“Play Me” is Neil Diamond’s most intimate kind of seduction—a love song that treats two people like music itself: one the melody, one the instrument, both unable to resist the next note.

When Neil Diamond released “Play Me” in 1972, it didn’t arrive with the thunderclap certainty of a No. 1—yet it climbed with the steady confidence of a song that knew it would be remembered. On the Billboard Hot 100, it debuted at No. 87 and ultimately rose to a peak of No. 11. On Billboard’s Easy Listening chart (now Adult Contemporary), it reached No. 3, confirming what listeners already felt: this was Diamond in his natural element, writing straight to the heart without raising his voice. In the UK, it registered more modestly, peaking at No. 55—a reminder that even “big” songs can have different destinies depending on which radio skies they’re born under.

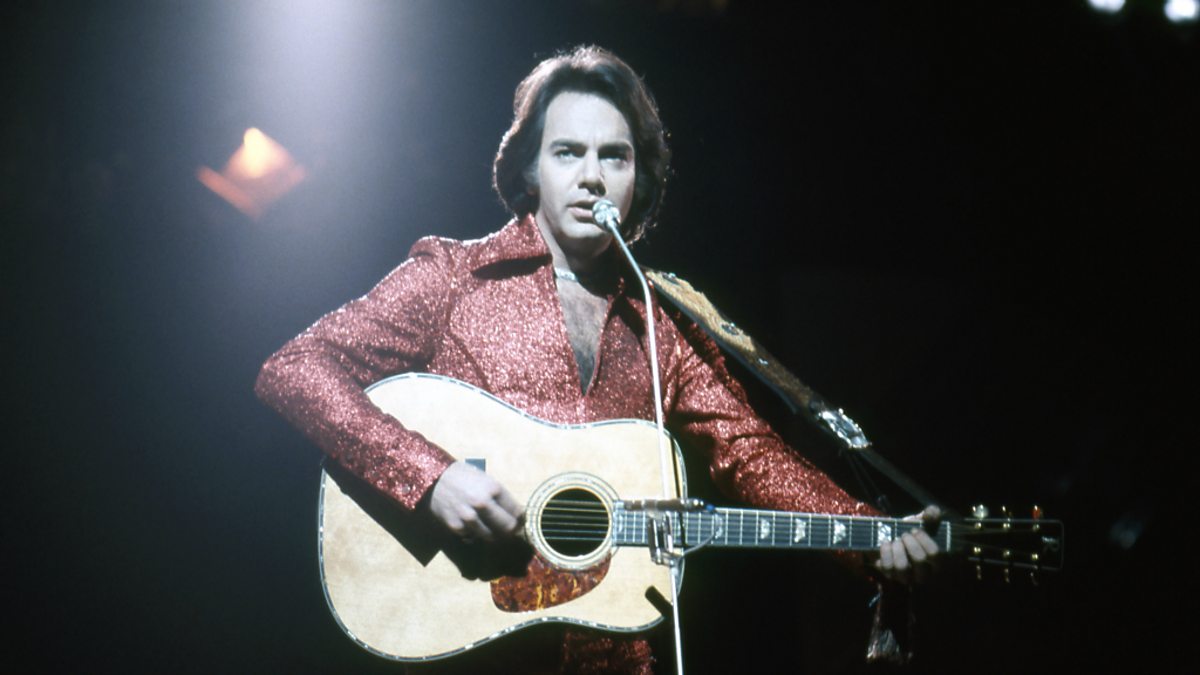

The record’s home base was Diamond’s album Moods, released in 1972 on Uni—an album that reached No. 5 on the Billboard 200 and helped define the elegant, dramatic “grown-up pop” sound that would become his signature. “Play Me” was written by Neil Diamond, produced by Tom Catalano, and (according to widely cited session notes) recorded in February 1972 in Los Angeles—that early-’70s moment when the studio itself could feel like a dim room lit by warm lamps and late decisions.

What makes “Play Me” so enduring isn’t only its chart climb; it’s the way it sounds like it’s leaning closer with every line. Musically, it moves in a 3/4 waltz feel—a gentle sway that immediately suggests intimacy, not spectacle. The arrangement is built to cradle the vocal rather than compete with it, and the song’s famous metaphor is as simple as it is disarming: you are the sun, I am the moon… you are the words, I am the tune. Diamond doesn’t just compare lovers to music—he turns love into a performance where both partners are necessary. One without the other is silence.

Behind the song is an even more revealing truth about Diamond’s artistry in this era: he was learning how to make desire sound tender rather than flashy. Coming off the success of “Song Sung Blue” and before the grandeur of Hot August Night, Moods sits in that sweet spot where his writing feels both confident and strangely private—like a man who can fill an arena but still prefers, at times, to sing as if it’s only for one person. “Play Me” is the clearest example: it’s an invitation, yes, but it’s also a request to be understood, handled carefully, “played” with attention rather than force.

And then there’s the lyric that has followed the song like a mischievous shadow: “song she sang to me, song she brang to me.” The line has been teased, criticized, defended, and oddly cherished—proof that Diamond’s writing often aimed for emotional immediacy over grammatical perfection. In a way, that rough edge makes the song feel more human. Love, after all, rarely speaks in perfect sentences. It speaks in impulses—half poetry, half need.

The meaning of “Play Me” deepens with time. On first listen, it can feel like pure romance: the singer offering himself as an instrument, asking to be brought to life by another. But beneath the sweetness is something more vulnerable: the fear of being left untouched, unchosen, unheard. To ask someone to “play” you is to admit you cannot make music alone—not the kind you want, not the kind that lasts.

That’s why “Play Me” has remained one of Diamond’s most “felt” songs in concert lore: it isn’t a narrative about a character out in the world; it’s a direct address, a candle held up in the dark. You don’t simply listen to it—you recognize it. Because most of us, if we’re honest, have wanted to be more than admired from a distance. We’ve wanted to be held, understood, answered—like a melody finally finding the right hands.

In the end, Neil Diamond’s “Play Me” doesn’t pretend love is clean or clever. It offers something older and rarer: devotion spoken plainly, set to a slow waltz, and left on the turntable like a quiet promise that the heart—no matter how many times it’s been set down—still wants to sing.