album reached No. 5 on the Billboard 200, and while it produced major hits like “Have You Ever Seen the Rain” and “Hey Tonight,” “Molina” remained an album track, almost hidden in plain sight. That’s part of its mystique. It doesn’t ask to be chosen; it waits for the listener to stumble into it.

From the first moments, “Molina” sounds like something already in progress. There is no invitation, no setup. The rhythm jumps forward immediately, as if the band arrived late and had no intention of apologizing. Fogerty’s vocal is tense and clipped, delivering fragments rather than explanations. “Hey tonight, gonna be tonight” repeats not as romance, but as pressure—a deadline, a moment that cannot be postponed.

The name Molina is never defined, and that is the song’s greatest strength. Fogerty gives us no biography, no backstory, no emotional map. The name functions like a signal—something meaningful to the singer, but deliberately withheld from the listener. Over the years, this has fueled endless speculation: a real person, a code name, a symbol of pursuit, even a sense of being watched or chased. Fogerty himself has never offered a definitive explanation, and the refusal feels intentional. The song isn’t about who Molina is. It’s about the feeling that someone—or something—is close enough to make you move faster.

Musically, “Molina” is CCR discipline at its peak. The rhythm section pushes forward with no looseness, no indulgence. The guitar lines are economical, sharp, and functional. Nothing wanders. Everything serves momentum. This is not the swampy sprawl of earlier tracks like “Born on the Bayou,” nor the epic tension of “Ramble Tamble.” It is compressed energy—rock ’n’ roll stripped of atmosphere and left with pure intent.

What makes the song especially compelling is its emotional ambiguity. It isn’t joyful, but it isn’t dark either. It exists in a narrow emotional corridor: urgency without panic, excitement without pleasure. That in-between space gives “Molina” its nervous edge. It feels like a song written by someone who knows they shouldn’t stop moving—but also doesn’t quite remember why they started.

Within CCR’s catalog, “Molina” stands as a reminder that Fogerty could create intensity without grandeur. He didn’t need social commentary, protest lyrics, or Americana imagery here. He relied instead on rhythm, repetition, and restraint. The song trusts the listener to feel what it refuses to explain.

With time, “Molina” has aged into something even more interesting. Heard now, it feels like a document of pressure—of life moving too fast to process, of nights where instinct takes over because reflection would slow you down. It captures a truth that doesn’t belong to any one era: sometimes we move not because we know where we’re going, but because standing still feels dangerous.

In the end, “Molina” doesn’t resolve. It doesn’t open up. It doesn’t tell its story. It simply moves—and stops when the tape runs out. That lack of closure is not a flaw. It’s the point. Like a car disappearing down a dark road, the song leaves you with motion, noise, and questions echoing behind it. And that restless echo is exactly why “Molina” remains one of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s most quietly compelling tracks.