“Tearin’ Up the Country” feels like a last burst of daylight—CCR still moving, still loud, even as the band’s story was quietly running out of road.

The first important fact to hold close is where this song lives in the Creedence timeline: “Tearin’ Up the Country” appears on Creedence Clearwater Revival’s final studio album, Mardi Gras, released on April 11, 1972 by Fantasy Records. The album entered the Billboard 200 on April 29, 1972 at No. 63, climbed to a peak of No. 12, and ultimately spent 24 weeks on the chart—commercially solid, even if the mood around it was anything but celebratory. (In Germany, it charted too—entering May 15, 1972 and peaking at No. 10.)

Now, the song itself: “Tearin’ Up the Country” runs a brisk 2:15, and—crucially—it isn’t a John Fogerty performance in the way most people instinctively expect from CCR. It was written and sung by drummer Doug Clifford, and it’s placed early on the record (track 4), like a little flag planted in new territory. That detail is not trivia; it’s the entire atmosphere.

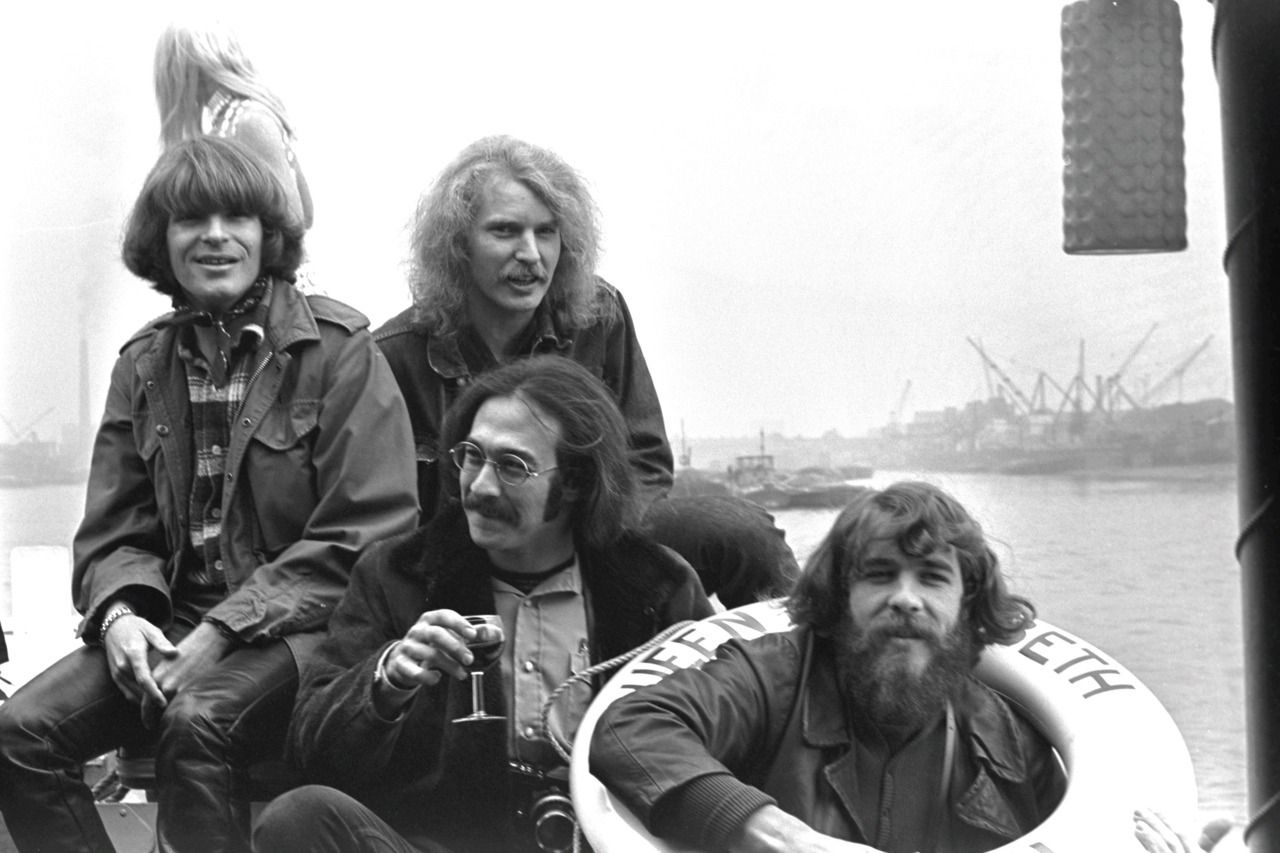

Because Mardi Gras was born out of a band trying to survive its own fractures. After Tom Fogerty left, CCR continued as a trio, and the next album followed a “democratic” plan where the remaining members shared writing and lead vocals rather than relying solely on John. The sessions were marked by personal and creative tensions, and CCR disbanded later in 1972, not long after the album’s brief tour.

So when you listen to “Tearin’ Up the Country,” you’re not just hearing a song—you’re hearing a band’s inner argument turned into music. It has that familiar Creedence engine—short, punchy, made to roll down a two-lane highway with the window cracked. Yet the voice is different, the center of gravity shifted. Clifford doesn’t sing like Fogerty, and he doesn’t need to. Instead, he leans into a workingman’s directness: the pleasure of movement, the simple rush of going fast enough that yesterday can’t grab your coat.

That’s the emotional meaning hiding inside the title phrase. “Tearin’ up the country” can sound reckless, but it can also sound like necessity—like someone who has to keep moving because standing still means thinking too hard. In the context of Mardi Gras, the song becomes almost symbolic: a burst of momentum from a band that, behind the scenes, was losing its shared compass. You can feel how the track wants to be uncomplicated fun—music as escape, as muscle memory—while history insists on being complicated anyway.

There’s also a tenderness in how unpretentious it is. No grand sermon, no myth-making. Just a quick shot of kinetic life, delivered by the drummer—usually the heartbeat in the back—stepping forward to say, in effect, I’m here too. That alone makes the track poignant. Not because it is CCR’s greatest composition, but because it is CCR trying, one last time, to be a band rather than a single voice with three shadows.

Even the album’s label-side commentary frames it this way: Concord’s album notes explicitly highlight Doug Clifford “notably” in “Tearin’ Up the Country,” as part of the record’s unusual sharing of the spotlight. Concord

And when the song ends—quickly, almost abruptly—you’re left with that strange, unmistakable feeling that comes with endings you don’t notice until they’re already gone. A car disappears down the road. The dust settles. The countryside is still there… but the sound that tore through it will never quite return in the same shape again.