“Monday, Monday” is a small pop tragedy dressed in sunshine—because some Mondays don’t just start the week; they end a love, without warning.

First, a quick correction that actually makes the story richer: “Monday, Monday” is originally a 1966 hit by The Mamas & the Papas, written by John Phillips and produced by Lou Adler—and it became the group’s only No. 1 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100, with its peak chart date May 7, 1966. It was released in March 1966, recorded at United Western in Los Angeles, and sung with lead vocal by Denny Doherty—that unmistakable, aching warmth behind the harmonies.

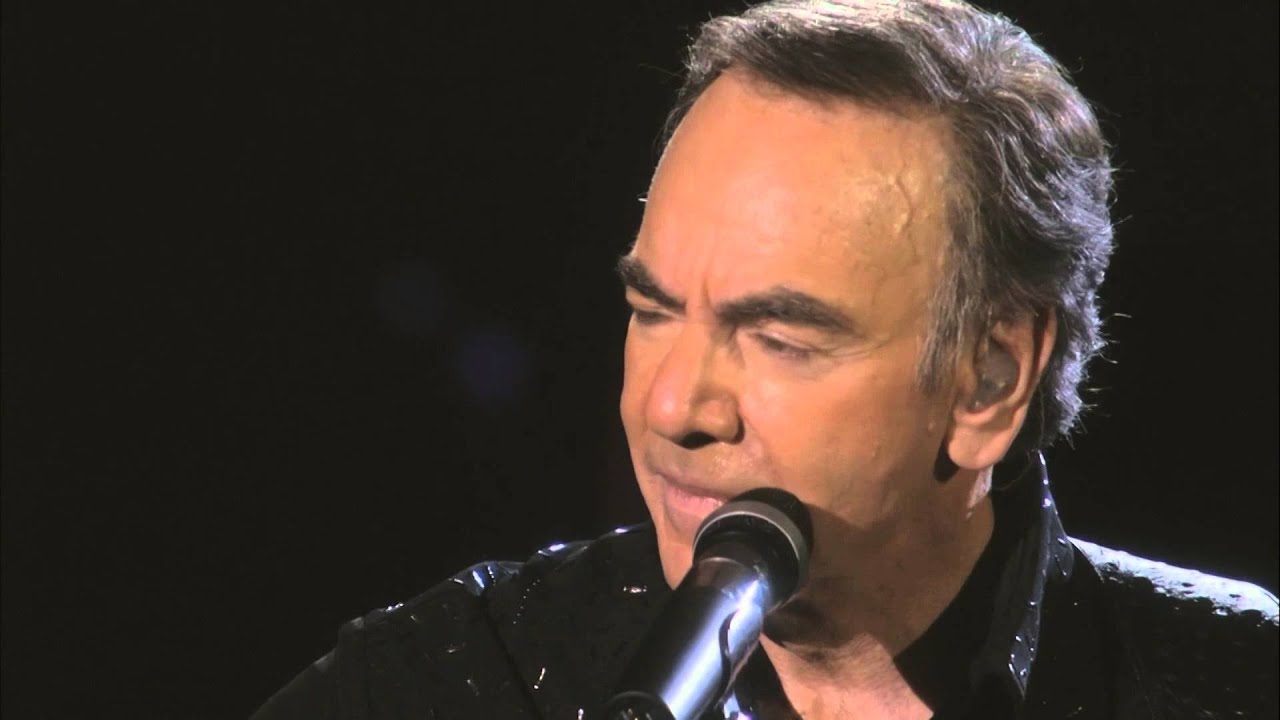

But you asked for Neil Diamond, and you’re not wrong to connect him to this song—because Neil Diamond did record a cover of “Monday, Monday” during his early Bang Records era. It appears on his debut album The Feel of Neil Diamond, released August 12, 1966, where Diamond—still emerging from the Brill Building world—was cutting lean pop records that mixed his own originals with contemporary covers. That album reached No. 137 on the U.S. album chart (as documented in his discography listings). So, in “ranking at launch” terms: the song had already conquered the world in the hands of The Mamas & the Papas, and Diamond’s version arrived a few months later as part of an early-career album statement rather than as a chart-driving single.

Knowing both versions makes the emotion hit harder, because “Monday, Monday” is one of those rare pop songs that hides its bruise inside a bright coat. The lyric is deceptively ordinary: the singer can’t trust Mondays, because the one he loved walked away on that day—“Monday mornin’, you gave me no warnin’…” It’s almost embarrassingly simple, like something you might mutter to yourself while staring at a calendar. And that’s why it lasts. Heartbreak often isn’t poetic when it happens; it’s practical. It interrupts your routine. It makes a day of the week feel like a personal enemy.

Part of the song’s magic is structural—how it behaves like a thought you can’t stop circling. John Phillips reportedly wrote it quickly (he famously said it took about 20 minutes), and the record plays like that kind of sudden inspiration: direct, inevitable, as if it always existed and someone finally wrote it down. It also has that delicious, suspenseful trick—a held breath before the ending, then a key change (modulating up a semitone) that makes the final stretch feel like the heart lifting itself up by sheer willpower. The Wrecking Crew musicians helped build that polished West Coast glow underneath the vocals, giving it the kind of professionalism that makes even sadness sound radio-ready.

So where does Neil Diamond fit into this picture?

In 1966, Diamond wasn’t yet the stadium-poet of later decades. He was a young songwriter-singer on Bang, learning how to present himself on record—often in quick, efficient takes, often surrounded by the pop vocabulary of the moment. Covering “Monday, Monday” made perfect sense: it was a brand-new classic, already proven in the charts, already lodged in the public ear. But Diamond’s voice naturally changes the emotional temperature. Where The Mamas & the Papas wrap the pain in communal harmony—like friends gathering around a hurt—Diamond sings from a more solitary place. His early vocal style has that straight-ahead, street-corner sincerity: less kaleidoscope, more direct gaze. It turns the song into something closer to a private diary entry.

And that’s the deeper meaning of “Monday, Monday”, whether you hear the famous original or Diamond’s early cover: it’s not really about a weekday. It’s about the moment you realize the world can change on an ordinary morning. A relationship can end between coffee and the front door. One sentence can re-color your entire calendar. After that, even “normal” time feels suspicious—because you’ve learned how quickly it can betray you.

That’s why the song still feels strangely modern. We keep looking for patterns to protect ourselves—lucky days, cursed days, routines that promise stability. “Monday, Monday” gently mocks that instinct while sympathizing with it: yes, it’s irrational to blame a day of the week; no, you can’t help it, because memory is irrational. It pins grief to whatever it can hold.

So if you’re listening with Neil Diamond in mind, hear his version as an early glimpse of something he would later master: taking a well-known sentiment and making it feel personally addressed. The big chart glory belongs to The Mamas & the Papas—No. 1 in America, and a record that became their signature Monday blues. But Diamond’s cover belongs to another kind of legacy—the kind where a young artist, still becoming himself, reaches for a song everyone already knows… and sings it as if he’s trying to understand his own heartbreak in real time.