“Anthem” is the sound of a restless spirit choosing flight—an inward vow to rise above limitation, even when the world below insists you stay small.

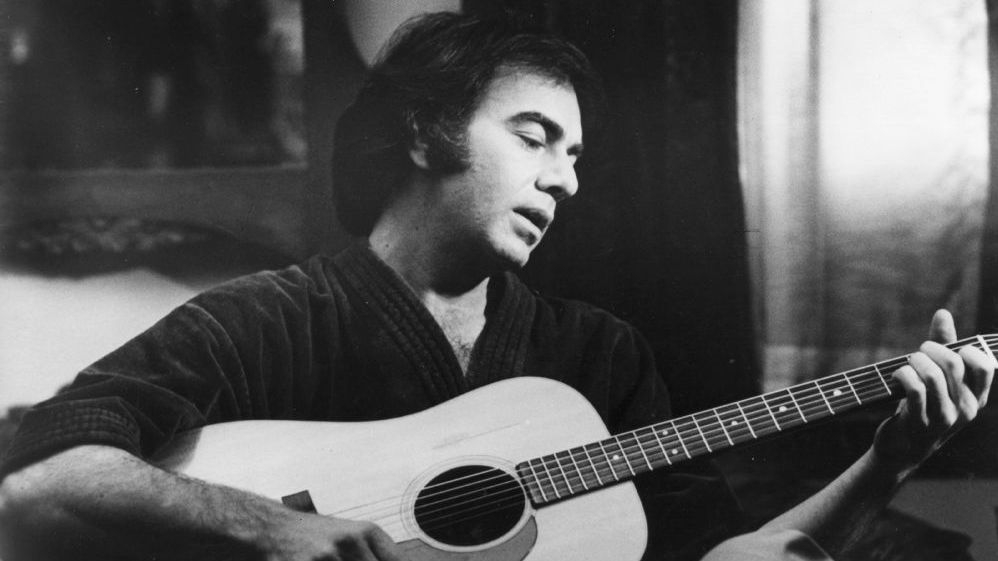

When Neil Diamond released “Anthem” in 1973, it arrived not as a conventional radio “single moment,” but as part of something rarer in his catalog: a full cinematic score-song cycle for the film Jonathan Livingston Seagull. The track sits inside the Jonathan Livingston Seagull (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack), issued by Columbia on October 19, 1973, with Diamond credited for music and lyrics and longtime collaborator Tom Catalano producing.

If you measure “arrival” by chart thunder, “Anthem” is quietly unconventional. In Germany’s official chart database, it appears as a release entry for 1973, but without the “chart entry / peak” data you see for Diamond’s charting singles—strongly implying it did not register an official chart run there. In the United States, the larger story is the album itself: Jonathan Livingston Seagull became a major commercial success and reached No. 2 on the Billboard 200—famously, the closest Diamond came to a No. 1 album until decades later.

And that context matters, because “Anthem” isn’t built like a hit single engineered for the jukebox. It’s built like a statement—three minutes that feel like a wide horizon. In the soundtrack’s architecture, it functions as a cresting emotional summit: a song that carries the film’s central idea (aspiration, self-transcendence, the ache of being different) and turns it into a human declaration. The film, adapted from Richard Bach’s novella, follows a seabird cast out by his flock as he tries to break the limits of flight; Diamond’s music is, in many ways, the film’s speaking voice.

The “behind-the-scenes” story has its own bruised poetry. The production became contentious enough that legal action entered the picture, and a judge ordered minutes of Diamond’s score and several songs—explicitly including “Anthem”—to be reinstated, with credits specifying “Music and songs by Neil Diamond,” plus acknowledgment of Lee Holdridge in the background score adaptation and Tom Catalano in music supervision. Diamond later said the experience made him vow not to get involved with a movie again unless he had complete control—an artist’s way of admitting how personal this music had become.

Musically, “Anthem” sits at the meeting point between Diamond the pop songwriter and Diamond the cinematic storyteller. The Seagull soundtrack is known for lush orchestration (Holdridge’s role is central), and its personnel even includes a credited boys’ choir—details that hint at why the record can feel almost liturgical in its uplift. You can hear that “score” thinking in “Anthem”: the way the melody seems to look outward, the way the arrangement doesn’t merely accompany the voice but surrounds it, like wind and sky made audible.

So what does “Anthem” mean? It’s not patriotism in the usual sense; it’s allegiance to a private truth. An anthem, here, is a promise you make when nobody is applauding—when the cost of becoming yourself is loneliness, misunderstanding, or starting again from the margins. That’s why the song still resonates: it treats yearning as something dignified, even sacred. It insists that striving is not vanity but vocation.

There’s one more irony—gentle, and somehow fitting. The film itself struggled critically and commercially, yet Diamond’s soundtrack outlived it in public affection and acclaim, winning major honors for its score. In a way, “Anthem” became what its title suggests: not the banner of a movie, but the banner of an inner life—quiet, persistent, and determined to keep flying.