“Centerfield” is a joyous plea for a second chance—baseball on the surface, but underneath it’s the sound of a man stepping back into the light, asking to be trusted with the next play.

When John Fogerty released “Centerfield” in 1985, it arrived with the kind of confidence that only comes after silence—after the long, private years when an artist is still an artist, even if the world can’t hear him. On the charts, the song’s first footsteps were modest but unmistakable: it debuted on the Billboard Hot 100 at No. 71 (chart dated May 25, 1985) and climbed to a peak of No. 44. Yet rock radio understood its heartbeat immediately; the track reached No. 4 on Billboard’s rock chart (then Top Rock Tracks). And hovering above it all was the bigger triumph: the comeback album Centerfield—released January 14, 1985—went all the way to No. 1 on the Billboard 200 (with its week at the top dated March 23, 1985).

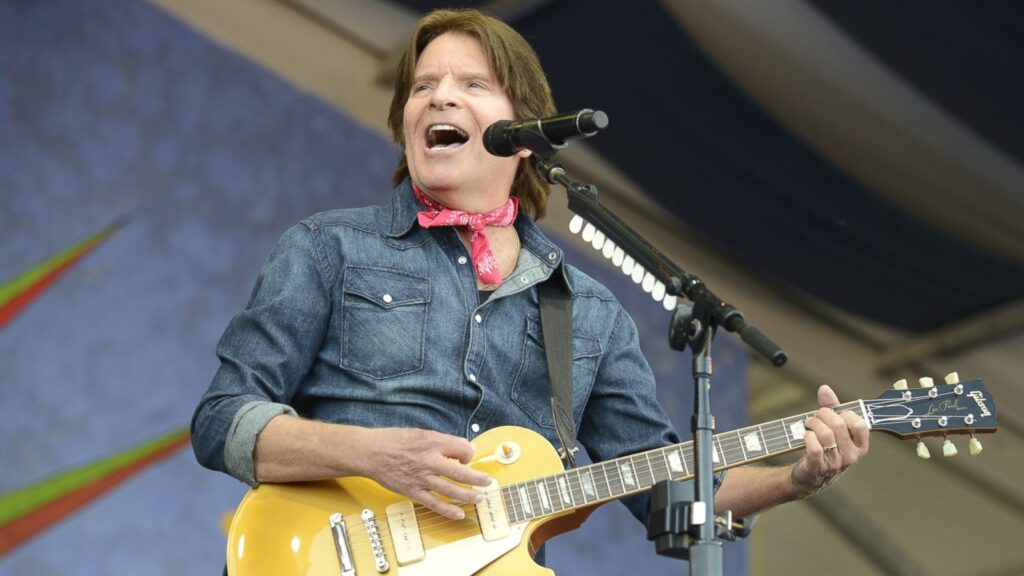

That context matters, because Centerfield wasn’t a casual “next record.” It was a return after years of frustration and legal wrangling tied to his Creedence Clearwater Revival legacy—years that pulled him away from the public, and nearly away from the joy of making records at all. When he finally came back, he did it in the most Fogerty way possible: intensely hands-on, self-reliant, a one-man band chasing a sound in his head. As Mix Online recounts, he went into The Plant Studios in Sausalito in late 1984 and—once again—chose to play the instruments himself, a strikingly direct, almost solitary kind of craftsmanship.

So why baseball? Because baseball, in Fogerty’s imagination, was never merely a sport. It was lore—names spoken like saints in a family living room. In a wonderfully demystifying piece for the Los Angeles Times, Brian Cronin explains that the popular legend about Fogerty writing the song after watching the 1984 MLB All-Star Game from the centerfield bleachers is false—even though Fogerty did attend the game. The deeper truth is more poetic: Fogerty had been moving toward these songs already, rediscovering his muse and writing the album’s material before recording began. The “center field” idea—its “spotlight,” its cosmic feeling of being placed right in the middle of things—was the perfect symbolic doorway for a man returning to his own career.

Listen closely and you can hear how “Centerfield” works on two levels at once. On its face, it’s a bright, uncomplicated day-game anthem: “Put me in, coach—I’m ready to play today.” The handclaps feel like a dugout ritual; the groove moves like cleats over packed dirt. But Cronin notes Fogerty’s own explanation: the lyric also functions as a metaphor—self-motivation at the start of an endeavor, the moment you decide you’ll meet the challenge rather than watch from the sidelines. That’s why the song doesn’t age like a novelty. It isn’t really about baseball trivia, even as it lovingly salutes Willie Mays, Ty Cobb, and Joe DiMaggio; it’s about readiness, about asking life to stop doubting you.

There’s also a gentle ache inside its cheer. The narrator isn’t bragging—he’s pleading, grinning through nerves. That tone is the secret ingredient. Plenty of songs celebrate victory; far fewer capture the trembling second before the gate opens, when you’re not yet a hero—just someone who still believes he can be useful.

And then history did what history sometimes does: it turned a single into a tradition. “Centerfield” became a fixture at ballparks and broadcasts, a kind of unofficial roll call for spring and optimism. By 2010, its bond with the game was so complete that it was honored at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and it’s associated with Cooperstown in a way rock songs almost never are. In other words, what began as one man’s comeback record quietly became part of America’s seasonal memory—played when the grass returns, when the air changes, when it feels possible again to step back into your own story and say, without apology: put me in.