“High Sierra” is a song about emotional altitude—how love can lift you into thin, dazzling air, and how the fall back to earth can leave you quietly breathless.

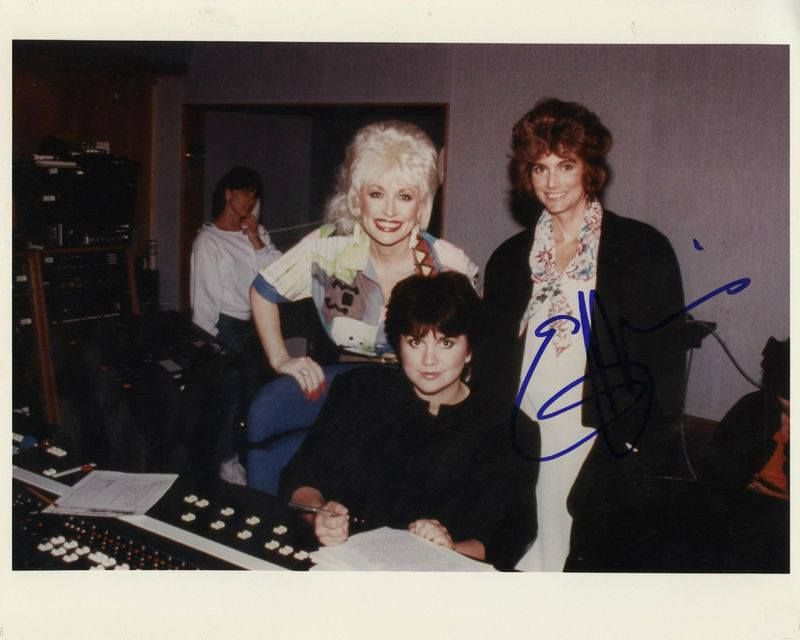

Right up front, the hard facts matter because they give this performance its bittersweet glow. “High Sierra” is the opening single (and track two) from Trio II by Dolly Parton, Linda Ronstadt, and Emmylou Harris—an album released on February 9, 1999, though the recordings themselves dated back to 1994. The song was written by Harley Allen and produced by the meticulous, clear-eared George Massenburg. In Canada, it managed a small but telling chart footprint: on RPM’s Country 100 it reached a peak of No. 90; on the March 8, 1999 issue it sat at No. 90, listed as its second week on the chart (with its prior-week position shown as No. 91, meaning that’s effectively its debut ranking). A week later, March 15, 1999, it had slipped to No. 96. Not a blockbuster—more like a faint radio signal you’re grateful you caught.

And maybe that’s the perfect way for “High Sierra” to live: not as a trophy, but as a moment of atmosphere.

The backstory carries its own kind of ache. After the enormous success of their first collaboration (Trio, 1987), the three women recorded the Trio II material in 1994, but label disputes and the sheer difficulty of aligning three major careers kept the album shelved for years. In the meantime, Linda Ronstadt remixed several songs—without Dolly Parton’s vocals—and released them on her 1995 album Feels Like Home, including “High Sierra.” So when Trio II finally arrived in 1999, it didn’t feel like “new” music in the usual industry sense. It felt like something rescued: a letter written long ago, delivered late, and somehow more moving for the delay. Even the rollout reflected that odd, in-between space—“High Sierra” was sent to adult contemporary stations in January 1999 ahead of the album, and it even drifted into country radio “by mistake,” where it picked up some airplay.

That tension—between intention and accident, between timing and timelessness—sits inside the song itself. “High Sierra” is built on contrast: height and hurt, beauty and bruise. The very phrase “High Sierra” suggests a place where the air is stunningly clean and the view goes on forever… but where you can also get lost, or cold, or stranded if you misjudge the weather. The song’s emotional geography works the same way. It paints love as something that can elevate you past your usual limits—higher than you thought you could feel—until passion turns, quietly but decisively, into pain.

A wonderful detail is how the trio uses voices the way a landscape uses light. Ronstadt often carries the emotional “front” of the song, and writers have noted how she embodies the character immediately—“so much passion turned to pain”—before the harmonies gather around her like weather moving across a ridge. Parton and Harris don’t compete for the spotlight; they reinforce it, giving the narrative a communal gravity, as if heartbreak isn’t merely a private injury but something shared, understood, survived.

And Harley Allen’s authorship matters here. He wasn’t writing novelty scenery; he was writing lived feeling, and later commentary around his work points to how “High Sierra” came from his earlier years—songwriting that carried the stamp of a real, traveled life. In Trio II, that life meets three interpreters who know exactly how to sing the difference between drama and truth. They sing it with restraint. With adult stillness. With the kind of control that doesn’t hide emotion—it focuses it.

So if you ever wondered why a song can chart modestly yet feel enormous, “High Sierra” is your answer. It isn’t trying to conquer the room. It’s trying to describe the room inside you—the one where old love echoes, where memory has altitude, where you can still feel the thin air of what once lifted you… and the slow, careful return to ground.